TMW #109 | The chaos of cookie fallout

Welcome to The Martech Weekly, where every week I review some of the most interesting ideas, research, and latest news. I look to where the industry is going and what you should be paying attention to.

👋 Get TMW every Sunday

TMW is the fastest and easiest way to stay ahead of the Martech industry. Sign up to get the full version delivered every Sunday for this and every TMW, along with an invite to the TMW community. Learn more here.

The chaos of cookie fallout

The thing that fascinates me about third-party cookies is how dualistic it is to society. On the one hand, it unlocked untold trillions in value in the global economy and was the core tech that made many of the services on the web free for everyone – and in doing so, alleviated poverty for millions around the world. On the other, third-party cookies invade the privacy of everyone they touch, enable internet monopolies, play a large role in disinformation, and of course: cookie popups.

But the ‘both-sides’ issue of third-party cookies is becoming a thing of the past. It’s 2023, and marketers and advertisers are slowly (and painfully) moving away from the technology that’s powered online marketing for more than 20 years. The problem is that we have no idea what we’re moving towards. The state of post-third-party cookie marketing is chaotic – a minefield of risks and opportunities.

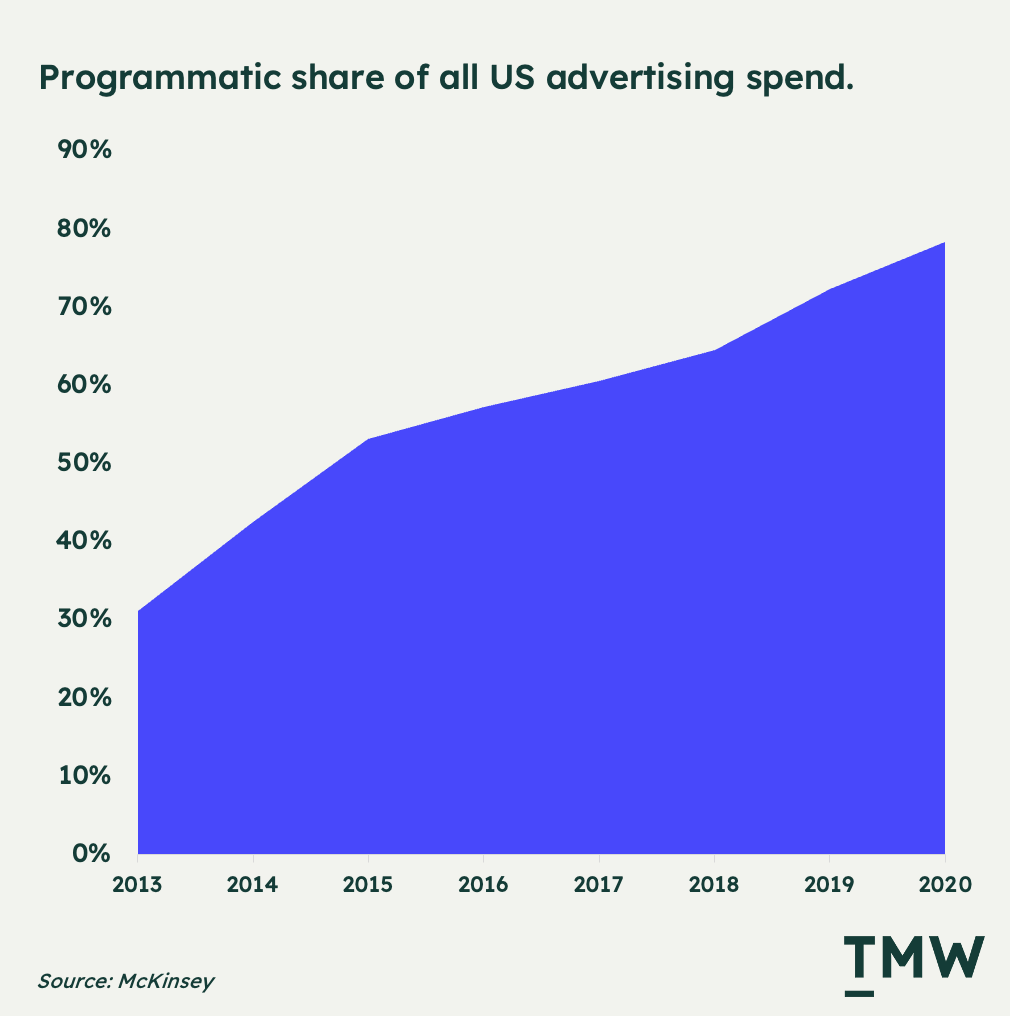

Why? Third-party cookies is the lifeblood of the free and open web and the technology underneath an estimated $10 billion in publisher revenue, with programmatic controlling almost 80% share of the advertising market. It has a staying power like no other marketing or advertising technology. Walk outside and imagine ripping up the roads and the streets and rearranging them into a new configuration. Figuring out what should happen after cookies is like that.

Now almost three years after Google announced a plan to deprecate cookies and more than six years after Apple made its first moves towards blocking cookies, we’re no closer to a winning solution for how marketers should be tracking and targeting users on the web. And it’s wreaking havoc in the industry, spawning start-ups and a dizzying array of new products from the AdTech incumbents while boosting the popularity of new channels. There’s a lot going on.

The remembering machine

Third-party cookies feel like a dirty technology. It’s mired in spammy, weird advertising, banner and sidebar ads, and the yuck feeling you get when you’re shopping for shoes and then ads pop up everywhere on all the other sites you visit. There’s a reason for that.

The story of the third-party cookie is kind of like a Greek tragedy, filled with innuendo, controversy, and a vain pursuit of too much, too fast, all to have it end with its eventual demise.

