TMW #113 | Abandoning the Metaverse

Welcome to The Martech Weekly, where every week I review some of the most interesting ideas, research, and latest news. I look to where the industry is going and what you should be paying attention to.

👋 Get TMW every Sunday

TMW is the fastest and easiest way to stay ahead of the Martech industry. Sign up to get the full version delivered every Sunday for this and every TMW, along with an invite to the TMW community. Learn more here.

Last year I curiously wandered into a VIP area hosted by Meta at a tech expo. I sat down, put on the Oculus VR headset, and gave their Metaverse demo a good go. I was teleported into a generic and sterile workplace room with a virtual whiteboard. It was the kind of room you’d expect to see in Meta’s Menlo Park HQ – modern, but nondescript, bland and kind of lifeless.

As I started exploring, I felt two things. The first was disorientation; I couldn’t help but feel like I was going to trip into someone in the real world. The second was, how can I say this… extreme boredom. Meta purchased a very expensive VIP booth, and paid for a sizable team to staff it, to show me this?

Afterward, I proceeded to ask the Meta staff what drew them to the company. Their answer? The money was really good. No one I talked to was there to help usher us into Mark Zuckerberg’s vision for the Metaverse.

In 2021, when Zuckerberg changed the name of the company to Meta, he proudly announced that “we’re going to be Metaverse first, not Facebook first.”

It’s now 2023, and the whole idea of the metaverse seems to have been plucked clean out of the stream of internet history. The hype has subsided, companies are now investing elsewhere, and journalists at the Financial Times are asking questions like what happened to the metaverse? And for good reason.

In 2022 alone, investments across mergers and acquisitions, venture capital, and private equity reached more than $100 billion. As the category set into its own season of hype, companies of all shapes and sizes pivoted to make good use of where the capital was flowing. Over 2021 and 2022, that was the metaverse.

