TMW #148 | Europe’s digital catch-22

Welcome to The Martech Weekly, where every week I review some of the most interesting ideas, research, and latest news. I look to where the industry is going and what you should be paying attention to.

👋 Get TMW every Sunday

TMW is the fastest and easiest way to stay ahead of the Martech industry. Sign up to get the full version delivered every Sunday for this and every TMW, along with an invite to the TMW community. Learn more here.

Europe’s digital catch-22

“They're trying to kill me," Yossarian told him calmly. “No one's trying to kill you," Clevinger cried. “Then why are they shooting at me?" Yossarian asked. “They're shooting at everyone," Clevinger answered. "They're trying to kill everyone." “And what difference does that make?”

Joseph Heller, Catch-22

Recently, Meta agreed to the EU’s new Digital Markets Act (DMA) terms that it will provide an ad-free option for users of Facebook and Instagram. This strikes me as the stupidest idea that’s ever crossed my desk, and trust me, I’ve seen a lot of dumb ideas.

But this is just one domino in a long line of privacy, competition, and anti-trust actions from the European government over the past seven years, and perhaps a culmination of Europe’s ultimate goal to regulate the internet. But where does this put a region with a population of more than double the size of the United States, where major social media and search platforms rely on billions of dollars of ad revenue?

I haven’t seen any good answers. But here’s my posit. The ongoing litigation from the European government could put the region into a tricky bind; cutting off online data flows from platforms and companies means a disconnect from the global economy and fewer opportunities for marketers to grow brands. But allowing monopolistic platforms to run free hurts innovation and startups. It’s the catch-22 of this decade, or what the Europe Commission calls “The Digital Decade” – a long-term plan to clean up the web from a privacy, competition, and safety standpoint.

So will these changes lead to Europe’s digital decline, or will the region become a shining beacon of hope and a promised land of new innovation, startup development, and powerful growth opportunities for marketers?

The regulator

The nerd in me wants Martin Scorsese to direct a movie about the past ten years of European digital regulation. I would call it THE REGULATOR. It would be a thrilling tale of political bravery and destruction. A Few Good Men meets Big Short meets The Terminator. Err… something like that.

While regulation can be a super dry topic, the European Commission and the GDPR have become world renowned for their innovation in regulating data collection, sharing, and increasingly policing large online platforms. They have been the single dominant force and the closest we have to what a regulated internet could look like, completely changing the global marketing technology industry from the standpoint of consent and data collection. They’ve handed out billions in privacy fines and have exposed the many privacy and surveillance problems with RTB, AdTech, and cross-country data storage from Europe to other countries like the United States.

