TMW #142 | Amazon’s digital sprawl

Welcome to The Martech Weekly, where every week I review some of the most interesting ideas, research, and latest news. I look to where the industry is going and what you should be paying attention to.

👋 Get TMW every Sunday

TMW is the fastest and easiest way to stay ahead of the Martech industry. Sign up to get the full version delivered every Sunday for this and every TMW, along with an invite to the TMW community. Learn more here.

Amazon’s digital sprawl

My hometown of Melbourne, Australia has one of the largest urban sprawls in the world. The area is home to 5.1 million people, but its geographical area is larger than London, which has over 10 million people. There are a bunch of reasons for this, but the main one is that everyone wants a backyard and a 3-bedroom home to call their own. The urban sprawl has created a lot of problems for infrastructure, commuting, services, and economic opportunities.

But there’s another type of sprawl, and that’s Amazon’s spread across the web. In doing so the company is gentrifying industries that have become easy targets for disruption, spreading its tentacles even further across the internet services we’ve come to rely on.

One of those areas is payments. This week, Shopify made the news that they’ve accepted Amazon’s offer to allow their merchants to install the Amazon “Buy Button” on Shopify-hosted websites. The offer was initially refused by Shopify because of its competitive threat to their business, warning merchants that using it would be in breach of their terms of service.

So there’s a bit of an about-face here. With their official launch website saying that the decision to revert back from their earlier position is in the best interests of their merchants, it’s a curious maneuver, because you could argue that it does exactly the opposite.

“We’re on a mission to make commerce better for everyone. That means making sure our merchants are able to sell everywhere. To do this, we’re committed to giving our merchants and their customers more choice”

In the launch video, they outline a few key features. The “Buy with Prime” buttons allow customers to use their Amazon account as a payment method, and help them access Prime free delivery if the merchant is already selling on Amazon.

Merchants get access to Prime customer data, and can manage Amazon deliveries in their Shopify admin. However, it’s unclear to what extent and what kinds of data the merchants get from a transaction. For example, existing Amazon merchants don’t even receive an email address from the customers who buy from them.

Enabling this feature on Shopify sites could spell disaster for the marketing efforts of Shopify-enabled e-commerce brands, especially if vital data points like email addresses are not included in that data transfer.

In exchange, Amazon claims that the “Buy with Prime” button increases conversion by 25% based on their own testing. And there’s some logic to that: Amazon has high consumer trust when it comes to deliveries and returns. Risking your delivery that is managed by an unknown merchant doesn’t make a lot of sense if you can get Amazon to do it from the consumer’s point of view.

But the biggest challenge with Shopify letting Amazon into its ecosystem is that it could turn Shopify merchants into just another interface for Amazon. Let me explain:

Shopify’s gentrification

Currently, there’s a dividing wall between Amazon and Shopify. I look at the two companies as the extreme polar opposites of how e-commerce can be done online; they present two very different outlooks on e-commerce and online shopping.

Amazon is the centralized behemoth where everything needs to live under its logo, but its ruthless optimization and standardizing of the customer experience means they are often preferred.

Shopify is completely different. By allowing merchants to have their own place online and only providing the infrastructure and tools, they sacrifice efficiency and standardized experiences to enable merchants to build their own unique expressions of online shopping, fulfillment, and retention. And it seems to be working; Shopify did $197 billion in GMV in 2022, which is still less than half of Amazon’s massive $514 billion in sales last year. But it’s still nothing to sniff at.

Right now, Amazon and Shopify are separated by platform and e-commerce philosophies. One is centralized and only allows FBA (Fulfillment by Amazon) or FBM (Fulfillment by Merchant) types, while Shopify allows limitless variations of merchant setup on their platform:

By crossing the line, the “Buy with Prime” button opens up a cross-sectional infiltration of merchant and Shopify operations:

The first type is the logistical transfer. Every merchant knows that deliveries and returns are a huge part of their customer’s experience, and those using the new Amazon button will literally be outsourcing that bit to Amazon. There’s very little control from here, and merchants would need to adhere to Amazon’s rules around refunds and returns. The customer benefit means free shipping and not having to buy on Amazon to do it. While Shopify promises merchants that they can view their Amazon delivery operations in the Shopify app, it’s unclear exactly what kinds of information will be provided back to them.