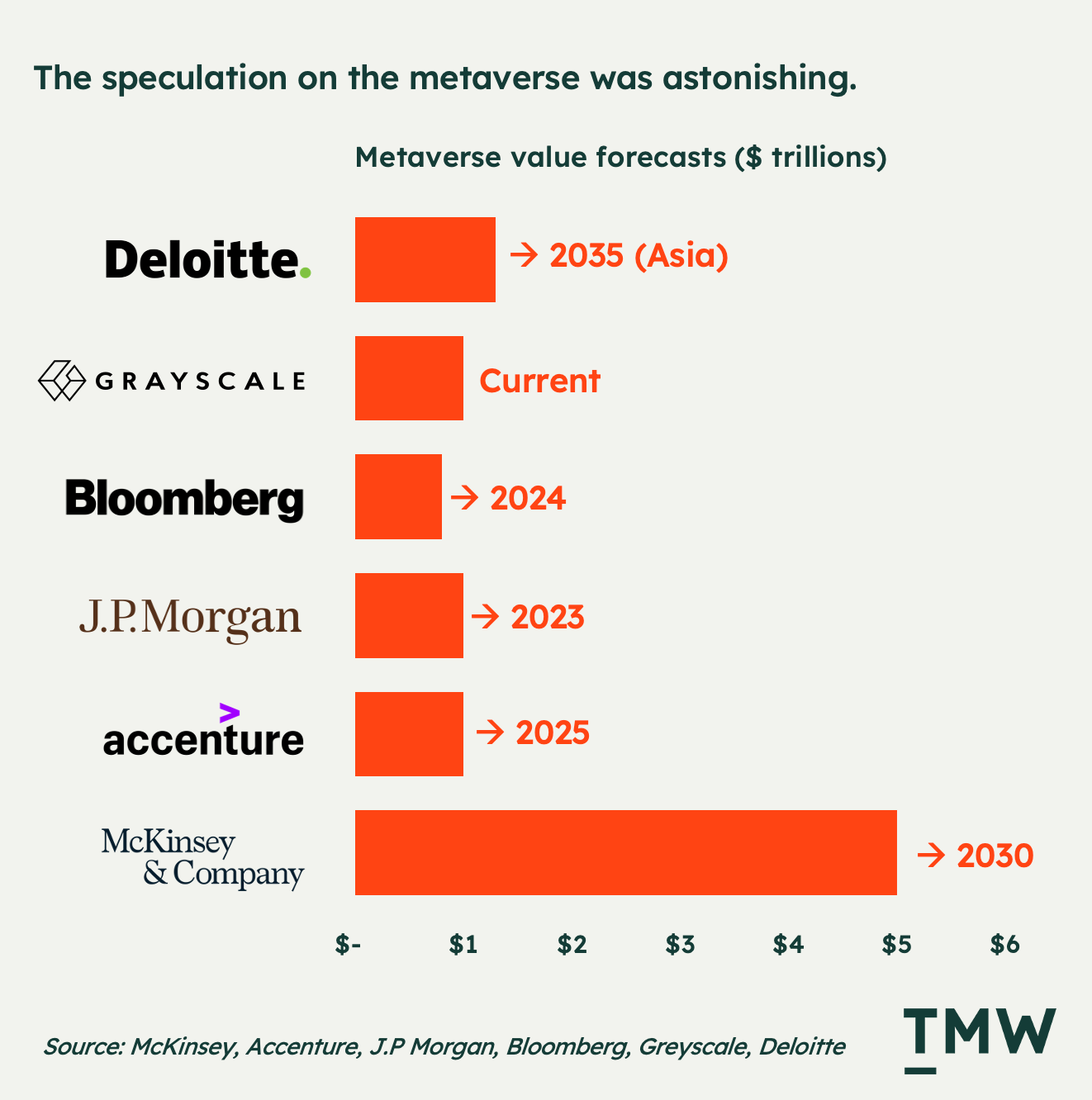

But it wasn’t only that investing in the metaverse was exorbitant: the world’s major consultancies and research groups were also suggesting that brands shouldn’t be left behind when it comes, offering extremely optimistic forecasts for how much value the metaverse will unlock. Will the metaverse be worth $5 trillion by 2030? Who knows. But it makes a good headline.

Just this past week, Mark Zuckerberg has come out to say that the Metaverse is no longer a major focus of the company and that they are going to become an “AI company” – an obvious capitulation and acceptance of what the tech cycle cares about in 2023. Meanwhile, Microsoft has closed their industrial metaverse team, after only four months, laying off a further 100 staff members.

As the companies that set the Metaverse trend now move away from it, and investors and consulting firms try to adjust their optimism for an overhyped category, it is worthwhile thinking about how the metaverse came to be and why everyone is abandoning the idea of it.

What were the goals of the people who were promoting this stuff? And did it make any big difference to how marketers approach these new experiences? Or are we looking at an example of the world’s most overhyped vaporware? Let’s explore the most expensive forgetting in the history of the web.

A branding breakthrough

Could the Metaverse have been a strategic smokescreen and branding pivot to recover the integrity of Facebook? It certainly is vague enough to be. If we take ourselves back to 2020, the idea of a metaverse was not on the radar of almost everyone.

There was an idea expressed through Neal Stephenson’s 1992 book Snow Crash that became the necessary pretext for late 2021, when Mark Zuckerberg announced a major rebrand to Meta, with a “what if” video explaining what the Metaverse would look and feel like. And with that, the company kind of created a category out of thin air. It was a bold new direction, a new way of thinking about how we work, create, shop, and socialize on the internet.

The very idea of the Metaverse not being a technology category, a new company, a new invention or even a social media platform was the brilliant move Facebook made when they made their Meta-morphosis. Instead, Zuckerberg said himself that the Metaverse will be the next big shift in technological connectivity:

“We believe the Metaverse will be the successor to the mobile internet. We’ll be able to feel present like we’re right there with people no matter how far apart we actually are. We’ll be able to express ourselves in new, joyful, completely immersive ways and that’s to unlock a lot of amazing new experiences.”

However, the pivot to Meta became a way to force a conversation about the troubled Facebook into something else. The company found itself in the middle of several damaging brand and consumer situations with Cambridge Analytica, the growing distrust of the brand on privacy grounds, declining youth adoption of Meta’s apps, and the increasing malaise of genocides, teenage depression, and isolationism that Facebook’s family of apps played a role in.