The name “cookie” itself is ironically inspired by fortune cookies, representing a dessert with a message embedded inside. The invention came about from an e-commerce project where a Netscape customer did not want to have to store every single user session and retrieve it when a user returned or navigated to a new page. Back then, the web didn’t have a way to remember, even from page to page on the same website.

And so the cookie was invented in the lab by a 23-year-old engineer, and made publicly available on October 13, 1994, on the Netscape Mosaic browser via a software update. It wasn’t until two years later in February 1995 that the public was made aware of this novel technology with an article by the Financial Times about the “smart bug” in your computer.

Almost immediately after third-party cookies were released, they were mired in privacy controversy. Like a bad smell, cookies have always been associated with privacy concerns. It took years for security and privacy compliance to be developed. The first attempt at creating standards for cookies was developed by their inventors, but the first browsers to use cookies – Mosaic and Internet Explorer – did not even adhere to the standards they themselves set out. The FCC even discussed the technology as a privacy threat not long after its invention.

Back then there were two problems on the internet: how do we make information easier to find, and how do we monetize it? Third-party cookies became the cornerstone solution to the monetization problem of the internet.

By storing a cookie on someone’s browser, the internet had a significant advantage over all other advertising formats: the media can learn about you and show you something more relevant than any television, print magazine or billboard could ever hope to do. It also made it easier to shop online, stay logged into sites and remember your preferences.

Back then the technology was not sophisticated, with some analysts suggesting that based on today’s GDPR policies, the cookie of 1994 would have been compliant. From those early days to today, advertising technologies have evolved the humble cookie into a complex web of trackers, data-sharing networks and audience-matching solutions. 1994 feels like a long, long time ago.

Because the third-party cookie was an invention of the browser, and the browser is the window into the web, it meant that there was very little commercial control over the technology. Along with open protocols like HTTP and SMTP, the cookie helped to pave the streets of the internet we know today.

28 years later, marketers and advertisers have grown into an overreliance on this ancient technology to do marketing and advertising. And while more gated forms of data collection have grown up around the cookie like social media sites and e-commerce behemoths with new beacons and trackers, the open-source nature of third-party cookies, coupled with pushing the management and storage onto the user, makes cookies one of the most successfully enduring technologies in the internet age. In other words, cookies are like cockroaches – almost impossible to kill.