The second transfer is the data aspect. There’s scant detail as to what data the merchant gets and what Shopify collects in aggregate. But this is what it looks like:

And this is what it looks like in a complete scenario:

You have to ask yourself the question: What’s really left here for Shopify when so much of the infrastructure is handled by Amazon? A pretty-looking website? Maybe a few extra product photos in a gallery? This is why I call the move Shopify’s gentrification – Amazon is moving in and hollowing out Shopify, and replacing it with its own infrastructure.

This also comes at a time when, earlier this year, Shopify sold its logistics business to Flexport, because the company was focusing on too many verticals in its business. Clearly, Shopify has lost the infrastructure battle with Amazon. Raise the white flag.

Amazon has a long history of squeezing merchants on their prices, not allowing competing prices outside of its platform, and delisting merchants that don’t fully adhere to its rules. This seems at odds with Shopify’s decentralized vision for online e-commerce.

But what appears the most strange to me is that Shopify would accept such a competitive threat to their core infrastructure business and their hundreds of app store partners that have built payments, logistics, and shipping businesses around the Shopify ecosystem. Yet, even the market saw it as an initially positive signal. Could this be the deal that puts Shopify on a sidelined trajectory? It seems as though this could be the case, and we hate to see it. I was rooting for you, Shopify! Why!?

Breaking out the four walls

The bigger story here is not the “Buy with Prime” button; it’s Amazon’s attempt to break out of its own ecosystem to collect more customer data.

The decision by Amazon to start expanding its transactional technology outside of its four walls is worth mentioning because it’s not the only attempt to go beyond its ecosystem. Amazon also recently decided that it’s going to offer programmatic technology to run ads for publishers outside of its ecosystem.

The final frontiers for Amazon on the internet are payments and advertising. It’s the last high-leverage, high-margin, and scalable domains of online technology. So, it makes sense for Amazon to embrace these two relatively untouched domains. But it also raises an interesting question for the company: Why?

