TMW #134 | Regulating experience

Welcome to The Martech Weekly, where every week I review some of the most interesting ideas, research, and latest news. I look to where the industry is going and what you should be paying attention to.

👋 Get TMW every Sunday

TMW is the fastest and easiest way to stay ahead of the Martech industry. Sign up to get the full version delivered every Sunday for this and every TMW, along with an invite to the TMW community. Learn more here.

Regulating experience

A few years ago, one of my close friends explained something curious about his phone to me. For more than a year, he had switched his iPhone display to grayscale. When I asked why, he explained that it was to combat his compulsion to constantly check notifications and social media.

Perhaps he’s on to something.

The practice of UX – “User Experience” – is changing in interesting ways. Over the past two years, there’s been increased regulatory scrutiny on how companies design products, websites and apps.

This is led by the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTCs) recently revised rules for what they call the “Negative Option Rule” which revamps the rules around how people opt out and are notified about their digital subscriptions. This follows a 2022 report called “Bringing Dark Patterns to Light”, which details all the manipulative, deceptive and harmful UX and UI design patterns and how the FTC is taking action against companies that employ them.

This has culminated in a lawsuit against Amazon stating that Amazon’s Prime subscription flow is intentionally designed to trick users into signing up for Prime and making it hard to cancel. This is how the FTC describes the legal action against Amazon:

“In the latest action to challenge alleged digital dark patterns, the FTC has sued Amazon for enrolling people in its Prime program without the consumer’s consent. Once consumers were signed up, the complaint also charges that Amazon set up online obstacles that made it difficult for them to cancel their Prime subscriptions. According to press reports, Amazon’s in-house nickname for its efforts to deter consumers from unsubscribing from Prime may shed light on the company’s practices.”

The legal action against Amazon for their UX dark patterns and the growing appetite for regulating UX opens up interesting questions about the growing need for rules for web and app design, and what’s at stake for marketers, designers and product managers who all use UX and UI design to grow their companies.

In other words: What does the web look like if UX becomes a fully regulated practice?

The dark side of UX

Dark UX design is a relatively new concept when thinking about design principles and their potential harm. Coined by Harry Bignull, the term defines all the ways in which web and app design can be used to manipulate users to make choices they wouldn’t otherwise make.

European regulators have a very good definition for UX dark patterns:

"Dark patterns and manipulative personalisation practices can lead to financial harm, loss of autonomy and privacy, cognitive burdens, mental harm, as well as pose concerns for collective welfare due to detrimental effects on competition, price transparency and trust in the market”

You can see dark UX design in a lot of different things. In fact, the FTC has been litigating against dark UX patterns for things like a lack of parental controls and adverse design choices for children to buy digital products in games from companies like Apple and Google, enforcing both companies to refund millions to customers. Deceptive Patterns has a hall of shame for companies that employ dark UX practices. It’s a long list. And the FTC is ramping up the regulation and litigation against companies that use it as they are now saying that the amount of dark UX patterns victim complaints is rising.

Coming from a Conversion Rate Optimisation background myself, I can see how this has become an issue worthy of FTC design. Websites and apps are commercial vehicles, and most companies hire people that think about how they can maximize website traffic for conversion, revenue, and other business goals. Analyzing user behavior through AB testing and studying the cognitive biases of people can make for a powerful combination to grow commercial outcomes for brands.

A lot of the choices that go into these kinds of personalization and experimentation programs, without checks and balances, can become a game of optimizing user behaviors as much as possible. A case where this could easily be interpreted as totally fine is Credit Karma and an AB test the company ran which showed pre-approval for credit cards (a proven false claim), and one where consumers were told that they have “excellent” odds of getting a credit card. The pre-approval AB test won, and they set it live.

In fact, there are already dozens of dark UX practices out there according to the FTC’s UX appendix. And you can track which categories they’re in by mapping them to a 2 by 2 quadrant outlining transactions and attention-based dark patterns with tactics that are content or interface focused:

There are plenty of other examples of things that seem fine, but end up becoming a pervasive problem. On the inside of large enterprise companies, it’s not easy to determine what will and won’t become a lawsuit down the road. For example, have you ever wondered why all the new social apps ask for your mobile number? Well, that’s not – in most cases – that phone numbers are critical to you using the app; it’s because people change phone numbers less, making it a more valuable identifier for advertisers. The FTC says that this too is a violation of UX practices.