The outlook the Financial Times gave to cookies back in 1996 is prescient. This valuable technology ushered in the age of programmatic advertising, one of the most powerful forms of performance marketing ever invented:

"Yet the tale of these cookies is an illustration of the possibilities that internet marketing opens up. In the old days, placing an advertisement was like firing a blunderbuss; remember the old quip that half the money spent on advertising was wasted, but no-one knew which half. Today, technology has created a silver bullet that allows companies to target people individually."

The death of a stalker

Cookies have always been a contentious technology, but after all this time, they are going away. But why now? What’s so special about the 2020s that makes cookies an evil that must be ripped out of society? The third-party element of cookies– and some of the AdTech solutions that leverage cookies – is being regulated into the ground, cut off by browsers and abandoned (reluctantly) by the AdTech empire built around it.

Firefox was one of the first browsers to disable third-party tracking way back in 2013, followed by Apple in 2017. Against the criticism of the AdTech industry, and potentially threatening the viability of millions of internet companies that rely on cookies for ad monetization, Apple made the unilateral move to introduce intelligent tracking prevention. The GDPR then came into force in 2018, giving us the godawful cookie banners you love to ignore on any website that touches Europe.

And it’s only been a few years since Google decided to follow their browser peers by announcing cookie deprecation and then delaying three times with an estimate set for 2024. As soon as Google made that initial announcement in 2020, the AdTech industry scrambled.