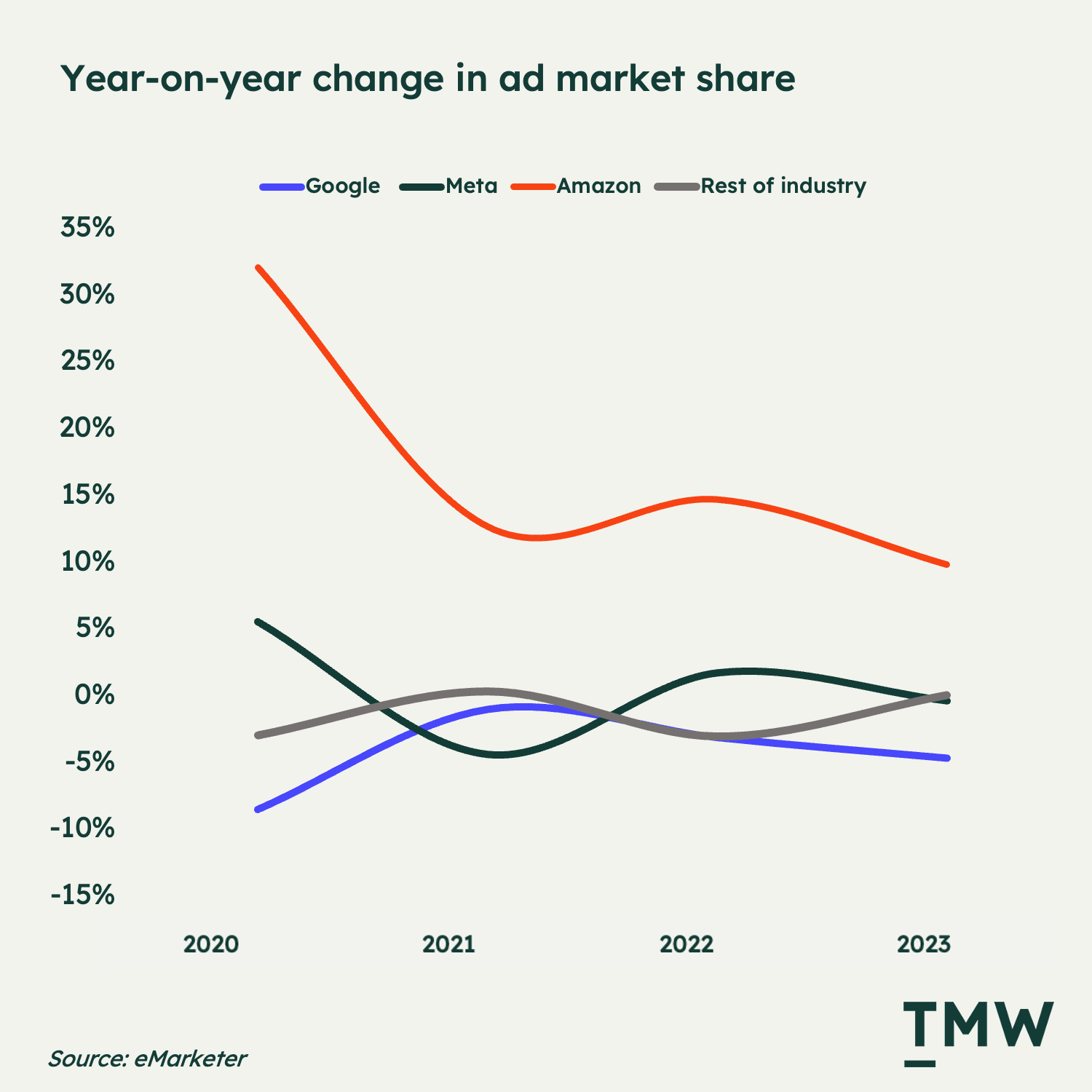

It’s becoming clearer that by the looks of Amazon’s business strategy, focusing on its own ecosystem will create diminishing returns. Advertising is already a huge business for Amazon, bringing in $38 billion in revenue in 2022 and growing its ad market share by 17% on average over the past four years. Amazon’s ad revenue is $100 per customer and $20k per employee. It’s the fastest-growing ad network right now, faster than Meta, Google, and the rest of the online advertising industry.

Transactional leverage gives Amazon advertising advantages. The company’s rising fortunes in advertising are borne out of the push to privacy across the advertising industry, which is creating a ripe opportunity for platforms that are rich in first-party data to monetize their surfaces. From TMW #137 | Ad networks are everywhere:

“Elysium is my go-to illustration to describe the pressures and shifts as the web becomes more privatized. In the movie, the tension is all in the two different societies. The space society where the 1% live, and the society on earth that live in pollution and poverty. The open programmatic web is the 99%, filled with Made-For-Advertising (MFA) websites, conspiracy platforms, fake news, “churnalism,” and an endless sewer of UGC. This is the open web, where mayhem rules.”

Amazon is one of the most premium sources of first-party data on the internet. But what happens with large platforms like Amazon is that consumer and advertiser fatigue can set in if their walled garden user base is not exponentially growing with the number of ads they are served, showing diminishing returns and an increasingly frustrated user base.

