TMW #117 | A hypothesis for hype

Welcome to The Martech Weekly, where every week I review some of the most interesting ideas, research, and latest news. I look to where the industry is going and what you should be paying attention to.

👋 Get TMW every Sunday

TMW is the fastest and easiest way to stay ahead of the Martech industry. Sign up to get the full version delivered every Sunday for this and every TMW, along with an invite to the TMW community. Learn more here.

Some news: This weekI’ll be joining Scott Brinker and Tejas Manohar to discuss the emerging role of warehouse-native marketing technologies in the future of the Martech industry. Register for free here.

"I believe that the abominable deterioration of ethical standards stems primarily from the mechanization and depersonalization of our lives… A disastrous byproduct of science and technology."

- Albert Einstein

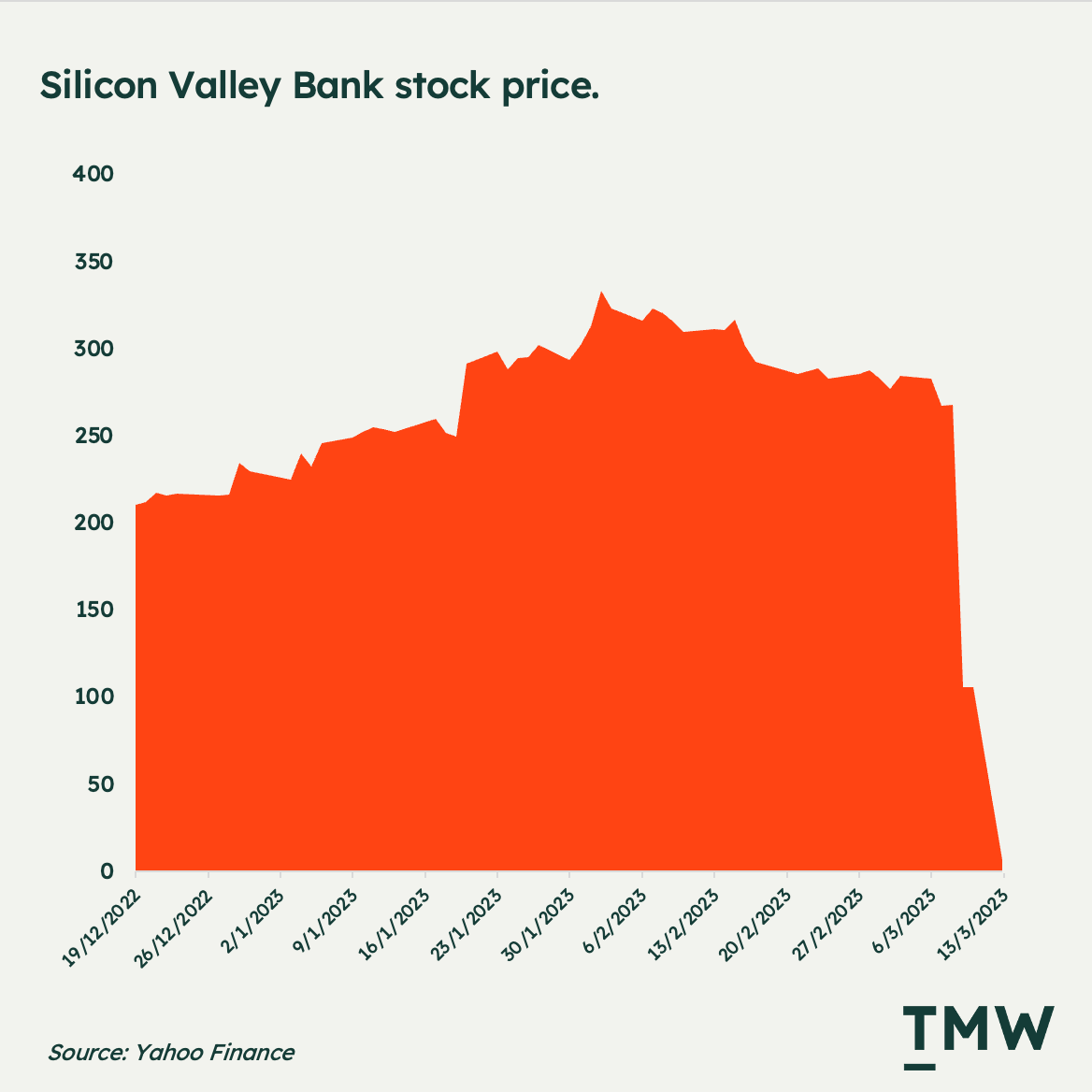

This week Silicon Valley Bank almost met a total collapse. SVB is the United States' 16th largest bank with more than $175 billion in deposits, servicing a large chunk of the startup ecosystem – including a wide variety of marketing and advertising technologies. Over the past few weeks, the company attempted to make strategic changes to its investments, cut short its losses and counteract rising interest rates – things most other banks were doing given the unstable economic situation and general downturn.

And while SVB was a company in financial trouble, it was not totally insolvent. But instead of calming investor fears, SVB triggered a bank run that caused $42 billion in transfers in a day, triggering a company shutdown and a moral panic lasting a weekend. It also caused several other banks to go into FDIC receivership.

What could have caused such a spectacular bank run overnight? The answer is messenger apps and social media.

SVB doesn’t have much to do with Martech. But the way its collapse came about has a lot to do with how technology intersects with human attention, media and marketing, creating, to quote Einstein, a “disastrous byproduct” called hype.

I have a hypothesis for how hype has changed how we learn about new technologies. Hype used to be a natural way to promote useful new technology, but it is increasingly becoming an end in and of itself. Instead of hype working as a cycle, it’s becoming more like a spiral – a machine constantly churning out new things for us to care about only to discard them at a moment's notice.

No one cares until everyone cares