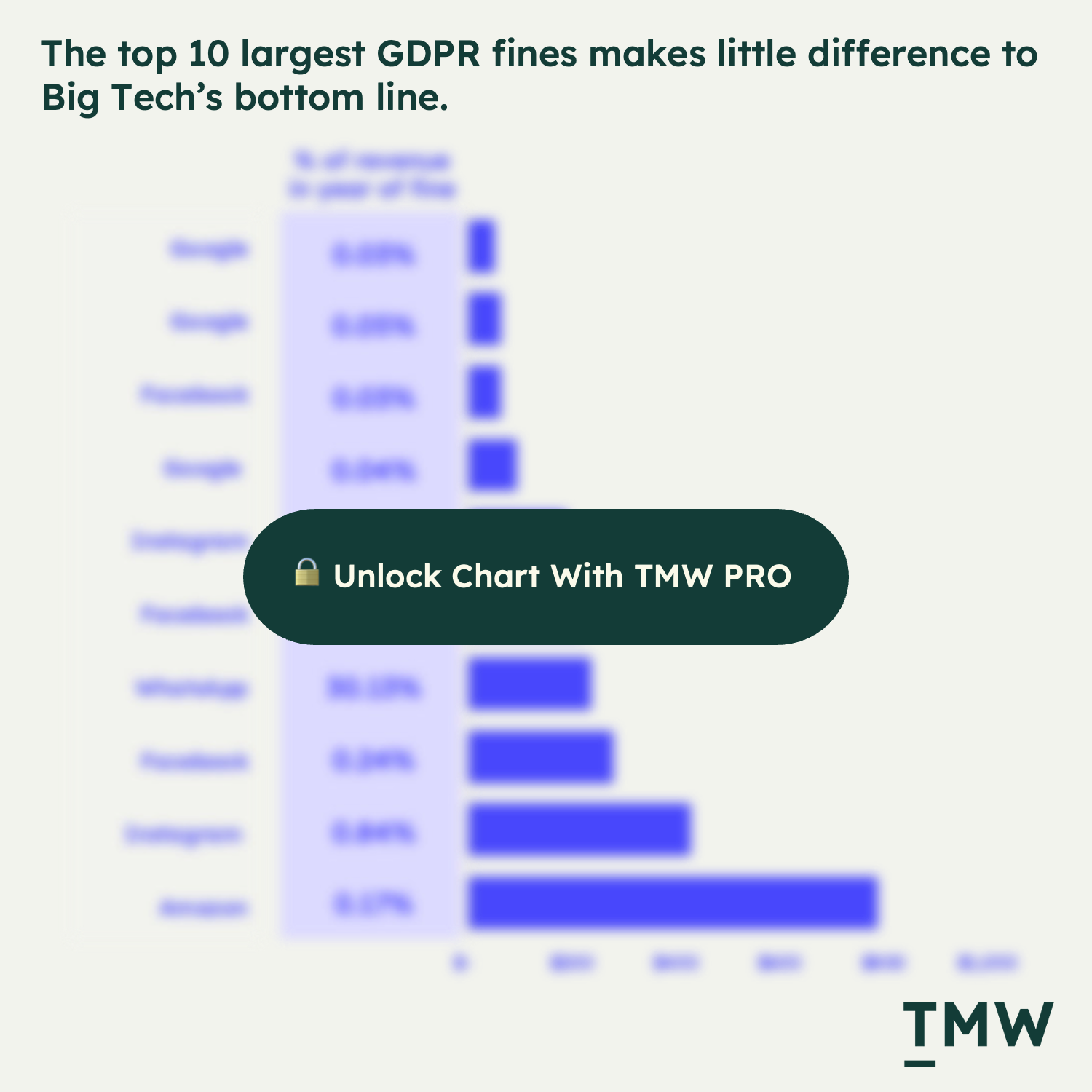

Yet even if the GDPR is registering billions in fines, it makes barely a dent in the profits of the companies that are benefiting the most from breaking data privacy legislation laws. Jeff Bezos has famously said, “Your margin is my opportunity.” Well in this case, the ability to withstand GDPR fines is the Big Tech’s opportunity.

Enter the newly created Digital Services Act (DSA) and Digital Markets Act (DMA). These landmark rulings by the EU Commission have been released this year in an effort not just to regulate on the data collected by massive platforms, but also on what they can and can’t do with their platforms with European citizens.

The two acts were passed into law unanimously, and only took a year to go from a concept to a fully-fledged piece of enforceable legislation. Meta is one of the first companies to interact directly with it, as the EU Commission is forcing the company to offer an ad-free version – the first time that any large social media platform has been forced to do so. Imagine for a minute asking any other business to make a decision that cuts off revenue. The EU is doing that.

According to the DSA, the European government seeks to safeguard users from the adverse effects of social media, search, and marketplace platforms, what they call VLOPs – “very large online platforms.” Here are the criteria for what it constitutes:

Under the DSA, platforms will not only have to be more transparent, but will also be held accountable for their role in disseminating illegal and harmful content. Amongst other things, the DSA:

- lays down special obligations for online marketplaces in order to combat the online sale of illegal products and services;

- introduces measures to counter illegal content online and obligations for platforms to react quickly, while respecting fundamental rights;

- better protects minors online by prohibiting platforms from using targeted advertising based on the use of minors' personal data as defined in EU law;

- imposes certain limits on the presentation of advertising and on the use of sensitive personal data for targeted advertising, including gender, race and religion;

- bans misleading interfaces known as 'dark patterns' and practices aimed at misleading

The second to last item there is the one that’s hurting Big Tech the most, and its impact can be felt in the business models. Forcing Meta to offer an ad-free option, limiting data for targeted advertising, and the scope of what you can use to advertise makes the EU not a great place to operate advertising products.

