TMW #106 | Nationalizing data

👋 Get TMW every Sunday

TMW is the fastest and easiest way to stay ahead of the Martech industry. Sign up to get the full version delivered every Sunday for this and every TMW, along with an invite to the TMW community. Learn more here.

This week at the annual AWS re:Invent conference, Amazon made a pledge to something called data sovereignty:

“AWS already offers a range of data protection features, accreditations, and contractual commitments that give customers control over where they locate their data, who can access it, and how it is used. We pledge to expand on these capabilities to allow customers around the world to meet their digital sovereignty requirements without compromising on the capabilities, performance, innovation, and scale of the AWS Cloud.”

Another thing happened this week: France banned Google and Microsoft products from schools for storing the data of French citizens in US data centers. This isn’t the first time France has tried to outlaw technologies.

Both AWS and France share a desire for greater national control over data collection, which represents a greater shift towards data sovereignty. According to the ITIF, new laws, regulations and governmental policies that require data to be stored in a specific country have doubled since 2017. The amount and size of fines for breaching GDPR policies are also on an upward trajectory. The question of who owns customer data is becoming increasingly important on a societal level.

These are just blips in a larger picture of how privacy is changing how we collect and use data. It’s what I call the “nationalizing of data”: countries wanting greater control over the data collected on their citizens. AWS has seen the writing on the wall; countries like France, regional political bodies like the EU’s GDPR, India, and state-based regulations like California’s CCPA are all wanting more sovereignty over their citizens’ data. In other words, the days of globalized technology services, powered by distributed data storage are coming to a close.

Data sovereignty is not exactly the kind of privacy regulations marketers are used to. Efforts towards gaining control over citizen data don’t restrict how it is collected, used, or processed. The policies coming into the market are about where it’s stored. If I could put data sovereignty into the context of the shift to privacy, I would suggest that these questions are all about the “where” of data. The “what” and the “why” are addressed in privacy regulation and with technology platforms that deprecate cookies (Chrome and Safari) or mobile app tracking (Apple’s ATT).

If data sovereignty is something that the Martech industry will have to respond to, this begs the question: what does it do to the digital economy when data has to reside in the nation where it was created?

The devil’s detail

Say that I live in Australia, and I retweet something from an American who was quote-tweeting from a person who lives in China. Where should the data live? The easy answer lies in the user's profile and where it originated. The harder answer is very much “it depends”. In this scenario, something about somebody who lives somewhere else is part of my total data collection from my profile.

So, I ask again: where should it live? The answers are complicated. Here’s another example:

Say you’re sharing data between two companies, and you’re using a data clean room or sharing first-party data into an ad network like Amazon or Google. Your company is based in France, but the data center of the ad network (and other affiliate entities) exists in the United States. Where should your data live? Given that there’s a commingling of data from brand to publisher, this creates a gray space that’s hard to navigate.

At this present moment, the rules and regulations surrounding data sovereignty are still in early formation. At best they are superficial, at worse they arbitrarily limit the activities that have been relatively harmless for more than a decade. A globalized world means that data is globalized too.

Nationalizing data appears to be a major step backward in a global economy. If you spend five minutes in AdTech-land, you’ll quickly realize that it’s a dizzying maze of data-sharing practices, tracking, and integrations. There are literally thousands of edge cases that would need to be adjudicated for the regulations to be enforceable.

Despite this mountain of complexity, rules are forming. Dario Maisto, senior analyst at Forrester, suggests that data sovereignty takes on five forms in the European Union:

- Data must be governed by a native corporation;

- It should only be governed by local jurisdictions;

- It must reside in a nation;

- It must be operated by citizens of that nation in compliance with rules and security standards;

- At the extreme edge: global companies cannot operate in companies with data sovereignty rules in place without setting up shop and hiring staff that are citizens of the country they are managing data for.

Now try and scale this list of rules out to 10 different countries, all with varying degrees of severity and nuances in the policy. What you get is an industry that disincentivizes global technology companies from operating, and from startups and brands participating in the global economy.

This might seem like a severe change to data practices that have been around for more than a decade. You might want to ask yourself: what changed? To that, I would say: China and the cloud.

The battle for the data center

Data collection on everyday citizens is becoming a geopolitical bargaining chip in an arms race for technological dominance. In an interconnected world where people share information with others from a variety of countries, this means that the challenges of political spying and outside influence through media channels is many and varied.

But, the challenge must be managed. As the FCC has previously established with the global phenomenon of TikTok, there have been significant attempts to ban the app due to the Chinese ownership of a company where the majority of its data and user base is in the United States.

In this situation, the concern fuelling policy is spying from a hostile state that has increasingly ominous stances toward the national security of Hong Kong and Taiwan – not to mention significant political differences. To the FCC, TikTok’s potential to weaponize the data of ordinary people is far too great.