There’s something curiously similar to SVB’s collapse with that of the 2021 GameStop price manipulation situation, the wild speculation on Web3 projects, the ongoing layoffs, Elon Musk taking over Twitter, FTX’s spectacular collapse, and the destruction of crypto project Terra Luna. All of these situations were mediated by an algorithmic herd mentality, primarily through Twitter but also through a variety of other social media platforms. And it seems as though these cycles of herd mentality are only getting faster.

We’re heading into uncharted territory with access to information. Despite there being literally unlimited things we can learn about online, with ungated access to knowledge and education, and opportunities to meet new people, we seem to prefer following the algorithms designed to keep us fixed in one place. In a way, we’ve given over our own concept of agency, because scrolling Twitter or TikTok is a more convenient way to gain the information that we want.

What this is creating in society is an ever-increasing homogenization of what people pay attention to. SVB is one example of the main character dynamic on social media. As Andy Warhol once famously said, “in the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes” this prediction has mostly come true: a breakout new technology, a viral post, or a controversial situation happens, and algorithmic content machines make us care about whatever is happening at that moment, thrusting ordinary people into the limelight in front of an audience of millions of people.

When I was in high school, there was the occasional school fight. You know the ones where a bully will pick on a kid and eventually that kid retaliates? When these kinds of things broke out, all the kids would rush to watch it. Eventually I would overhear some of the kids ask, “Hey, why am I running?” to which the answer would be: “Because everyone is.”

I can’t think of a better metaphor for our attention economy than this. Most of us care about certain issues, topics, technologies, and marketing tactics because, well… everyone else seems to care about them. The human mind’s vulnerability to herd mentality is powerful, and no one benefits more from it than marketers.

Who benefits from hype?

A great example of this is the hard pivot many marketers, technologists, and indie hackers made from Web3 to the generative AI trend. I have whiplash from when everyone went from saying that there’s a new decentralized web and it’s going to be a glorious new future powered by the blockchain, to generative AI being the transformative shift that will change everything about the internet.

Venture capitalists, journalists, podcasters, and newsletter writers (guilty as charged) all made that pivot. Public opinion can create a bull market or a bear market and while it can launch startups out of nothing it can also send them to the grave. This invisible power continues unabated as a major cultural force that’s reinforced by selective content algorithms and exponentially networked people.