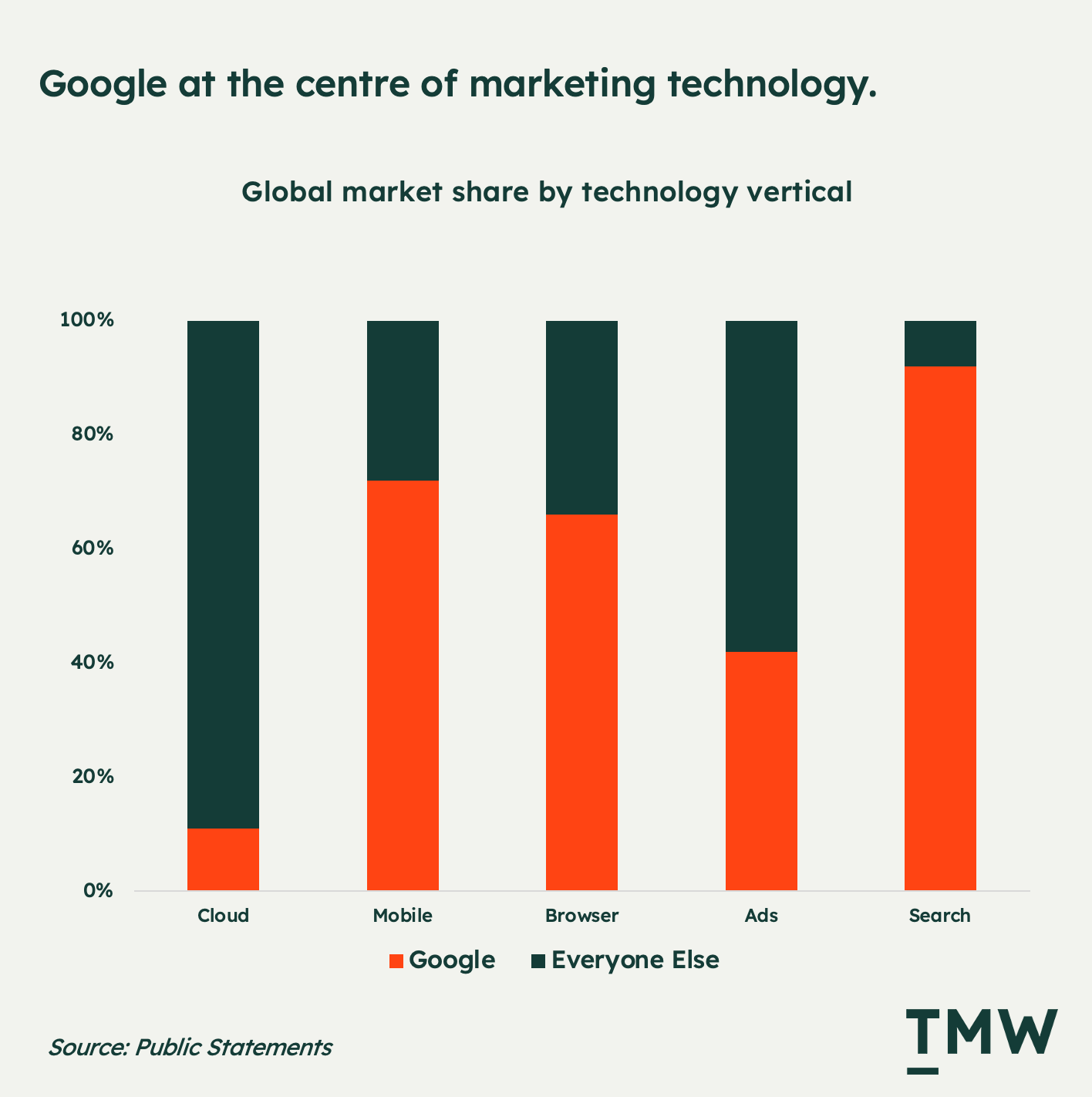

Safari was an issue and Firefox was always an outlier, but Google’s Chrome browser sits right at the epicenter of the AdTech empire that relies on third-party tracking. When it comes to the internet advertising ecosystem, all roads lead to chRome. (See what I did there.)

Who killed the cookie?

It’s interesting to note that most of the cookie deprecation conversation is dominated by the imperative for a more private web. It’s not that the technology is so old that it's teetering on obsolete, or that the shift to mobile and new web formats is introducing new frameworks for identity management are good enough reasons.

The entire shift to a cookie-less web is predicated on the current, imagined, and potential harms toward human privacy. But we put up with it for more than 20 years. What gives? GDPR and CCPA policies have been instrumental in uncovering how third-party trackers work and creating legislation to approach ways to minimize harm.

But I think internet literacy and generational change have given us a population that is far more concerned about their online privacy, mostly because people know more about what makes free websites like Instagram and Google free. That’s one angle.

The other angle is that AdTech has been woefully inefficient and opaque for advertisers. According to Augustine Fou, the murkiness of AdTech has become a flashpoint in wasted ad spend and is in need of reform.

The problem is that cookie-enabled tracking and targeting have become the mafia and the complex web of relationships, criminal behavior, and shady money passing hands have become impossible to penetrate. If you work for the Trade Desk, you might as well say you work for Tony Soprano – you’ve kissed the ring and are in the gang for life.

And then you have Apple’s land grab for advertising dollars. Apple’s move into the ad business is important because it shows us that a future without third-party trackers is not one that will enable new companies to enter and offer new marketing and advertising technologies, but it will likely become just another changing of the hands into other larger AdTech players. That’s exactly what Amazon’s attempting to do by bringing the buy with Prime button to e-commerce retailers – it’s a land grab for customer data on the open web.

Cookies are slowly dying in the same way they were born: mired in controversy and confusion.

Life after fallout

Because of these changes to the industry, the central question in 2023 is this: what are we going to do now? Well, as cookies depart stage right, a rabble cast of unfamiliar characters takes center stage. Once this so-called evil technology is wiped off the face of the planet by the browsers that command our devices, what happens next?

There are somewhere in the ballpark of more than 100 companies working on cookie replacement technologies. But outside of direct replacements pioneered by the AdTech companies with the most to lose, all kinds of other approaches are forming.

Emerging out of chaos are three streams of thinking about what should happen next, which follow the logic of replacing cookies, rewriting what advertising data should be, and rethinking the whole premise of highly targeted programmatic advertising.