This branding move towards the Metaverse was successful in that it changed a conversation about Facebook from a large enterprise company on the decline and losing touch in the face of new competitors like TikTok, to a courageous new direction with a, $10 billion bet to reorient the company towards virtual worlds similarly to how Facebook pivoted to mobile as smartphones grew in prevalence.

And it kind of worked.

The shift to the metaverse has cost Meta almost $25 billion since the rebrand, while only making $2.2 billion in 2022 from metaverse products. This means the company has a long way to go to replace its social media ad-monetization model. But with this new shift, even with a change of focus in 2023 into other areas of the business, the company has done an overall good job at invigorating the brand and steering conversation away from most of its other problems, for now.

Was it worth the money? For Meta, with an increasingly hostile public perception, it probably was. This raises the question: maybe the metaverse wasn’t really a whole new technological movement, but a PR and brand marketing smoke-and-mirrors operation during a hype-fueled pandemic tech bubble?

One of the main reasons why I think this is the case is that the metaverse wasn’t like the launch of the iPhone or the PC in times past – those products showed the tangible and practical ways they will help people do things better with real hardware and software. Meta was not like most successful product launches.

Zuckerberg on the other hand launched Meta with a vision for the future, backed by some 3D animation and interesting ideas. It was like the entire thing was based on speculating on a far-flung future, with abstract and vague concepts – a pitch for something. But something we cannot touch and feel today. Which creates its own kind of problems.