That’s why we have what seems to be a legion of people wanting to bait trend cycles for engagement or latch themselves onto a hype wave to boost reach and awareness of their products and services – and maybe attract some VC dollars, too. I call these people hype catchers – marketers that are very good at identifying trends at their early stages.

Martech and Adtech are no strangers to the same kinds of dynamics that impact buying decisions and investor portfolios. Ever heard of the DMP? How about the Salesforce NFT Cloud? What about Big Data? Remember when everyone was saying that voice assistance was the future of customer experience?

If you’re working in Martech, you’re also part of this invisible force.

A few weeks ago I touched on why the metaverse disappeared so quickly, and since then Meta is now saying they’ve discontinued NFT support in yet another shift away from the overhyped concept of the metaverse. The entire marketing technology industry went all-in on the trend, not because of careful analysis, critical introspection, and an even-handed assessment of the value of the concept, but because everyone else was getting into it, their clients were talking about it, and funds were flowing in that direction.

From TMW #113 | Abandoning the metaverse:

“During the pandemic, the idea of these kinds of platforms would be a big deal became a major narrative. At the time, Roblox was growing rapidly, at one point boasting over half of US kids on the platform, because young people were mostly in lockdowns, or avoiding social contact with others during the pandemic. But to us adults, we thought that these virtual worlds would be the future of where the next generation would prefer to spend their time. Turns out we were wrong.”

Who was at the center of metaverse hype? Some of the world’s most well-regarded consulting and advisory firms, including McKinsey, Accenture, and Deloitte. It would be a bit unfair to call these global consulting and advisory firms “hype catchers”, but I’m yet to see one correction to some of the outlandish value predictions of the metaverse, and that’s part of the problem here – hype isn’t something that reflects real-world value; instead, it’s leveraged herd mentality used to drive interest in whatever the current thing is, regardless of its fundamental value or lack thereof.

Let me ask you this: how many generative AI valuation slides have you seen recently? Are a lot of consultancies, analysis, and investment firms forecasting billions of dollars against an economy that doesn’t really exist yet? If you have, you’re seeing hype in action.

Ultimately it doesn’t matter if these firms come out and say they got metaverse predictions wrong, because no one will care. The only thing that sustains a technology movement is the hype, and hype is driven by attention, and attention is channeled into a smaller and smaller grouping of internet channels as the population of people using the internet continues to grow.

For example, 5 out of the top 10 most popular internet services are social media networks, meaning that the vast majority of our time and attention is funneled into smaller windows of information – compressed by engagement-based algorithms and limited by our own networks of connections.

Who would have thought that for most people the internet would become a tool for limiting our access to information through our own volition?

Hype pollution

Scott Galloway offers an interesting way to think about the impact of attention-driven business models on society from the standpoint of emissions.

His argument is that the attention economy creates its own type of pollution in the format of fractured discourse, increasingly violent and outrageous content, political and identity polarization which is contributing to our own diminishing attention spans, and most concerning of all, increased teenage depression.

One of the most compelling theories driving this is Noah Smith’s suggestion that it’s probably the phones. His evidence is compelling, and despite offhanded anecdotal observations from other researchers, most signs point to the advent of the iPhone and later the Android smartphones to be the main event for the changing landscape of attention. You can track the adoption of the smartphone along with the decline of teenagers who meet up with their friends every day, and an increase in mental health problems among US girls and young women around the turn of the last decade.

These trends are not exactly hype, but they do suffer from the same kinds of herd mentality patterns that are underpinned by greater social networking and groupthink on the internet. And now, we’re in a situation that appears to be unsustainable. According to the National Library of Medicine, social networks are mediating a kind of “collective attention span” that pulls people into topics on a population level, finding that over time these kinds of collective attention cycles are getting shorter and shorter.

The example of SVB is this dynamic playing out in reverse; fear and greed took control of the newsfeeds for a weekend and wrecked several banks in the process. Cancel culture also rides the waves of hype: a few misplaced words said in public or a comment from someone prominent can lead to someone losing their livelihood or a company completely collapsing.