The problem is mostly due to the newness of dark UX as a phenomenon, and the subjective nature of design itself, one of the biggest problems when trying to put guardrails around UX as a concept.

Regulation is in the eye of the beholder

UX and UI design is one of those things that work subliminally in the internet economy. It’s invisible in that most people don’t pay attention to it and its effects on their content consumption and shopping, but it’s also in everything that’s on the web. Every single interaction online has someone behind it that is thinking about the user’s needs, their experiences, and how to best get the user to do the thing they want them to do. Even the FTC comments that UX patterns are covert and that many users can’t even spot what they are or how they work, and when they are affected they don’t report it because It can be embarrassing to be misled.

This is what makes regulating UX so tricky. Content, design and interfaces are a deeply subjective domain of potential regulation. Deciding what is illegal depends on the cultural point of view of regulators and their actual experience with a product. This is very different from an adjacent (and just as impactful) trend in Martech of data privacy regulation. For one, the interpretation is easier – did you share data without consent? Are you storing info you shouldn’t be? Did you violate the guidelines of, say, GDPR? If so, you’re in breach of regulations.

Ben Thompson argues for this point that the legal action against Amazon’s so-called dark patterns can be chalked up to nothing more than a company just trying to promote a high-quality product to its customers. What’s wrong with that? From Stratechery:

“Set aside all of the discussion above about the overall value of Prime and the problem of free-loaders: this specific part of the complaint is absolutely ridiculous. Amazon’s flow — at least as depicted by the FTC in their own complaint — is completely reasonable, and that’s even before you start discussing the contrast with entities that let you sign up on the web but only cancel by call. Amazon’s entry into the cancellation process is clear, the flow is clear, and it’s not a crime that they seek to educate would-be cancellers as to why they might not want to cancel.”

Ben goes on to point out the obvious contradiction of the FTC lawsuit claim: That Amazon is designing to limit information when users sign up but assumes that users don’t have prior information when users cancel. And I agree with him:

To put it another way, the FTC’s complaint about dark patterns when it comes to signing up for Prime is rooted in the assumption that consumers lack knowledge and are easily tricked; the FTC’s complaint about Amazon presenting reasons to not cancel is rooted in the assumption that consumers are already fully-informed and ought to be able to accomplish their goal in as few clicks as possible. The better explanation is that the FTC is simply anti-business.

On the face of it, it’s ridiculous to use two different standards in a single allegation of a company using dark patterns to trick users. And that kind of proves my point here: UX regulation is a slippery slope. But I disagree that this is just Amazon designing for growth and retention. Optimizing design to make tasks harder or easier for consumers based on your commercial goals can easily veer into unethical behavior. And if you’ve ever tried to cancel a New York Times subscription, you’ll see why the FTC needs to litigate against dark patterns.

This is what makes the legal action against Amazon so interesting as a watershed event for how the web should be designed into the future. But there’s more here. While the FTC focused on retail cases of UX dark patterns, there are other categories that are more damaging to society and consumers that is underdeveloped and totally lacking critical thought from the agency.

Cocaine, cigarettes and porn

New York had a massive cocaine problem in the 90s. Fuelled by Mexican Drug empires, party and rave culture, and a substance that is highly addictive and destructive flooding the streets, it was so bad that the government had to create new rules and laws to counter it with zero-tolerance street policing tactics. But by doing so, the NYPD reduced arrests by almost 100,000 a year.