Category confusion

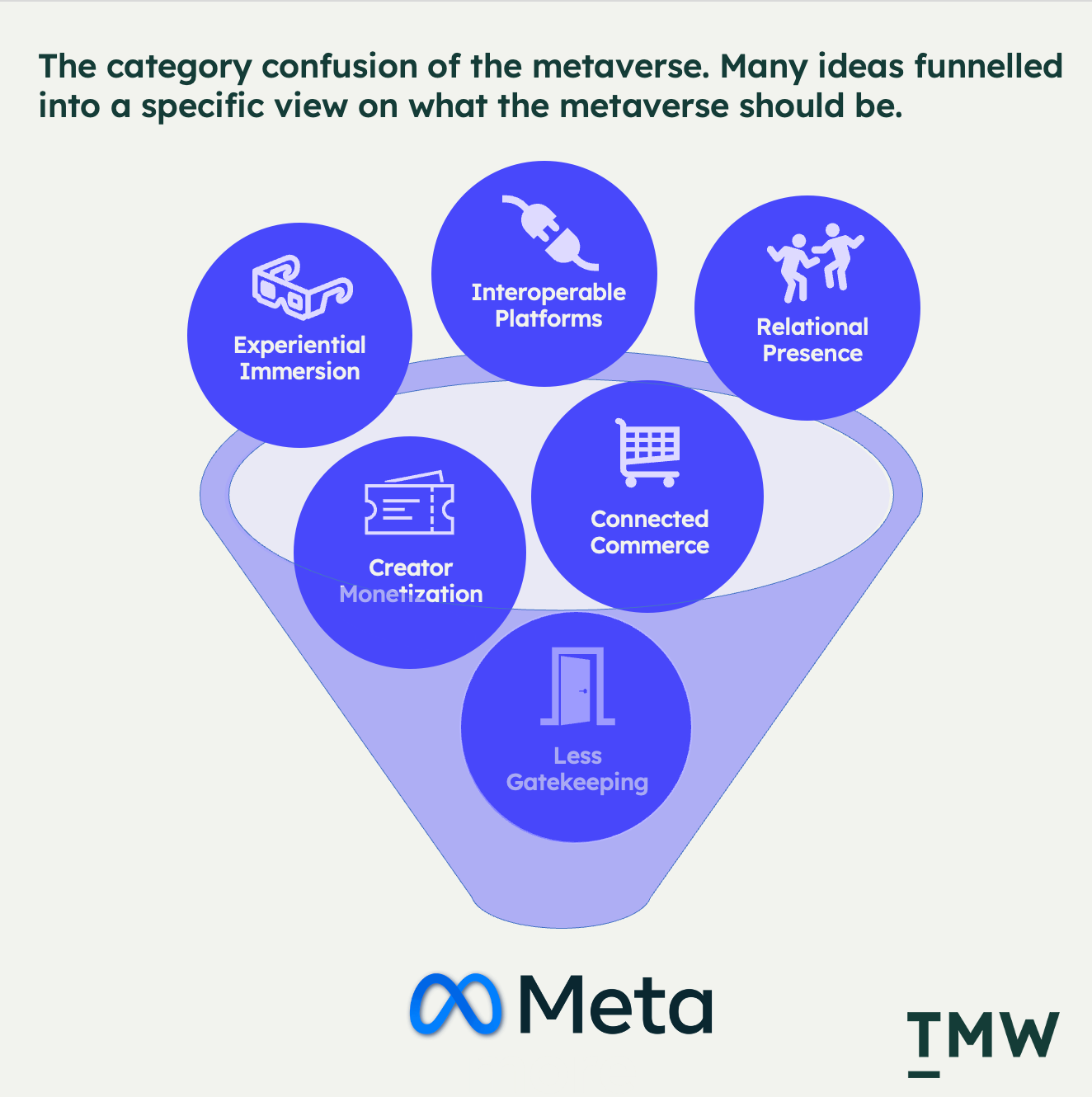

No one knows what the metaverse truly was. And that’s a big reason as to why the category hasn’t been able to find staying power. What Meta attempted was to bring a number of interconnected ideas together under the concept of the Metaverse. From connected commerce to relational presence and immersive experience, the vision was big, but it was blurry and eventually became too confusing and bewildering for anyone to comprehend fully.

Part of the reason for this is how it coincided with the Web3 hype cycle which introduced concepts of decentralization, and distributed ownership to give people freedom from banks and gatekeepers. It appears that the metaverse suffered from being lumped into Web3 because the movement was a product of the times: a pandemic-induced season of isolation that prompted everyone to think about new ideas to do with connecting with others and finding new ways to make money online.

The category is neither a product, business model, or emergent technology. The best way to think about the metaverse is that it was a movement. That movement was driven by a sense of technological optimism for internet innovation, frustration with the current status quo, and the idea that the internet economy was stifling creativity and connection instead of helping people to access better economic opportunities and relationships.

One of the interesting concepts that have come out of this kind of category confusion was the blending of the virtual world with the physical. Zuckerberg called it an “embodiment of the internet”, an enhancement of the existing internet experiences today.

And there’s some truth to this: for a lot of people, their online lives involve experiences, career prospects, and relationships that can only exist online. The deep sense of presence that Zuckerberg was promoting makes some sense, as it has the potential to enhance what we already do on the web to make it more enjoyable and valuable for people. I agree with Marc Andreesen that for many people, the internet is a vastly better place to spend time than the physical world.

But does this mean we should be investing in the virtual over the physical? While for some, the virtual world has more opportunities, it is only made better by making the real world a better place for everyone. The biggest fallacy of the metaverse is the arrogance that people could live fulfilling lives without connection to the physical world. As Dror Poleg explains:

“Humans need to breathe, they need to eat, they need to move around, they need to interact with each other, they need to be safe from physical danger. Their ability to do all these things depends on the quality of their physical environment. VR goggles, immersive games, and live-streamed kisses cannot make up for physical decay.”

Another aspect that became a part of the overall category was the idea of openness and interoperability. Zuckerberg himself suggested that the metaverse will be more open, without the walls of massive social networks, e-commerce, or media platforms. This was a fairly bold suggestion to make – Facebook is the company it is today because it’s a closed ecosystem of data, commerce, and experience.

Again, there is so much vague hand-waving from almost everyone at these ideas and a gaping hole of logic as to why people would want any of this, that it’s no surprise that the idea of the metaverse simply fell out of our discussions. It was too confusing, complex, and dependent on borrowed technologies, pandemic needs, and utopian ideas. For a company like Meta that hasn’t really built anything novel since the newsfeed, and with its revenue almost entirely supported by advertising, you could say that its metaverse ambition was too big, too broad, and too clumsy.

Humbled in the metaverse

This leads us to embarrassment. Like the Web3 movement, the metaverse has also suffered from its own forms of public humiliation and humbling failures from the get-go.

