TMW #168: Who moderates the content moderators?

Welcome to The Martech Weekly, where every week I review some of the most interesting ideas, research, and latest news. I look to where the industry is going and what you should be paying attention to.

👋 Get TMW every Sunday

TMW is the fastest and easiest way to stay ahead of the Martech industry. Sign up to get TMW newsletters, along with a once-a-month complimentary Sunday Deep Dive. Learn more here.

Editor’s note: I am thrilled to bring you TMW Researcher Keanu Taylor’s first Sunday Essay. After almost four long years of bringing TMW essays to you week on week, for the first time, you’re reading our weekly deep dive analysis from someone other than me. Keanu’s intellectual prowess and industry insight has been growing now for almost 6 months, and I can promise you that what he has to say will resonate, challenge and inspire. Please welcome Keanu to the Sunday Deep Dive driver’s seat! Learn more about Keanu.

Juan Mendoza, CEO and Editor

Who moderates the content moderators?

Advertisers can change the internet for the better.

I have a confession. I only watched the movie Jaws for the first time last year. Yes, I know it’s a classic and it turned Steven Spielberg into a household name, but it was released nearly 20 years before I was born, so cut me some slack. There is so much tension throughout the movie whenever a murky shadow appears in the water that it is easy to forget that the real bad guy is not a shark, but Mayor Vaughn, who ignores safety advice and mounting evidence of danger so that he can keep the crowds coming in, the beach vendors happy, and the dollar circulating.

Much like Amity Island before the shark attacks, the early open internet was idyllic. It completely revolutionized access to information, birthed new ways of consuming media and connecting with family, friends and even strangers, and created jobs and prosperity for millions of people. It gave us opportunities that we’d never dreamed of.

And it was, and still is, primarily powered by ads. It doesn’t matter if it is search, social, display or anything else: Ads make the digital world go round. Ads also made a small number of companies exceedingly powerful. These companies arrange the content, the content brings the eyeballs, the eyeballs bring the advertisers, and the advertisers bring the moolah.

Over time, the initial promise of the internet has been eclipsed by murky shadows swimming amongst the ever-expanding stream of content. At first it was one shark, then two; now it’s a shiver of sharks, and they’ve got their fins well out of the water.

Sharks in the water

What was your first memory of the early internet? For me, it was getting home from school and logging on to Myspace. Back then, the only problem I had with the internet was who to put in my top friends list, and what to do when someone interrupted me messaging friends on MSN by using the dial-up.

Snapping back to the present day, social media companies have come under increasing scrutiny for the content on their platforms. Myriad problems have been raised over the years: children being exposed to Child Sex Abuse Material (CSAM), increasing suicide rates amongst young people, election interference, promoting ethnic cleansing, polarising political discourse, spreading misinformation, and invasion of privacy – not to mention startling links to poor sleep quality, fertility rates, and even obesity.

And it’s not just the social media platforms that have content moderation problems: it also applies to search engines. Search engines don’t have to moderate content to the degree that social media companies do, but they do rank content and moderate where search ads appear next to that content. And when I say search, I really mean Google Search, which became the top search product in late 2002 and never looked back, now holding 92% market share globally. Since then, that monopolistic power has introduced bad incentives that have led to even worse outcomes for society, including anticompetitive behavior with competing products, slowly killing off news media, and mass content theft for AI training.

Similarly to Search, while the Adtech platforms that underpin programmatic advertising don’t directly moderate the content of sites where they show ads, they must moderate where ads are displayed to ensure the content is brand-safe and brand-suitable for advertisers. When Google bought DoubleClick in 2008 and expanded the use of third-party cookies (3PCs) to programmatic display advertising, it accelerated an Adtech industrial complex that enabled fraud, mass invasion of privacy, and questionable advertising practices such as targeting gambling addicts.

The modern internet is chock-full of platforms that moderate content in ways that create a slew of negative externalities. Who’s moderating the moderators?

It was the Law of the Sea, they said.

Well, the obvious answer is regulators. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that regulators are getting serious on the issues that content moderators have caused, but regulation has come years – maybe decades – late and is yet to fully bite, especially in the case of social media.

In February, the US Senate held a congressional hearing taking aim at Meta, TikTok, Discord, Snap, and X over child safety concerns, which was a microcosm for the US’s social media regulation, where there have been 40 congressional hearings since 2017, but no new laws passed.

Concern over the content on these platforms isn’t just limited to the US: the EU is a couple of steps ahead with regulating content on social media. As part of the Digital Services Act, the EU is levying a tax on the Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) in the social media space that will be used to support enforcement of content moderation laws. Predictably, the big social players have been desperate to avoid this, with TikTok and Meta both challenging their respective designations as VLOPs in court.

The regulatory pressure isn’t just coming from new laws, but also old ones. In TMW #165, I covered the US Supreme Court case, which heard arguments about laws from Texas and Florida that, under the auspices of the First Amendment right to free speech, sought to limit social media platforms’ ability to moderate political content that they deem to be objectionable. NetChoice, representing the usual social behemoth suspects, fought tooth and nail in a marathon four-hour hearing, and with good reason: Taking away any content moderation power would be a massive risk for the social giants as it compromises their ability to maintain brand safety for advertisers.