The first is a replacement technology, cookie technologies like ID5 and UID2.0 are leading the way for a new kind of publisher, brand, and customer relationship – one that leverages the first-party cookie to send audiences to various publishers. The attempts to create a new cookie format might be a space for ground-breaking innovation, or just flogging another horse, one that will be dead on arrival.

Another stream in the rewrite camp is the shift to first-party data. This takes the form of some kind of CDP data enrichment and conversion API maneuvering to get data from core systems and your website and matched with custom audiences or publisher lists for better targeting.

In this stream we have a lot of interesting shifts, from the rise of walled garden ad networks like Apple and AWS, to the growing popularity of data cleanrooms for shared anonymized data between platforms. Retail media is another aspect that is driving marketers to work directly with first-party data-rich environments like large marketplaces and e-commerce retailers. We’re quickly getting to a point where the word ‘marketplace’ is basically interchangeable with ‘ad network’.

As the third-party well dries up, everyone is scrambling for water, and the closest well is first-party data. But the problem here is that first-party data was primarily designed for owned channels and for safety and authentication purposes. Trying to contort this data format into something that will please advertisers is a recipe for either major privacy breaches, data contamination, and/or poor results.

In all honesty, it’s probably going to be all three. First-party data is less plentiful, harder to access and it’s more challenging to get privacy right. It’s like if your leg got cut off, you respond by putting a Band-Aid over it. That’s why probabilistic cookie replacement technologies are becoming more popular.

Contextual is the last and one that departs entirely from the premise of data sharing with publishers. The internet opened up the possibility of targeting users down to the most inane granularity, but contextual advertisers and the technology ecosystem that enables it is taking a different path. By using the data that exists within the publisher’s context advertisers are able to target broad-based behavioral and content interests. As Benedict Evans once made the observation:

“Advertisers do not, by and large, want to know every intimate detail of your life. P&G wants to show diaper ads to people who have babies, not show them to people who don’t, and have some idea of which ads worked. They don’t care about *you* at all.”

What I like about contextual advertising is that it calls into question the whole premise of precise targeting. There are more sites than ever with rich, deep, and broad content, so why can’t we use the powerful data to meet marketing goals without having to share it?

We used to care about the Internet

Although the three streams of thinking about what’s going to happen next solve various problems, all three approaches are incoherent to the needs of the broader internet, and society at large. Driven by self-interest instead of a genuine interest to make the internet a better place for consumers, I have little confidence that anything without a direct commercial outcome will win the next wave of advertising technologies.

You have to give credit where its due, there are very few technologies that did a better job of balancing societal and commercial benefits than third-party cookies.

Readers often ask me why I go on and on about cookies. After all, isn’t this all about the advertising side of technology? My answer is always this: cookies are systemic to the kind of internet that makes marketing technology powerful or ineffective, and figuring out what will happen next is imperative not just for how the marketing department will reach and convert customers, but also for how everyone will use the internet. There is no other critical matter to address in 2023 than how the internet pays for itself.

Should AdTech companies really be the ones to solve this problem? They’re the ones that created it in the first place, but from Lotame to The Trade Desk, every single AdTech vendor has alternative identity solutions, saturating the market and creating excessive complexity when it comes to choosing and using these new tools.

After all, the original cookie was invented by a browser company, and while Google hasn’t yet figured out what needs to happen, and has failed to make things like FLoC work, they are likely the company to create a new standard, whether we like it or not.

Cookies gave the internet so much, but also present an enduring and existential risk to society. But perhaps instead of asking what we do after third-party cookies, maybe we should be asking: what kind of a Martech and AdTech industry do we want to create?

Figuring out what happens after the fallout of cookies is imperative if we want the internet to persist as a place where everyone can grow a company and access free information and service without sacrificing the privacy of regular people.

Stay Curious,

Make sense of marketing technology.

Sign up now to get TMW delivered to your inbox every Sunday evening plus an invite to the slack community.

Want to share something interesting or be featured in The Martech Weekly? Drop me a line at juan@themartechweekly.com.