The Meta launch video was so out of touch that most of the serious people in tech derided it for its lack of maturity. It kind of came off as a weird, sort of detached video game demo. Some of the demo even presented preposterous ideas such as sending a holograph of yourself to concerts, which would literally break the laws of physics.

But the thing that really kicked off the public’s dissatisfaction was when Meta started to roll out its VR products for consumers. For a hot new consumer tech trend, it quickly became uncool – the last thing you want when you’re trying to attract the next generation to try your products. Besides the weirdness of not having legs in these virtual worlds, NYT columnist Kevin Roose summed it up well:

“It’s genuinely puzzling that Meta spent more than $10 billion on VR last year and the graphics in its flagship app still look worse than a 2008 Wii game.”

As these ideas started to proliferate in the market, the metaverse became metaverses. Companies that tried to integrate crypto into 3D worlds started selling digital land, and raising millions in venture capital, but shortly after the hype subsided, these companies had a comical lack of traction. The two main platforms tackling both the Web3 and Metaverse were Decentraland and the Sandbox, and after building ecosystems that were valued in the billions, by the middle of 2022, they both had less than 1,000 daily active users.

This kind of failure quickly becomes a warning signal to avoid participation. No marketer wants to launch anything where no one is showing up. And this became a massive issue. The EU government hosted a metaverse party that cost €387K with only 300 attendees. The CMO of Walmart launched their virtual world on Roblox, and his introductory address had only one person in it.

The metaverse concept should be able to exist in an actual economy where businesses buy and sell products or services. But for most companies, there wasn’t that much value to be gained. There’s no infrastructure for advertisers, and costly mistakes and lack of participation means that the metaverse did not meet the expectations that the hype was setting. 2022 was a humbling (and lonely) time in the metaverse.

Post-pandemic realities hit hard

Interest rates are up, inflation is high and there have been warnings of a so-called recession for almost a full year now. All of these things have impacted Meta, but also people’s appetites for experimenting with ideas that are not fully formed, and with questionable value.

That’s why the post-pandemic environment has probably been the biggest death blow to the idea of the metaverse.

As crypto collapsed under its own weight of speculation, crime, and disillusionment, losing $3.9 billion in fraud, there was nowhere else to go. Once the crypto exchanges started to pause withdrawals, and when NFT projects were outed as outright scams, and thanks to the work of Molly White who worked tirelessly to report on the varieties of fraud and mistakes that plagued the industry, this caused regular consumers to become wary of the environment and participation with it.

But it’s not only the economic environment. One of the main concepts of the metaverse was the idea of digital presence, which makes a lot of sense when connecting with co-workers, family, and friends when virtual is the only option. Since the pandemic has subsided, borders are now open, masks are no longer mandatory in most places and people are going back in store, and doing all the normal things people do outside together.

This seems obvious, but it’s powerful. If the metaverse is about presence, then there’s no way you can disrupt the importance of being together in person. Even the stock value of companies that leveraged virtual presence is now in steep decline. Gaming platforms like Roblox, Minecraft, and Fortnight – all companies that were seen as the primitives of the metaverse and enjoyed explosive growth during the pandemic – are now stagnating in user participation.

During the pandemic, the idea of these kinds of platforms would be a big deal became a major narrative. At the time, Roblox was growing rapidly, at one point boasting over half of US kids on the platform, because young people were mostly in lockdowns, or avoiding social contact with others during the pandemic. But to us adults, we thought that these virtual worlds would be the future of where the next generation would prefer to spend their time. Turns out we were wrong.

There was a sense of irrational optimism with the metaverse that the consumer behaviors that changed during the pandemic would be maintained without it. And clearly, this was not true. In a post-pandemic environment, people aren’t thinking about joining the metaverse because they’re too busy living in the real world.

None of this was easy

Outside of the clear branding push that drove metaverse popularity, the confusion surrounding the trend, the humiliating failures in building and attracting users to it, and the economic and social change coming out of the pandemic, there is one more factor that helps explain why we’ve abandoned the metaverse. And that is VR.