Hype isn’t just promoting the new technology on the block; it’s a collective groupthink that drives what we care about. When applied to the Martech industry, the majority of what we care about usually isn’t genuinely helpful technology; it’s a series of hype cycles that promises much but delivers little, excites us to disappoint us, and offers a better future but ends up ushering in a worse one.

These patterns were accelerated by mobile phones and compounded by the pandemic. The story of the past three years tells this well: there’s been no other time in history that we’ve cared so much about emerging tech, just to forget it as quickly.

The hype spiral

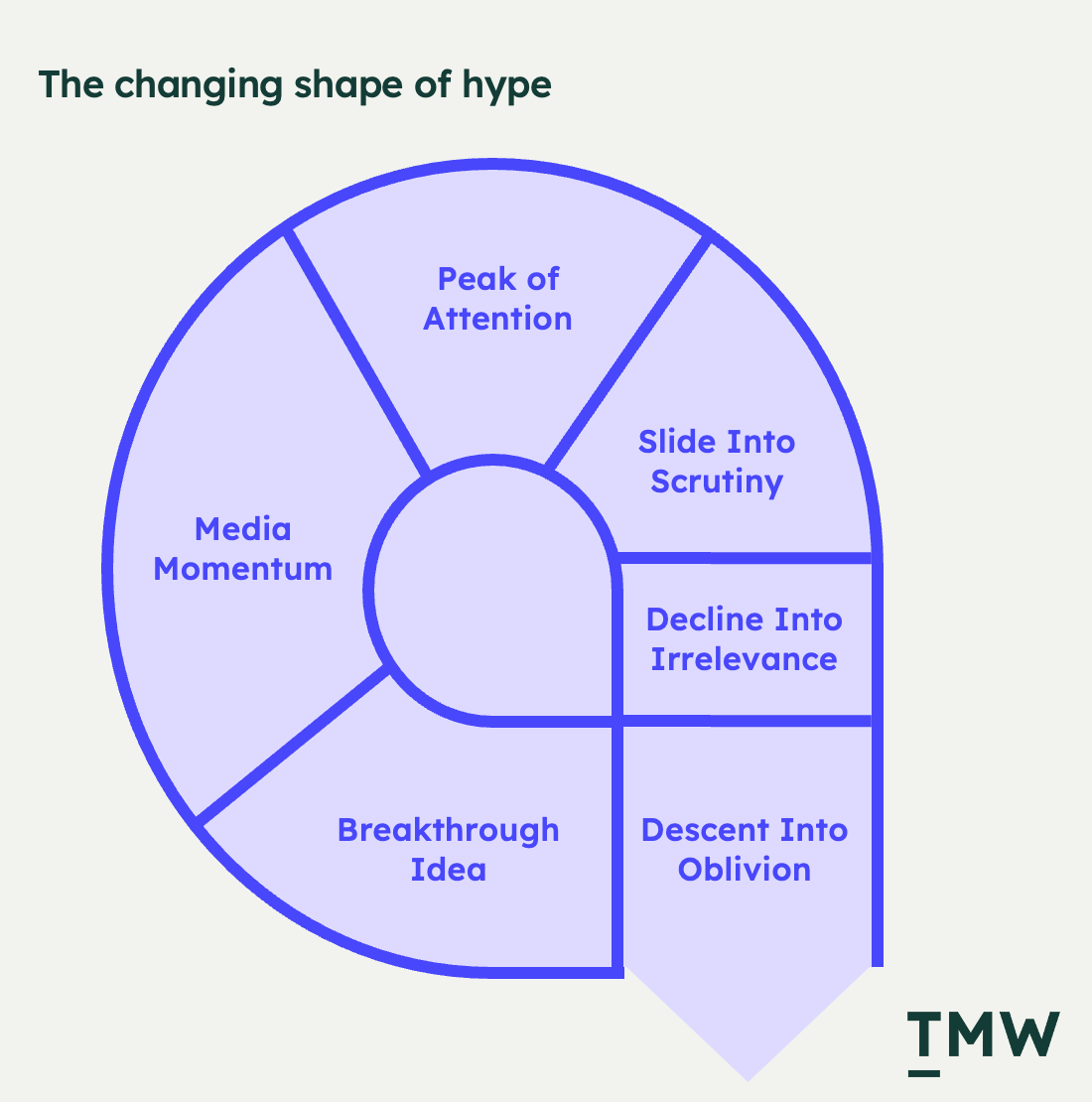

The most common mental model for understanding technology hype is the Gartner Hype Cycle. A squiggly line over a time axis showing how technologies initially get a peak of inflated expectations, a trough of disillusionment, and then flattens out to a plateau of productivity. This model has held up well over the decades and is the go-to framework for thinking about tech trends.

But in this newsfeed-driven, limited attention span-leveraging shift to a greater herd mentality, this framework is becoming less useful. For one, what we’re seeing today is not the optimistic picture the hype cycle puts forward; most of the technologies we care about today may never even out to sustainable growth – they are just falling off a cliff.

The cycle is not really a cycle anymore in a real-world sense. Instead, technology trends reflect more of a spiral structure as a new technology gains notoriety, then devolves as scrutiny against it grows, ultimately to fall into irrelevance and then to oblivion.

Is this a more pessimistic model for thinking about tech trends? Yes. Is it a more accurate reflection of the role hype plays in the technology industry today? Also yes. Take the past three years of trends and you start to see how most of the failed technology that’s gone through this cycle will never have a “plateau of productivity.”

This is because hype now exists as its own source of value. You can create very big businesses very fast with the acceleration of the internet, mobile devices, instant payments, and newsfeeds that compound a message into millions of minds in seconds. You can also see the total collapse of that business over a weekend. Take for example how tech trends over the pandemic map to the hype spiral:

A marketer’s paradise, a society’s hell

There’s something extremely valuable about harnessing hype in that it can quickly propel a brand, person or idea into the general public’s view. The velocity matters, and the ideas and messages within a hype spiral can resonate for years to come.