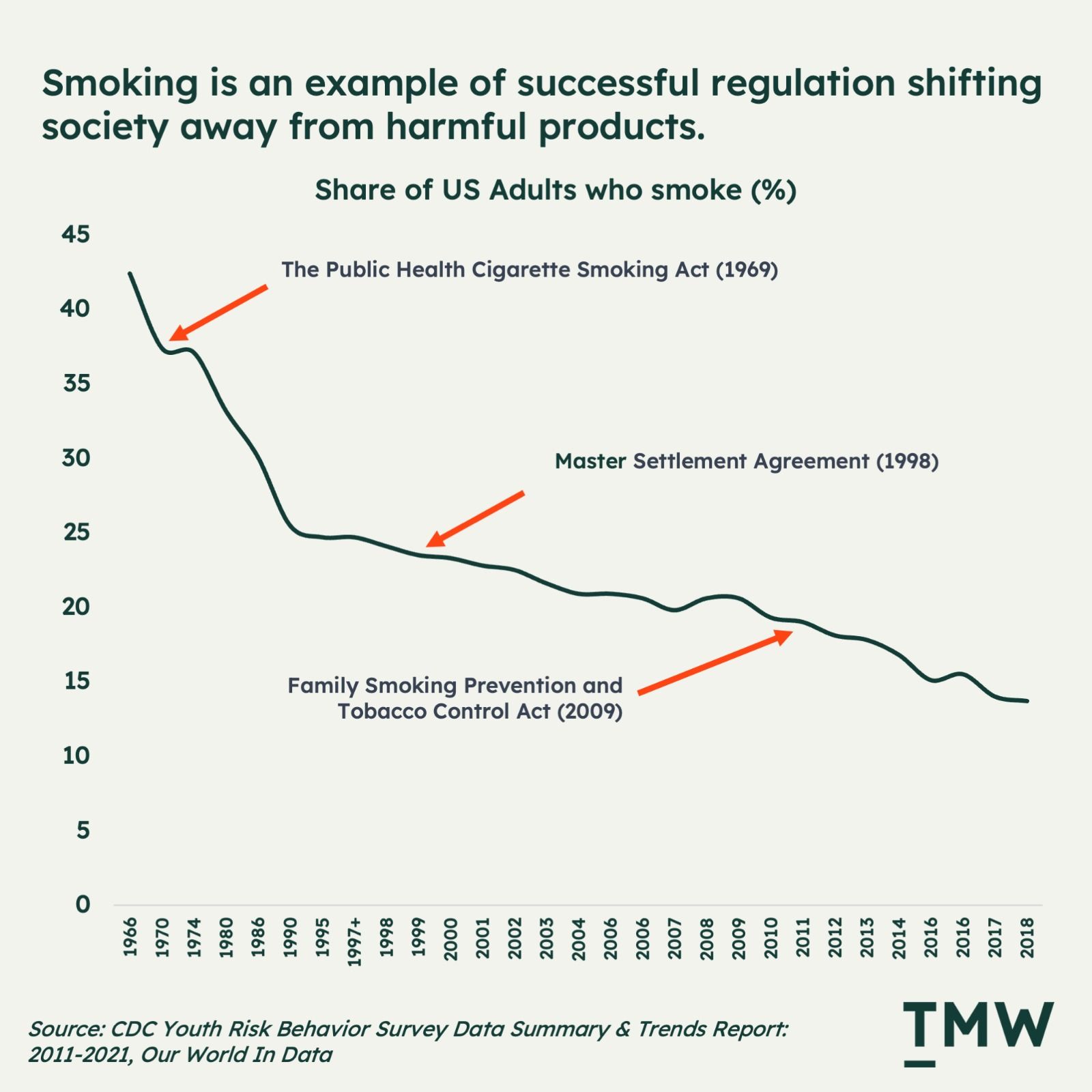

Smoking is another example of massive change through regulation. It’s not as destructive as cocaine, but it’s bad for you and it’s addictive, just on a different time scale. For example, my mother chain-smoked herself to death but lived a relatively long life. Talk to someone who’s quit and they’ll tell you that it’s one of the hardest things they’ve done in their life. But the US government’s regulatory actions have transformed something that was mainstream into a tiny outlier of society.

The internet has its own sources of addiction. Pornography is one of the big ones, with some of the larger sites garnering more than 3 billion website visits a year, along with the exponential growth of neo-porn subscription websites like OnlyFans that are just as addictive and destructive.