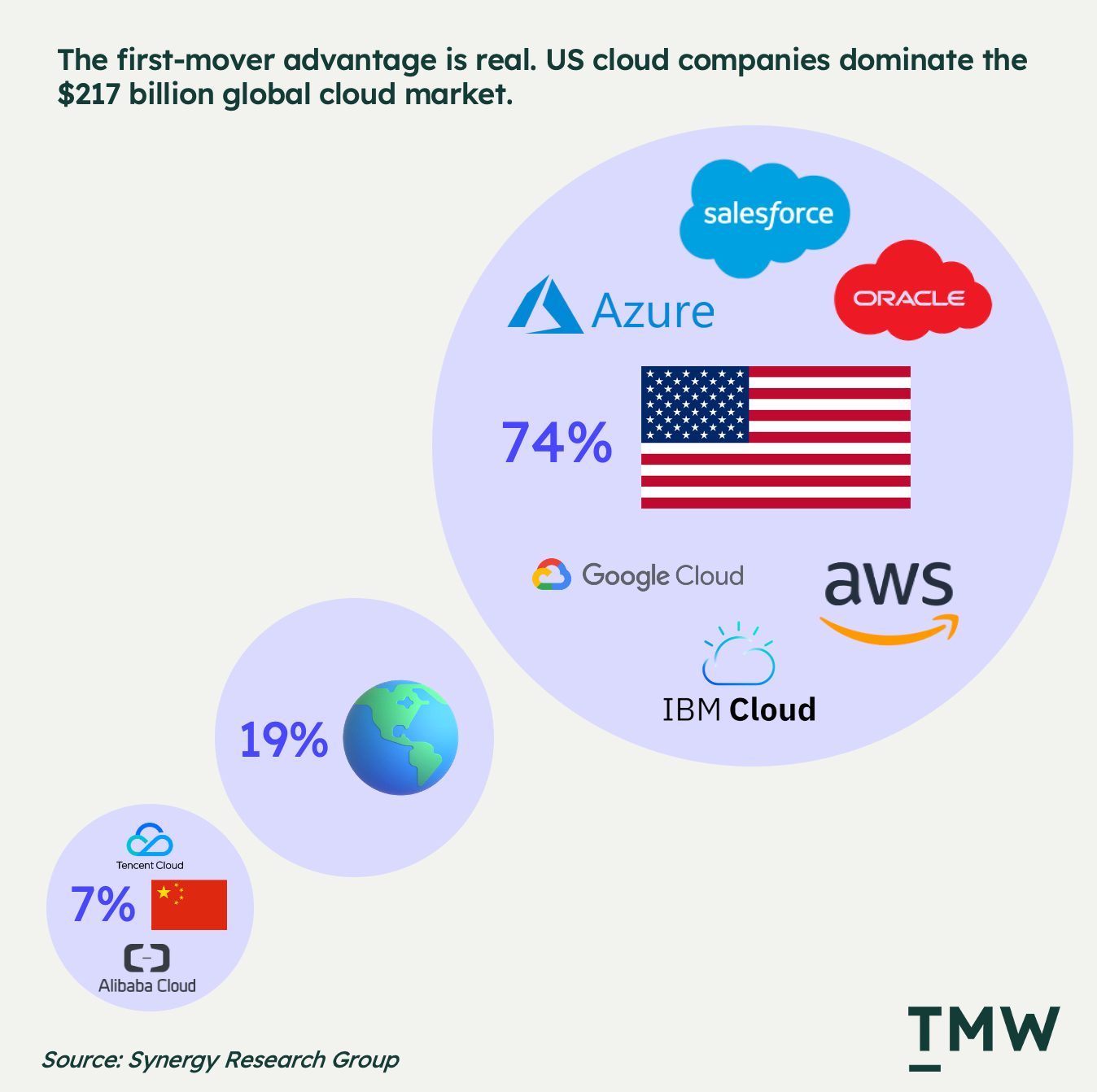

Up until now, most countries have been more than comfortable allowing most of their citizen’s data to reside in the United States. Today, the US runs almost half of all data centers globally.

But now that an outside nation has developed an application that parallels that of US technology giants, coupled with powerful algorithmic enrichment and precise location and preference data on US citizens, all of a sudden, the FCC knows what it feels like to have an outside power have indirect soft power in its country.

The AWS pledge is partially a hedge, stuck in the middle of a turf war for data between nations that are considering how much they should control data collections of their citizens, and how much they should share with other countries. It does open up interesting questions about what makes up a citizen, outside of their physical location inside of their country, place of residence or birthplace. After all, these are all data points. How much does sharing data between nations create risks?

According to the European Union, the risks are great, so much so that the Biden Administration is attempting to establish a data sharing framework called Privacy Shield 2.0. Part of this pact is to ensure that the United States does not use EU data for intelligence activities or misuse. In a strange twist of irony, the United States is concerned about Chinese data ownership in almost exactly the same way the EU government is concerned about the United States.