While the DSA protects consumers from the potential harms of online platforms, on the other side of the fence, the DMA seeks to protect businesses:

The Digital Markets Regulation focuses on ensuring a level playing field for all digital entrepreneurs, regardless of their size. The purpose of the Digital Markets Regulation is to ensure a competitive and fair digital sector by doing the following:

- unfair practices of digital platforms with the largest market share are prohibited

- business users are given the opportunity to offer more choices to consumers

- better services and fairer prices are guaranteed to consumers

- clear rights and obligations are established for large digital platforms

- innovation and the creation of a fairer digital platform environment for technology start-ups are promoted

And most interesting to the DMA is their treatment of what they call “access controllers” – private companies that have an oversized influence on how society uses the internet. These can be online marketplaces or app stores, search engines, social networking, cloud storage, advertising, and Adtech platforms. The rules of both the DMA and the DSA are applied differently to large platforms than to small, which seeks to slow down growth in Europe so that other market entrants can compete.

Companies that fall into an access controller or VLOP category face much bigger fines for lack of compliance: 10 to 20% of global turnover, as well as government intervention in operations if breaches of the law persist. Access controllers especially face a big shift in what is expected of them from Europe: they must be able to offer the user choice in what software they use in each operating system, which impacts things like Apple’s closed App Store, forcing the company to allow users to download apps directly from the web for the first time or allow other app stores on its device.

It will also exert more pressure to remove subscription tactics by providing guidelines to how platforms should present the option to unsubscribe (similar to the current FCC case against Amazon’s dark patterns) from their platform and ensure that apps, messaging services, devices (hello USB C) and data can be interoperable between platforms.

Clearly this is a huge correction for the digital economy, and unprecedented in how much large online platforms, device makers and OS platforms will need to change under it if they want to access European consumers.

No wonder they are setting the template for other governments to follow in places like Australia and California when tackling online monopolies and digital privacy. But should it really be that? The EU, in its crusade to regulate the internet, may end up with a lack of foreign digital investment and fewer options for companies to invest in growth both locally and abroad, which ultimately ladders up to a shrinking economy.

With the combination of GDPR, DMA and DSA, Europe is disinviting the growth of major global platforms. But you’ve got to admit, the way they are standing up to internet monopolies is pretty badass, amirite?

A prison for platforms

Some of the rules proposed for large online platforms are just plain dumb. The last rule I mentioned about interoperability has so many flaws that it’s technically impossible, as Ben Evans explains:

“To give another EU example (because that’s where most of the laws are coming from right now) the initial drafts of the DMA required anyone running a messaging app to let ‘any’ third party interconnect and interoperate, and to give any such third party ‘all’ the same access to internal data as internal teams. That sounds sensible… until you realize that hundreds of groups are trying to connect to WhatsApp or iMessage to spam their users, and you’ve just told Meta and Apple to let them do that, and that dozens of intelligence agencies would love to have ‘all the data your internal teams have’. Fortunately, in this case, when the entire tech industry said ‘you’re out of your mind’ the EU did actually listen.”

This is just one example, but it paints the picture well. Not all rules can be followed, and sometimes it creates adverse situations, especially for marketers.

It must not be fun doing digital marketing for an EU company in the EU. The amount of work required to vet every ad platform for any privacy violation, having to implement those godawful cookie banners, and facing a marketplace with less data for targeted advertising and personalization makes the marketer’s job much harder. With the DSA and DMA now in place, well, there are even more constraints to what Google and Meta can offer marketers, which means more to learn and tweak.

But if Europe becomes a prison for platforms it will mean restricting access, movement, innovation and change. About 10% of Meta’s ad revenue comes from Europe (excluding the UK), which amounts to billions of dollars each year. That’s high-stakes money. But as Ben Thompson argues, the EU has low annual revenue per user, which gives rise to the idea that Europe is not that important to Meta, so it’s not a major issue if EU regulators make operating Meta harder.

And when you look at the overall share of ad revenue from Meta by region, you can see that Europe and the UK have decreased slightly over the years, about as much as the United States, while APAC and ROW continue to grow. In other words: The west has been conquered.

