TMW #141 | The content cold war

Welcome to The Martech Weekly, where every week I review some of the most interesting ideas, research, and latest news. I look to where the industry is going and what you should be paying attention to.

👋 Get TMW every Sunday

TMW is the fastest and easiest way to stay ahead of the Martech industry. Sign up to get the full version delivered every Sunday for this and every TMW, along with an invite to the TMW community. Learn more here.

The content cold war

In 2023, one of the worst things that can happen to you on the internet is going viral. And one of the worst places to go viral is on X/Twitter, in what’s known as the “main character effect.” Ryan Broderick, the author of the hilariously fun newsletter Garbage Day, explains why:

“The main character effect isn’t unique to Twitter. It happens on Tumblr, on Reddit, probably on Pinterest? But the speed and ferocity and, most importantly, the irl impact of becoming a main character on Twitter is unparalleled. Caught the attention of an angry mob on Tumblr? Maybe avoid Hot Topic’s and Twenty One Pilot shows for a while. Caught the attention of Twitter? You’ll absolutely end up with a New York Post article (or multiple) being written about you at the bare minimum. You’ll also almost certainly lose your job — though, you may end up with a better one. It’s a real crapshoot.”

As one X/Twitter user once said, “Each day on twitter there is one main character. The goal is to never be it.” And this, dear reader, is sage advice.

The whole idea of virality is only a 15 to 20-year-old phenomenon, and it’s entirely made possible by social media platforms that are supercharged by algorithmic newsfeeds. The machines that influence, moderate, and process information flows have been so finely tuned by algorithms that they create all kinds of weird situations on the web, including going viral.