But it's not just in the courts of law that social platforms are fighting to keep control over content moderation; it’s also in the court of public opinion. The prevailing theory of regulators during the early days of the internet was one of self-regulation: These massively powerful tech companies will regulate themselves because… yeah, who knows why they thought that would work. And it seems that social media companies have since guzzled down that Kool-Aid as they have gone about setting up oversight boards that are meant to convince the public that self-regulation is a viable option.

Only problem? Those oversight boards are as toothless as newborns. Meta, the single most significant social media company our little blue dot has ever seen, has been operating since 2008, yet they only set up their oversight board three and a half years ago. The board examines singular, high-impact posts on Facebook and Instagram to determine what types of content should be allowed or not. The ruling applied to the particular post used as evidence is binding, but applying it to similar content is not. In one case, it took the board five months to issue a ruling on a post calling for the death of Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei. So, it’s toothless and slow.

Similarly to social media, regulation has arrived very late in the day for Google Search. The US is looking backwards at the history of Google’s search monopoly in its antitrust case, and the EU is looking forwards by implementing regulation that will change how ‘gatekeeper’ platforms have to behave in the future. Both approaches are fraught with challenges and risks.

The US antitrust case investigating Google Search paying Apple 36% of Safari-generated search revenue in exchange for being the default browser on Safari sounds damning, and it may very well lead to a mammoth fine. But the problem is that for it to truly have an impact on Google, it would have to be one of the largest corporate fines in history. Even if that did happen, these things take years to land; Google is still appealing the EU’s fine for the antitrust case they launched back in 2017. The bigger risk here is what happens if Google isn’t found guilty; this could solidify Search’s impunity and encourage more anti-competitive, monopolistic behavior in the future.

As I explained in TMW #166, the EU’s Digital Markets Act is a step in the right direction toward breaking up Google’s search supremacy. The reality is, however, that Google’s plans to comply by implementing choice screens and allowing users to uninstall Chrome on its devices puts too much cognitive load on consumers to have an immediate impact.

But the buck doesn’t stop there: Programmatic advertising has also been targeted by regulators, with the UK’s Digital Markets Authority intervening to stop Google’s 3PC deprecation plans for fear that Google will use them as a means to further entrench its dominance in display advertising.

Regulators have certainly woken from their self-regulation daydream and are now being very active in dealing with Big Tech, but they gave the dominant platforms a massive head start that is proving hard to claw back.

Hark now, hear the sailors cry.

Despite the limited progress from regulators and the companies themselves, there is an obvious playbook for undermining the power of social media platforms that won’t put societal safety first in their regulation of content and it is typified by the plight of Twitter, now infamously X. Upon taking over the blue bird, Elon Musk gutted the content moderation department and committed to a “Freedom of speech, not reach” policy that meant users could post deplorable content, scams and hate speech without facing the risk of removal.

Advertisers didn’t like this one bit. Brand safety on X became a serious concern almost overnight, leading to a mass exodus of advertisers from the platform in December 2023. X even lost its Trustworthy Accountability Group brand-safe certification. Where a normal CEO might have tried to allay the concerns of advertisers, Musk said to them: “Go fuck yourself”. Bold.

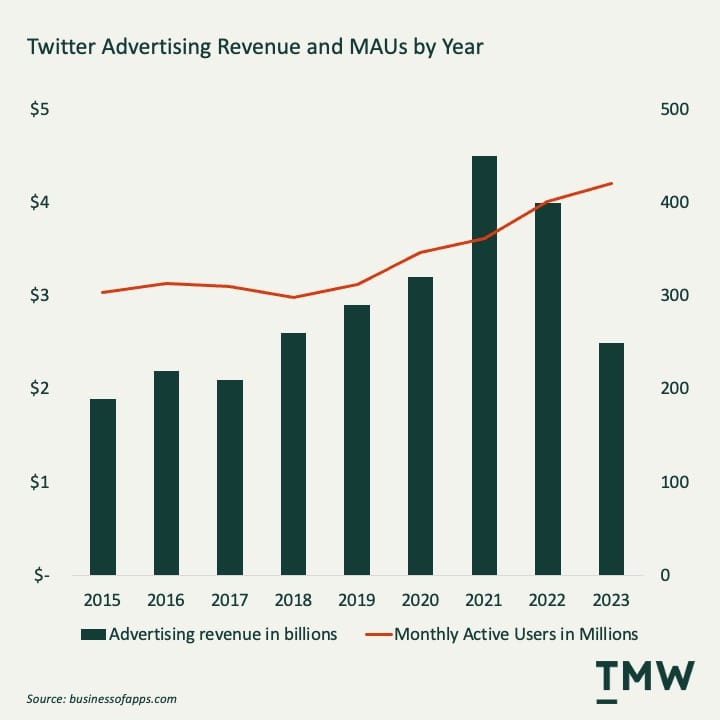

Even before Musk took aim at the advertisers that publicly pulled their advertising off X, the company’s ad revenue was tumbling, although monthly active users have been stickier than you might expect, mainly driven by growth outside the US.