Google shows a similar trend of an ongoing decrease in total revenue from their reporting group of the EU and the Middle East (EMEA):

So for Europe, both major online platforms for marketers are shrinking. Not by a lot, but a percentage point either way means tens or hundreds of millions of dollars annually. And this is likely to only get worse as the DMA and DSA roll out.

Here’s my back-of-the-napkin math of what this does to companies. Harsher conditions and lessening online channel effectiveness will attract fewer marketers. Fewer skilled marketers driving growth and revenue will mean that EU companies will struggle to grow. This equates to a negative cycle of less overall growth for brands, and fewer startups building and growing out of Europe.

Forcing Apple to make another app store (and by doing so, lowering their standards and ease of use), making Meta offer a free version, and ensuring that Google can’t use US data centers for products like Google Analytics, are all huge disincentives for connecting Europe to the global online growth machine.

But I do think that there is an alternative reality when it comes to Europe’s outlook.

The two faces of EU regulatory transformation

The problem EU regulators have on their hands is that in the new digital and global economy, there is a tension between safeguarding citizen privacy and enabling companies to use these tools to drive growth and compete in a marketplace where the majority of ad revenue is going to digital platforms The harsh reality of privacy regulation is that it will limit the ability and use of customer data. But the sad truth is that this growth comes at the cost of consumer privacy. Which one is better for society?

This is the hardest question to answer, and one that will persist for a long time.

But the changes so far have been mostly positive. Without the EU GDPR, we would have never understood the amount of privacy violations that would have otherwise gone undetected. Consent from consumers – even if it depresses the volume of data you can collect – is an overall good thing. Acceptance rates of cookie opt-ins are the lowest in the western world, which tells me that people want to control their data collection and preferences.

The EU GDPR pioneered this paradigm change to value giving consumers a say in what happens to their data. But so much of the privacy hysteria is overblown. Online platforms are not surveilling consumers; they are collecting data on people to use in aggregate to offer advertising tools.

Even the monopoly deterrence implemented by Europe do good things for stemming the control large online platforms have over internet data. Even if the EU is taking an activist approach at times to internet platforms and data regulation, the US and Asia aren’t doing much yet in terms of formal, guidelines. The EU is leading the charge of creating a more fair and balanced internet landscape.

The DMA and the DSA are the countervailing forces of the GDPR. Yes, marketers will have less access to data to grow their companies. And yes, competition and platform regulation make internet startups more feasible. Both regulations are positioned to ensure that more companies can enter the European market and do what Google, Apple, Meta and Amazon can do. Which should be something to celebrate – these companies should not be eternally fixed at the top of the internet food chain.

It’s for this reason the EU is becoming the foundation for other world governments such as the United States and Australia, purely because the EU has more experience now in real, active litigation and implantation of privacy controls. Jozef Síkela, Minister for Industry and Trade of the Czech Republic, explains:

“The Digital Services Act is one of the EU's most ground-breaking horizontal regulations and I am convinced it has the potential to become the 'gold standard' for other regulators in the world. By setting new standards for a safer and more accountable online environment, the DSA marks the beginning of a new relationship between online platforms and users and regulators in the European Union and beyond.”