The VR headset is supposed to be the hardware that will bring us into a new wave of software adoption. Certainly, that has been Zuckerberg’s big bet. But the challenge with the metaverse was that it was too expensive and too hard to access. For people to try it, they had to purchase a headset for hundreds of dollars, then create an account, and then try the headset on. That’s asking a lot from your average consumer, especially when the value wasn’t clearly demonstrated or accessed.

There was no better way to make phone calls, send emails, or buy products. But there were legless floating avatars, some interesting games, and a few other people on there. The tangible, practical-use cases for the metaverse were not clearly presented to the customer. And because of this, adoption struggled.

Even the practical ideas surrounding workplace collaboration were clumsy at best as CNN reports:

“When a junior manager at the tech-consulting firm Accenture tried to organize her first work meeting in the metaverse, it was difficult to even log in. “I am totally immersed in the metaverse, have a big headset on, and then I need to take off the Oculus, look on my phone for the two-factor authentication code that’s been sent to my phone, then memorize the number, put my headset back on, and try to key it in,” she told me, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “But when you take off the Oculus it automatically goes to sleep mode, and I was trying to navigate the back-and-forth.” She wasn’t the only one who struggled with simply accessing an animated meeting room; by the time the meeting had concluded, some team members still hadn’t made it in.”

When you take into consideration that more than 25% of American adults need help setting up their devices, with tens of millions that have low-tech readiness, it’s no surprise that VR headset shipments declined in 2022 by 12.8%, with less than 10 million products sold globally. When a new tech movement is emerging, then the form factor matters. And VR is still lacking in appeal for the mass consumer.

If you go back to how TMW was covering the metaverse during the 2021 and 2022 peak of hype, I was skeptical of VR in general. The category has a niche purpose with a loyal consumer base, but without the necessary elements that make it a breakout consumer device, it can’t break out into the mainstream. Back then I said this about the technology:

“As most of the attention in VR to date has been in the gaming world, it’s here that experiences are built on top of VR technology and user behaviors are measured and analyzed. The form factor of VR, like the iPhone, and PC before it is driving behavioral change in how people interact with technology.”

But the change was not big enough. The reason? It was inaccessible to people. The technology is not asynchronous and health experts suggest you not spend more than 20 minutes using the devices. The smartphone was a breakthrough technology because you can use it at any minute of the day in most situations. VR, however, required you to be in a quiet place with not many people around to use it.

When you compare ChatGPT – the current breakout consumer technology that recently broke the record for reaching a million users in the fastest timeframe – the contrast is clear. Meta asked you to spend money and make time to use its hardware and software. ChatGPT presented you with a clean, single message box to experience the product on any device, anywhere.

Can the web be more experiential? Yes. Can we find better ways to connect with others? Yes. But I’m sorry. VR isn’t it.

Don’t cry for the metaverse

The metaverse was an optimistic movement, promoted by the best the world has to offer in management consulting, technological innovation, media, and marketing. But its abandonment is a tragic wake-up call for ill-defined ideas during a once-in-a-lifetime historical event.

While some of the ideas of the metaverse are helpful and valuable – namely interoperability between platforms and apps, creating greater immersion in gaming and entertainment, and new patterns for connecting with others – these ideas are all on the fringes of society.

Any one of them needs ruthless execution and focus to gain any real consumer success, but for Meta, the catalyzer of the metaverse movement, their ideas were too broad and unfocused and sometimes confused. In late 2022, Ed Zitron analyzed Meta’s investments and concluded that Mark Zuckerberg was going to kill his company if we went down the metaverse path. It was too much capital deployed way too quickly, for highly speculative ideas without a grounding in problems to solve.

Just like the rest of us, Zuckerberg is moving on from the metaverse, calling 2023 the year of efficiency – a decided shift back into Meta’s core advertising and social products. A course correction that might just save his company from ruin.

And as we all abandon the idea and move on to the next hype cycle, let’s not forget what a truly spectacular waste of talent, capital, and attention the metaverse became during a unique season of internet adoption. Besides, if I had the choice of strapping a VR headset to my head or going to the beach with some friends, I know what I’d choose.

Stay Curious,

Make sense of marketing technology.

Sign up now to get TMW delivered to your inbox every Sunday evening plus an invite to the slack community.

Want to share something interesting or be featured in The Martech Weekly? Drop me a line at juan@themartechweekly.com.