Data for me, but not for thee

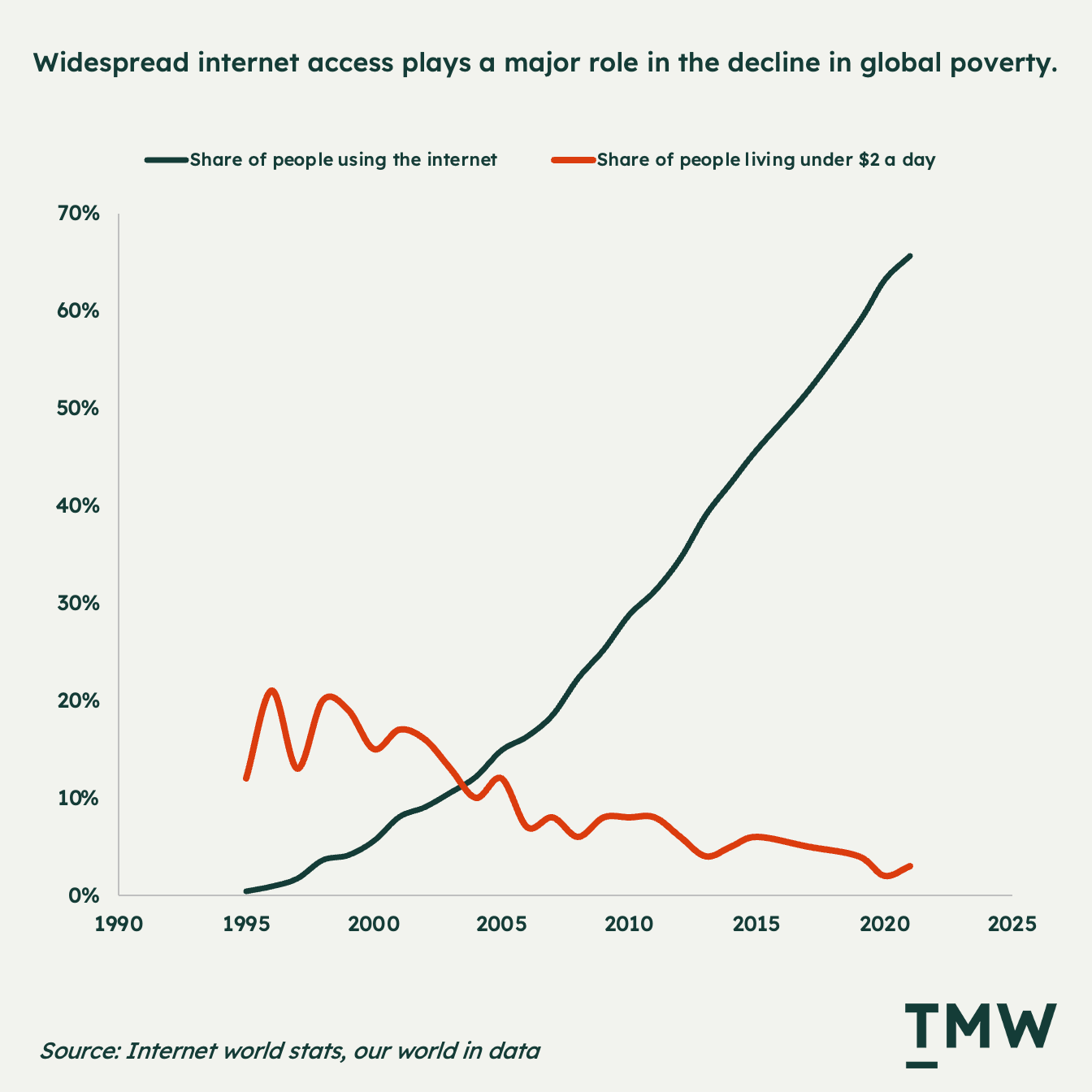

Globalized data has unlocked untold value for countries that don’t have the local technological capabilities to serve their own citizens. The internet has not only provided a platform for entrepreneurs in developing countries to start businesses and connect with customers around the world; it has also allowed for people to build new online communities, create bridges to other nations, and overall uplift the standards of education through the accessibility of information at scale.

All of this has been made possible through corporations that capitalized on the data collection opportunities in emerging nations. In some parts of the world, Meta is literally the internet. Technology platforms have put powerful technology into the hands of the world at very low cost. Perhaps the most costly aspect of this is the exchange of our personal data.

For many nations, that trade has made sense. As the adoption of the web grows globally, poverty also declines. If you can give a 13-year-old kid in a remote town a Chromebook and they learn to code over twelve months, that person has not only learned valuable skills, but also the means to earn income, find career opportunities, and access new business opportunities around the world. The internet, powered by cross-border data sharing and storage, has had the most significant impact on economic opportunity the world has ever seen.