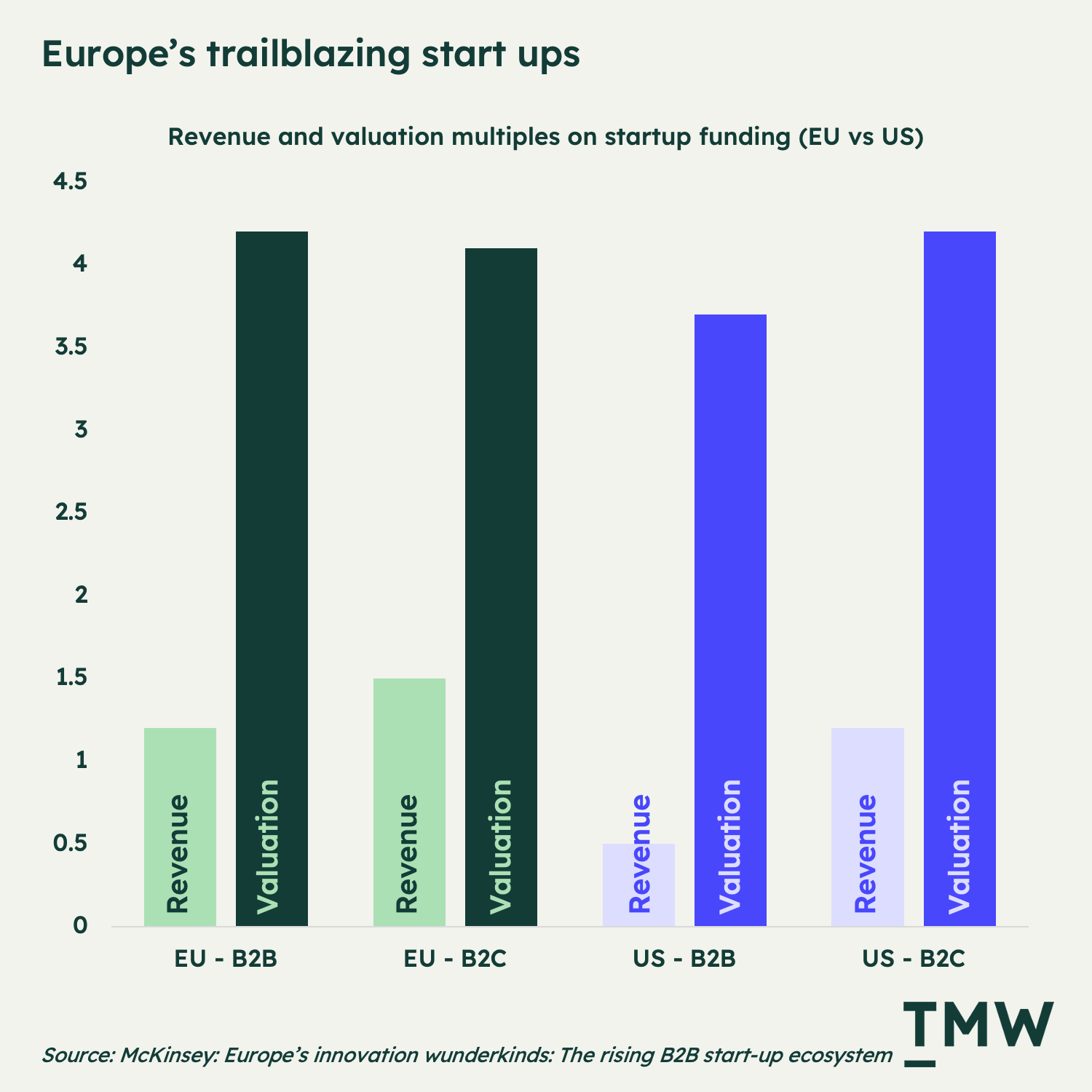

And when it comes to tech startups in Europe, venture funding doubled last year, growing much faster than in the United States. Last year, Europe minted more billion-dollar valued companies than anywhere else on earth, and the valuation of those companies on revenue and valuation exceeds the United States – and in some cases, doubles it.

So perhaps we’re seeing the emergence of a new era of startup internet platforms that can compete with US Big Tech. After all, Europe gave us Spotify; why can’t it give us a better search engine, or social media platforms?

Maybe, just maybe, Europe could be the next catalyzing region for internet innovation. And for marketers on the ground floor of these new companies starting up with EU backing, competing with Big Tech might actually shift from being a pipe dream to becoming a viable reality. But it’s still a catch-22. Innovation requires data, and GDPR data rules make it difficult to see any such growth in the near term.

Europe can’t be the world leader in GDP growth or in marketing technology and advertising tech development without establishing some degree of harmonization. Cut off data and cut off the platforms, and you’re in for a long wait for EU native companies to come and build what’s already been done. The real question with Europe’s catch-22 is if it can successfully do both and still thrive.

Stay Curious,

Make sense of marketing technology.

Sign up now to get TMW delivered to your inbox every Sunday evening plus an invite to the slack community.

Want to share something interesting or be featured in The Martech Weekly? Drop me a line at juan@themartechweekly.com.