Although advertisers pulling out of X hasn’t changed Musk’s light-touch content moderation policies, it has massively impacted the financial health of the business and opened the door for competitors to come in and steal users: Threads, for example, has already reached 130M MUAs. Over time, as the ad dollars inevitably continue to dry up for X, the platform will continue to lose its relevance and reach – ergo, the scale of harm it can do to society. That, or Musk will sell it to someone who recognizes the importance of brand safety to advertisers and starts cleaning up the dog’s breakfast that’s been left behind.

Google’s dominance in search has also led to complacency towards the needs of its financiers. In TMW #155, I covered a report released by the online ad transparency tech platform Adalytics, which attacked Google’s lack of transparency around its Google Search Partners program. The report estimated that 6-8% of sites in the program are not safe for brands (e.g. pornography, bestiality, fringe political commentary), even though Google opts in advertisers by default and provides little transparency as to where ads are being placed. With AI threatening to change how the industry works, now is definitely the right time to be questioning Search’s dominance.

In TMW #167, I covered another report by Adalytics which called out a who’s who of DSPs, ad verification and measurement platforms, major agencies, and even trade media for misleading claims about the extent to which they had dealt with the scourge of Made For Advertising sites. This report was a follow-on from a detailed study undertaken by the ANA that exposed the lack of transparency in the programmatic media supply chain and how much advertising money goes to waste.

The scale of reaction of the marketing industry in response to Twitter’s demise and these reports prove two things: One, companies like the ANA, Adalytics, the IAB, and others holding the industry to account are crucial for transparency; and two, advertisers can mobilize around a common problem when they are well informed.

Casting the net wider

I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking that each advertiser is just a drop in the ocean, and how can you possibly make a difference? You’re justified to think that. No single advertiser alone can force the social media giants, Google Search, and the Adtech industrial complex to moderate the content they host, rank, or serve ads on to iron out negative externalities. But advertisers make the open internet go round, and therefore, they have the power to make the digital world a better place. And it all starts with a change of definition.

The IAB defines brand safety and brand suitability as such:

Brand safety is avoiding unsafe advertising environments to protect brand reputation.

Brand suitability builds on brand safety by displaying advertising in the right environments to the right audience.

So, brand safety is about not offending consumers, and brand suitability is about relevance. Sure, those are worthwhile goals, but they don’t go nearly far enough.

Imagine if PETA decided to advertise an anti-animal cruelty fundraising drive by painting an ad on the side of a cow. There’s nothing offensive about a cow in a paddock, and the ad is ostensibly about animals, so it passes the brand safety and suitability checks. The problem with that scenario isn’t causing offense or a lack of relevance – it’s the negative externalities of the method of delivery.

We need to broaden the criteria through which we assess the suitability of different digital advertising options to encompass how the brand is delivered. I propose that we call it brand delivery, and define it as such:

Brand delivery builds on brand safety and suitability by considering the externalities of the delivery platform or method, allowing advertisers to avoid advertising in ways that lead to bad outcomes for society at large.

Am I being overly idealistic? Maybe. But now is the time for advertisers to start building this into their planning. AI and belated – yet significant – regulation mean that the status quo of the digital ecosystem is being put under increasing pressure, and the dominant players and systems may become increasingly off balance. Advertisers being more selective about where they advertise would only add to that.

Going back to Jaws, the heroes of the movie end up being Chief Brody, Hooper and Quint, who sail out to kill the Great White shark. Of course, a Hollywood movie needs a hero, but Quint didn’t have to sacrifice himself to become one. He could have tried to convince the vendors selling sunscreen and ice-creams by the beach that they were inadvertently putting people’s lives at risk. After all, Mayor Vaughn only kept the beaches open to keep the dollars rolling into the vendors so he could take his cut in tax.

Advertisers are the ultimate content moderators. With plenty of help from regulators and AI, they can be the heroes to change the internet for the better.

🔓 Are you ready to join the PRO's?

Get the entire Wednesday Martech Briefing and all of our newsletters every week with TMW PRO. It's the easiest and fastest way to make sure you're fully informed on how the marketing technology industry is evolving.

Here’s what some of our existing TMW PRO members have to say;

“TWM is a finger on the pulse of what's happening, with the clarity of insight to see the important patterns underneath the noise” – Scott Brinker (VP, Hubspot).

“I recommend TMW to all leaders who are customer-focused and transforming companies via digital technologies” – Kazuki Ohta (CEO, Treasure Data).

“I've subscribed to many Marketing newsletters, but TMW is at the top of my list with the most valuable content for marketing professionals" – Lilly Lou (Marketing Director, Icertis).

TMW PRO is an invaluable resource that’ll help you to truly transform and future-proof your career in Martech.

Are you ready to join the PRO's?

If the answer is yes, CLICK HERE.

Stay Curious,

Make sense of marketing technology.

Sign up now to get TMW delivered to your inbox every Sunday evening plus an invite to the slack community.

Want to share something interesting or be featured in The Martech Weekly? Drop me a line at juan@themartechweekly.com.