A move towards data sovereignty will force global platforms to provide data centers that are as scalable and robust as they are in places like the United States. Greater costs to employ citizens of data-sovereign countries means rolling back innovation and commodity technologies that millions rely on. For example, Google Docs is free because of advertising that’s powered by data collected from you and stored and aggregated in the United States.

We are just starting to see the rollback of features and services from technology platforms. Recently, Meta has said it will stop offering AR features in Texas and Illinois to avoid the risk of being sued for collecting biometric data on the citizens of those states. Instead of trying to navigate a legislative maze, Meta wants to avoid it altogether.

Ultimately, this creates a situation where wealthier, more sophisticated countries can push back on digital platforms and force them to host data within their countries (data for me), while other countries will have to continue to rely on their digital overlords to collect use and get value out of the data of their citizens (but not for thee). In this way, moving towards data sovereignty will have an inverse effect on global technology access: from unleashing the power of the web for everyone to enjoy, to locking it away behind digital curtains.

Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Oracle and Salesforce represent the major global cloud infrastructure companies. And, love it or hate it, they are responsible for most of the world's access to information, data and opportunity. China is catching up, but right now the majority of the services we enjoy today are running on a US cloud platform.

Another way: Digital nation states?

What is the difference between a social media platform and a country? Balaji has recently been asking this question with a new book on The Network State. If Meta has our personal details, provides digital real estate like a profile and a newsfeed to interact with other people, holds the ability to do commerce, contributes to public discussion, and is governed by its own rules and regulations, how much different is this to a country? Balaji defined it like this:

“A network state is a highly aligned online community with a capacity for collective action that crowdfunds territory around the world and eventually gains diplomatic recognition from pre-existing states.”

Although the concept is crypto-centric, the idea is intriguing when reframed from the context of data sovereignty. We interact with people from numerous countries every day online, and those interactions are often meaningful, commercially valuable and important to global trade. So why try to reel that in with wanting to control the data of a user by their citizenship?

Perhaps data sovereignty is a reaction to the phasing-out of how people participate in society; if citizenship means economic and social participation with a group of other people, then you have a partial city-state in the form of social networks, or a cobbling together of a variety of applications and communication mediums.

Right now, TMW has paying subscribers in numerous countries. It doesn’t matter to them that I live in Australia (or that I have a thick Aussie accent), but it does matter that I conform to the rules and regulations of my payment processor, and my terms and conditions. The influence my country has on my participation in the global economy has very little bearing. Outside of allowing access to platforms, internet infrastructure and a way to establish my identity, there’s not much there that countries control.

While this is an uncertain and entirely esoteric possible future not likely to occur in our lifetimes, the trajectory matters. In a world brought together in hyper-connected, internet-driven forms of citizen participation, a shift towards data sovereignty limits exposure to geopolitical threats but in doing so trades global upward mobility for security.

Martech without borders

Marketing, now more than ever, is a discipline impacted by macro changes like this. The downstream impact changes which apps marketers can use. Imagine for a minute not being able to use Shopify, because it hosts its website platform on an AWS server in the United States. Or, being penalized by the GDPR commission because you unintentionally shared data with an ad network of the citizens of your country. What data sovereignty does is it denies the obvious value created by having their citizens (and their data) traverse borders, and creates a regulatory minefield filled with nonsensical rules.

Nationalizing your data means limiting how much the citizens of a country can interact in an increasingly globalized world. Making it harder for platforms to engage with a country will lead to all kinds of economic disincentives and potentially limit the audiences marketers can reach, especially if they are running global brands selling to multiple countries.

With a globalized workforce that wants to be free to interact with people across borders, data sovereignty seems incredibly short-sighted. What we really need is a UN-led global data protection covenant. Gaining sovereignty over a country’s data means presiding over a worsening economic fate for its citizens. A global problem needs a global approach.

Don’t get me wrong, the risk data sovereignty addresses is real – protecting your country increasingly means protecting who knows what about its citizens. But when analyzed from the perspective of participation in the global economy, data sovereignty may become a bigger problem than the one it purports to solve.

Stay Curious,

💼 The market review preview:

- Stable Diffusion 2.0. Are we close to shutting down the creative department

- Inflation and consumer spending patterns: Customers are holding back

- The ByteDance algorithm. A look into the recommendations engine

- Everything else: Crypto implosion, more Meta fines, FCC and the death of online advertising, spending on the metaverse, Reddit as a marketing channel, and a coffee table book for strategy nerds!

Get the Wednesday Market Review email with a TMW PRO Subscription. It's the easiest way to stay updated on the marketing technology industry. Try it for free for 30 days.

Make sense of marketing technology.

Sign up now to get TMW delivered to your inbox every Sunday evening plus an invite to the slack community.