Mainstream porn sites also use deceptive UX dark patterns to trick users into doing things; it’s part of what makes these sites so addictive. In fact, sites like Pornhub could run a master class in deceptive design tactics. Porn is one of the many evils that exist on a free and open internet.

Alcohol, cocaine, methamphetamines, gambling, smoking – these are all examples of things that became vices for society and were dealt with by regulation and legal action in previous generations. But I think we’re starting to see a similar shift in perception of things like social media – another type of addictive substance.

The optimistic case for regulating UX is that it might be able to do for the web what regulation has done to all of the substances I’ve mentioned. Governments should be thinking about protecting people from an addictive substance in the form of scrolling algorithmically optimized content streams mindlessly and creating content for attention.

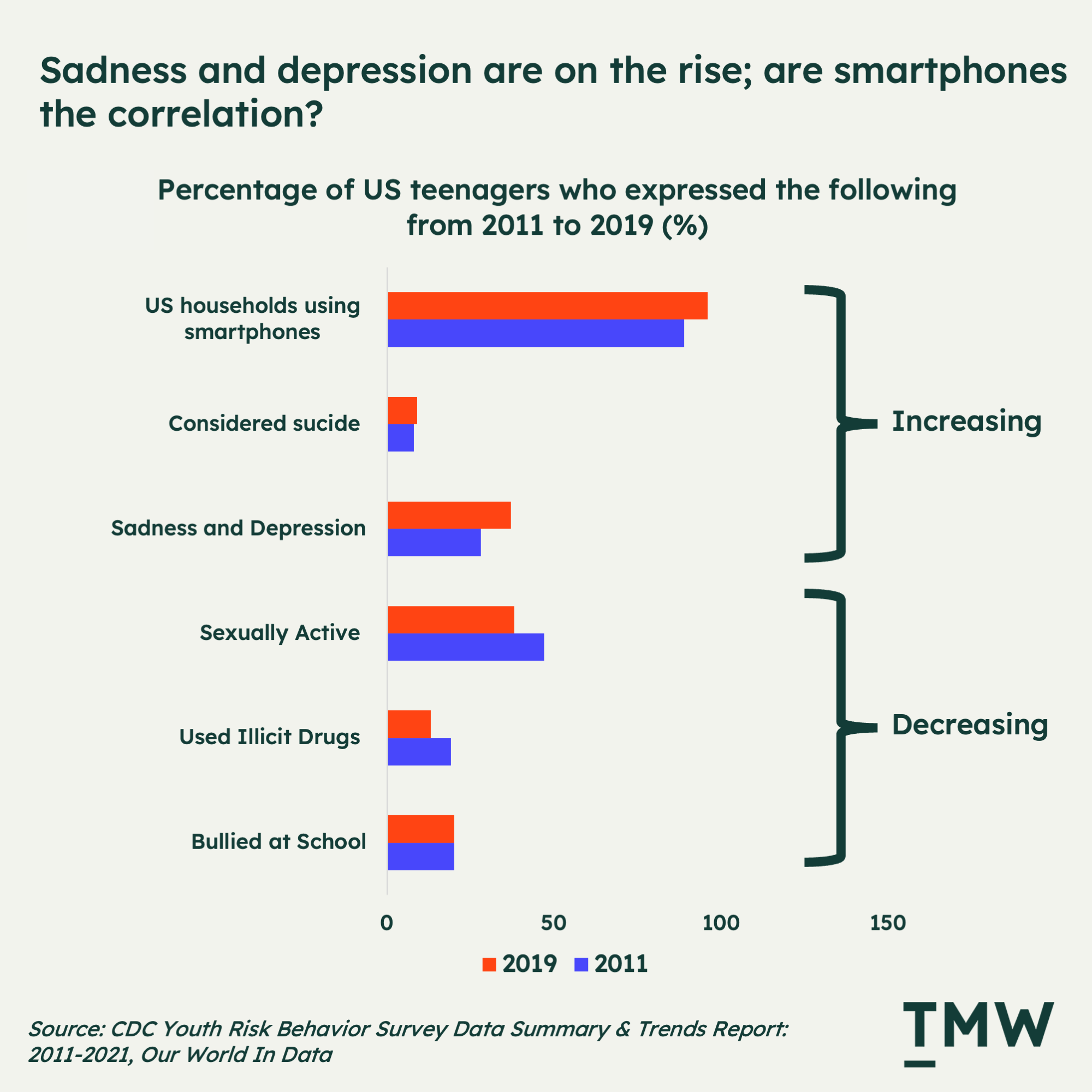

It’s already starting to impact society: the 24/7 ability to socialize with other people is doing more harm than ever. We are more depressed, having less sex, more lonely, less present with our loved ones, and overall just sadder as a society.

If you look at how the life of the teenager has changed in the digital age, the difference of just ten years has marked a significant shift in what young people are doing. According to the CDC, US teenagers are having less sex, use less illicit drugs, and are bullied at school less frequently. But, they are more suicidal and experience more depression and sadness. What’s the correlation? More smartphones, and social media use. To paraphrase Noah Pinion on what’s causing this: It’s probably the phones.

But the challenge here is that unlike smoking, hard drugs or pornography, the substance itself is us – we are the drugs. When you interact with someone online, it releases those feel-good chemicals in your brain like dopamine and oxytocin. And the more you do it, the more you crave it.

The desire for status and attention is deeply seated in our psychology. And the fascinating thing here is that social media companies like Meta, Twitter, and most recently, TikTok, have been able to convert these needs and vulnerabilities into highly profitable business models. Facebook famously learned years ago that when people tag each other in photos and it sends users an email notification – it’s impossible to resist.

Even Meta’s new Threads app has a lot of UX dark patterns designed to lock people in and keep them engaged on the platform. Zuckerberg’s brilliance has never been his technical prowess; it’s been his understanding of how technology intersects with human psychology.

But even worse is TikTok’s supremacy in designing products to get people to consume and create more and content. It’s how you end up with engagement-maximizing videos like this:

One Twitter user commented on this live stream with the best way to encapsulate what is happening here, saying that “this woman is a hyper-optimized window into the collective unconscious. It’s obvious that she has spent hundreds, perhaps thousands, of hours studying the exact sequences of gestures and phrases that maximize viewership and revenue.” Indeed it’s not only the companies constantly optimising for our attention, we do it to each other and ourselves.

This video is just one of millions of examples of psychological tricks people will use to make money and build an audience. The endless streams of rage, lust, envy or engagement bait content for clicks and engagement is not the direct fault of social media apps. It’s humans optimizing themselves towards goals they perceive to be important. The design of the app, and more importantly, its algorithms, shapes what gets rewarded. People are just finding ways to hack people’s attention within the boundaries of social media app design.

I call this The Contentification of Everything, where optimizing for engagement goals – no matter the cost – is becoming a defining problem of the wasteland social media has become. We’ve become way too good at hacking each other’s emotions for attention, clicks and sales. And now, the next generation wants to become content creators more than any other mainstream career choice.

For these reasons, this is why I find the FTC’s actions against Amazon so mind-boggling. Sure, Amazon Prime’s UX can be perceived as deceptive. The argument makes sense that designs choices to a direct fiscal loss for consumers as they are being tricked into purchasing something they don’t need.

But the bigger elephant in the room is the UX patterns surrounding social media platforms on the web. Deceptive practices to dupe people into buying things is something that has a long tail of regulatory history. This makes Amazon an easy target for the FTC. But the real impact of regulating UX will be figuring out a way to put guardrails around what is now a free-wheeling, open space of experimentation: social media design and algorithms.

Sara Morrison from Vox describes TikTok’s design choices as a dark UX problem. The design reinforces the algorithm that’s changing the behavior of content discovery from searching and finding to passive consumption:

“If you want to see another video, you swipe up and something new appears. You don’t get to choose from a list of related content, nor is there any real order to whatever you’ll get. The videos can be fairly new or months old. But you won’t know either way, because there aren’t any dates on them. If you prefer to be a more active participant in what you watch, you probably won’t get it. But the appeal of TikTok for so many people — and what makes it so addicting — is that unending stream of “for you” content.”