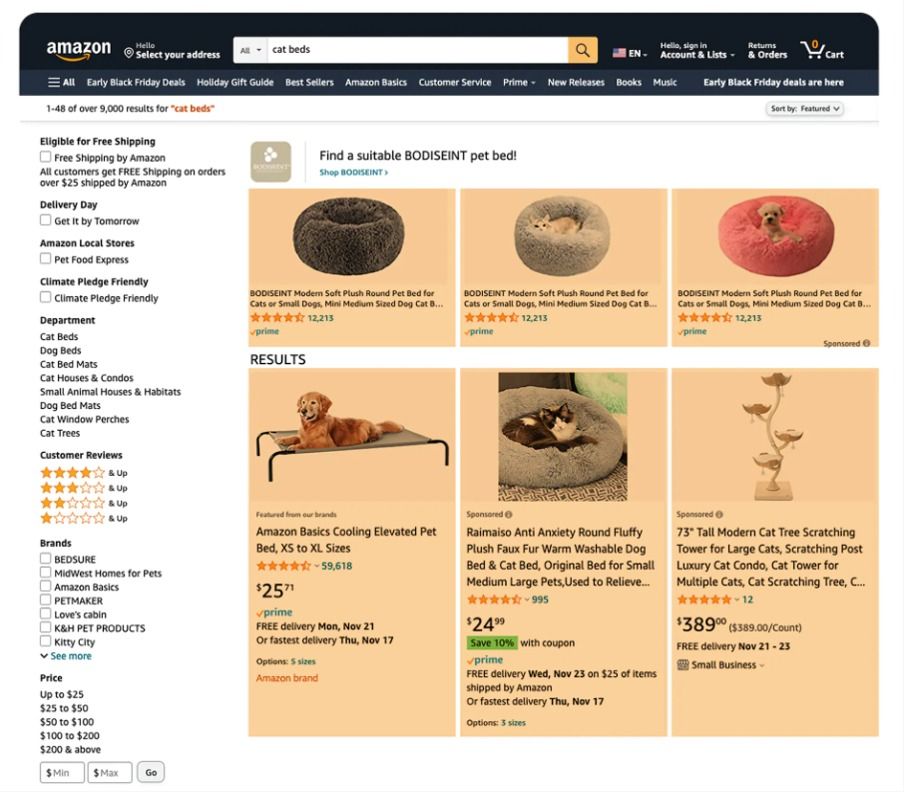

The Washington Post did a fascinating review of this problem. Searching “cat beds” gives sponsored products four out of six results for a user. This will increasingly frustrate users as their shopping experience is increasingly invaded by ads. Which of these are sponsored ads? You might need to pull out a magnifying glass.

This is the beauty of Social and Search: as long as there are users on the internet, they have limitless opportunities to serve ads to evergreen audiences, and advertising is less intrusive because it’s not yet in the shopping experience – it’s all the content you consume before you get to a point of purchase.

People go to Amazon to shop. That’s why the company needs to increasingly grow its sprawl across other publishers. Transactional data and off-site ad impressions appear to be the big value drivers for a company running out of humans to monetize.

What an interesting conundrum.

It’s always about ads

You might suspect that Amazon’s reach into offsite transactions with the “Buy with Prime” button has nothing to do with its ad business. But they are very much linked. The land grab for transactional infrastructure is about data collection, and the most important data for advertising is where and what people buy. When people use the Amazon “Buy with Prime” button, it’s collecting data that creates a competitive moat for Amazon.

The largest platforms that can offer enriched targeting based on first-party data have a huge advantage. Amazon is “going underground” in a way to collect data on consumers. Collecting consumer data through transactions to push to offsite advertising doesn’t seem so obvious, but it is an absolutely huge opportunity to strengthen Amazon’s ad network. By displaying ads in third-party publishers, this creates a bigger circle to run ads.

This might be the alternative to third-party cookies that most of us are missing: large, influential tech platforms launching features across the web that collect data to reinforce their own ad networks. We now have Apple Pay, Google Pay, PayPal, a smattering of “buy now pay later” options, Alipay, and others – all of them collecting their own transactional data. How could Amazon not enter this market?

Attentional and behavioral data is valuable, and the email address or the phone number is the core of identity, but by far, the data point that makes it all valuable to advertisers – for targeting and for analytics – is the conversion and the spend. Without third-party cookies, Amazon offers an interesting alternative: run programmatic ads on its platform, with targeting from all the users that are transacting inside and outside of Amazon.

It's not a bad value proposition. This is how Amazon’s value proposition for ads is framed in the media:

“In an age where third-party cookies are headed for extinction, access to quality first-party data is critical. If you’ve made a purchase on Amazon, you voluntarily told them where you live, what you like to buy, and what things interest you. This first-party data enables publishers to serve more relevant ads to its users. More relevant ads lead to higher conversion for advertisers, which enable publishers to charge them more to serve their ads.”

So it’s no surprise really that the “Buy with Prime” button should be considered as a thinly veiled data collection operation. But it’s also a privacy nightmare. Do consumers really want Amazon tracking their transactions across the web? I guess they can use another payment option or their credit card. But if we can learn anything from history, it’s that Amazon has staked its success on convenience, and it’s no different here. To most people, the tradeoff between privacy and using Prime on other websites is no tradeoff at all.

The digital sprawl

If you’ve ever spent time in Melbourne, you know how much the urban sprawl has a chokehold over the city. Like Los Angeles, It’s impossible to get anywhere. But yet again, this is a result of a lack of urban planning and infrastructure.

The internet is no different. The digital sprawl consists of a lack of regulatory oversight and planning for the boundaries of what companies can and can’t do on the web. Amazon can go right ahead and partner with Shopify with the “Buy with Prime” initiative, strengthen its market presence and its ad networks, and there’s really nothing that can be done to stop it.

In Amazon’s case, its increased influence over the web in new domains means that the company will be continuing to influence shopping, browsing and content consumption to drive revenue.

There’s never been a machine that turns bits and atoms into revenue so efficiently as Amazon, and for Shopify, it seems as though it’s too late for the company to become a real infrastructure competitor for independent merchants.

In other words, they’ve let the fox in the hen house.

Stay Curious,

Make sense of marketing technology.

Sign up now to get TMW delivered to your inbox every Sunday evening plus an invite to the slack community.

Want to share something interesting or be featured in The Martech Weekly? Drop me a line at juan@themartechweekly.com.