The problem is that it’s unpredictable. Marketers that fully leverage hype are the kinds of people who are constantly thinking about what other people are talking about. They respond quickly, are masters of the meme and can stand up an opportunity within a minute’s notice. It’s a different kind of marketing – one that allows for flexibility, freeform creativity, and a high failure rate. You also have to be extremely online.

Other marketers don’t even know or see hype until it’s already passed. But the benefit of hype is that it works as marketing without you having to do anything. The right angle focused on the right message can unknowingly propel anyone or anything to become internet famous for about fifteen minutes.

A good example of this was the juice company Ocean Spray, which came into the spotlight from a viral TikTok video during the pandemic from a guy called Doggface riding his skateboard down the street. For about two weeks during the pandemic, everyone copied this style, and even the CEO of Ocean Spray got involved in a masterful stroke of hype hijacking. Of course, no one could have predicted this. But for a marketer, this is about as close as you can get to solid gold.

But the dynamics of hype is also a powerful force that can bring out the worst in us. Hype and herd mentality can easily be manipulated to make people care about things that are in no way relevant to them, and at worse things that are not good for them. In the case of Silicon Valley Bank, it was a tragic case of waste without purpose.

At some point we will reach a limit in the marketing technology industry where it’s possible that no fundamentally helpful technology gains an audience – the only medium for growing a product will be participating or causing superficial hype spirals. The saddest thing is that we can’t do anything to really stop it – herd mentality is a learned behavior that is seemingly impossible to stop once it starts.

Hype is usually someone’s paradise and another’s hell because attention is the only thing we really have – it directs the course of our entire lives. Herd mentality on the internet depersonalizes us as social media algorithms are mechanized to harvest our attention – for good or bad. Perhaps Einstein was right?

Stay Curious,

Make sense of marketing technology.

Sign up now to get TMW delivered to your inbox every Sunday evening plus an invite to the slack community.

Want to share something interesting or be featured in The Martech Weekly? Drop me a line at juan@themartechweekly.com.