This is the missed opportunity that the FTC doesn’t seem to be investing a whole lot. Perhaps because lost or regretted time isn’t seen as impactful to consumers as a financial loss. But if there’s anything that needs regulating, it’s the algorithm.

Before / After Algorithm

The defining historical view of the internet is traditionally known as Web1 and Web2, which usually goes along the lines of Web1 was about reading, but it was hard to write on the web. Web2 was about allowing anyone to read and write stuff on the web with the dawn of social media, search, the cloud and other tools.

But I think the bigger, more impactful shift is when websites became algorithmically optimized. Powerful algorithms have given us huge social media platforms that suck up the world’s attention and time, creating huge moats of network effects. It’s one of the world’s more impressive business models ever conceived.

And it’s working. According to eMarketer, 3.8 billion people will be using social media networks every month in 2023, which is close to 50% of the world’s population.

But since then, the algorithmic optimization has become a huge user experience problem. As they become more powerful, they become huge black holes sucking everything toward themselves. All of our creative output, our attention, our shopping, advertiser dollars. Back to Morrison’s explanation of how this is working out in practice:

“…But platforms wouldn’t be doing this if the strategy weren’t so successful. This is the experience users want, or at least they’ve become convinced it’s what they want. It’s been decades since internet access was introduced to the mass market, and the novelty of endless choice has worn off. There’s something to be said for having something or someone else pick what you see and do. Which is how things used to work before the internet, of course, just not with the granularity that’s possible now.”

The problem is that powerful algorithms are not just shaping how we experience apps, but how we experience the internet itself. Algorithms are enabled by design and power similar goals and they should hang together.

The UX police

Given the exponential potential for harm that deceptive, manipulative dark UX patterns represent. The real question here is if they should be regulated or not. Right now, freedom of expression is a human right, but not a corporate right, and UX sits somewhere in the middle of that.

Who gets to decide what is a dark pattern or not? We’ve never really put regulatory guidelines around UX principles in tech before, so what does this do to the internet? Will there be regulatory frameworks and checks that local governments carry out for companies that we see in accounting, legal, and other highly regulated industries?

This is a hard needle to thread. Putting arbitrary rules around how products and apps can be designed can kill innovation, but letting it run unfettered will make us all dumber, more cheated, and more depressed and isolated.

Regardless, the same arguments can be made about the airline industry, smoking, methamphetamines, and other potentially harmful substances. Limiting them stifles innovation. But as we’ve seen just over the past couple of weeks, building products by side skirting regulations can lead to destructive outcomes.

I think the future of the internet has to become more regulated because, like it or not, the market will eventually decide what should exist and what shouldn’t. And there are a lot of concerned parents out there watching their children waste their life scrolling social media and spending time playing video games, which should change the perception of how these apps are designed.

We’re already regulating how some companies like banks and insurance companies can talk about their products and services. TV commercials have regulated frameworks in place. There’s a lot of justification here for regulating UX design, no matter the gray space surrounding how the rules will be created and upheld.

This will make personalization and experimentation programs harder to run. But the cost of this might lead to a healthier internet where not every single app is ruthlessly optimized to waste our time or money.

What this all comes down to is: what kind of internet do we want to work and live in? Laws and rules create order. Criminals must be sent to prison for the rules to work. I remember walking down into the Mission District in San Francisco recently and feeling incredibly unsafe. Why? Lawlessness is everywhere, open-air drug dealing happening on every block, pervasive homelessness and mental health problems, and drug use is eating away at the city because the police are not empowered to enforce the law. Metaphorically, the web will end up just like downtown San Francisco if dark UX patterns persist. Regulation is inevitable.

Stay Curious,

Make sense of marketing technology.

Sign up now to get TMW delivered to your inbox every Sunday evening plus an invite to the slack community.

Want to share something interesting or be featured in The Martech Weekly? Drop me a line at juan@themartechweekly.com.