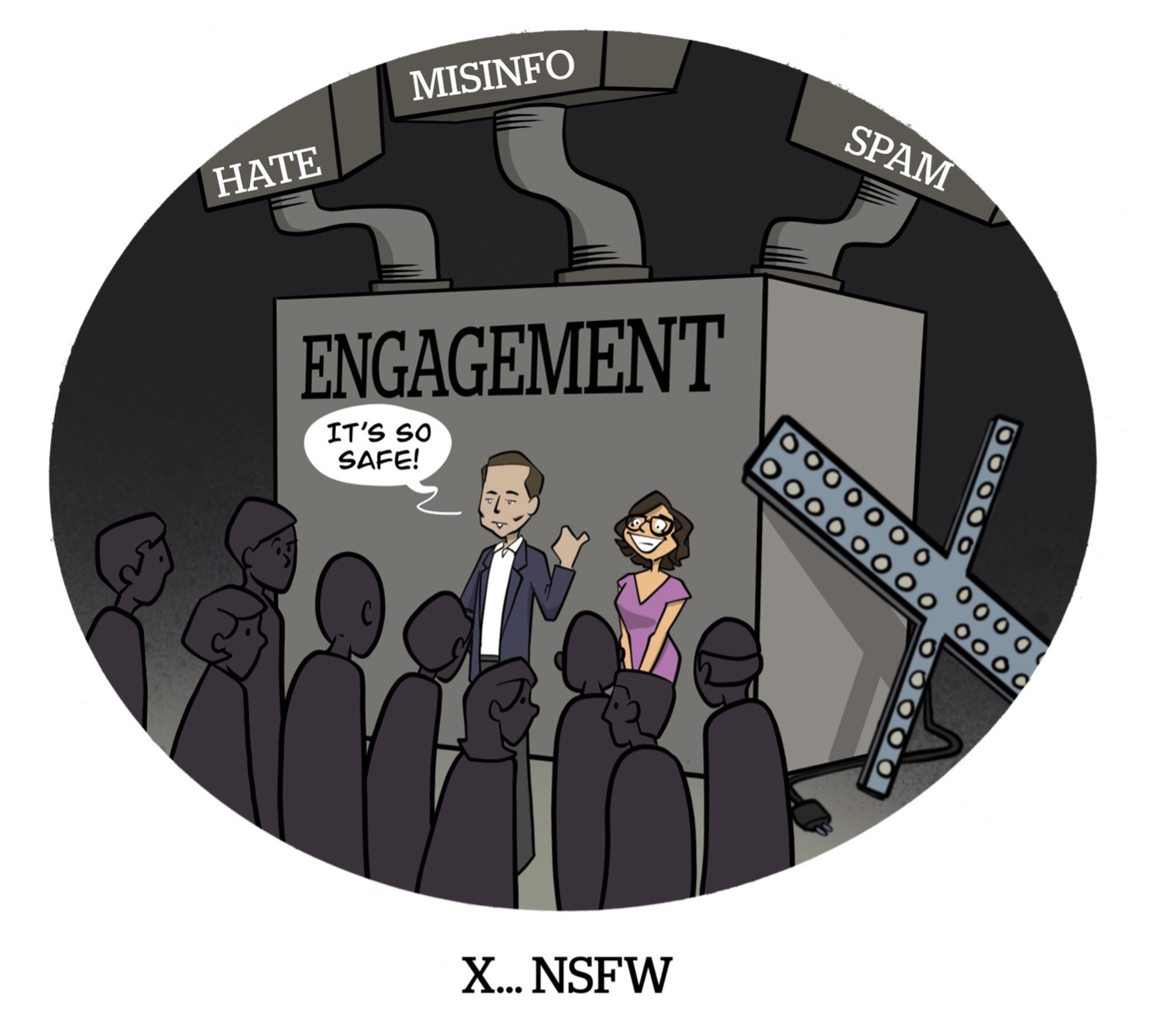

The ongoing concern is that these algorithms are optimized to direct our attention to things that benefit the corporations behind them, specifically time on site, engagement, and whether or not we click on ads. In other words, the goal of platforms like X/Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Tumblr, and even Google, is that the best experience for their users is if – as Neil Postman suggests – we’re “entertaining ourselves to death.”

It's been at least a good 15 years now of this new algorithmic experiment where we’ve slowly replaced institutions and large swaths of the entertainment industry with social media and online content platforms. And while it’s played a huge role in democratizing growth and opportunity by allowing businesses of all shapes and sizes to grow through paid ads and keeping the internet free for billions of people, I think that from an ethics and societal health standpoint, the experiment has largely failed.

We’re now entering what I call the content cold war: a tumultuous period where the adverse effects of social media are overwhelming us, distracting our minds, depressing our teens, making democratic elections significantly harder to maintain, disenfranchising intellectual discourse, and turning a generation of people into distracted, attention seeking growth hackers.

A turning point is coming, because the situation that giant search and social platforms have created is unsustainable.

The algorithmic society

Spend some time in Myanmar to see the “benefits” of Facebook and Instagram on their society, or read this report suggesting that most of our internet platforms are “completely awash in pro-Beijing content being inauthentically posted by groups linked to the Chinese government,” and you’ll see what I mean by the problems caused by widespread access to social platforms fine-tuned to outrage us and get us clicking.

It’s not only political problems or misinformation. The UK NSPCC came out with new research that incidents of online child grooming using social media networks like Snapchat and Meta have risen by 82% over the past five years. Most of the incidents are against girls, with 25% against primary-aged kids.

To research this essay, I spent a bit of time on TikTok, and what immediately struck me after spending only 10 minutes scrolling on the app was how shallow and frivolous all the content is on there. And some of the viral trends such as the “NPC livestream” where people pay money to control the actions of online influencers and the borderline child abuse trend of parents “cracking eggs on kid’s faces” to which the children appear visibly hurt and shocked.

I have to agree with Amy Kean when she asks the question:

“Smacking your kid in the face for LOLs and a million views definitely feels like a final straw for a digital population out of ideas, resorting to low level violence, just to be seen.

What have we become?”

TikTok is an entire galaxy of this kind of stuff. You have your typical engagement hacking content, internet drama, and the occasional educational video, but most of it is a perfect picture of what happens when you build a social algorithm that rewards viral growth tactics and user engagement from Instagram’s and Snapchat’s worst users. You get a chumbucket of pure algorithmic sludge, awash with intellectual fast food selecting on novelty and reactions.

I’ve personally been blocking as many viral content, meme, misinformation, political outrage, and Andrew Tate fan accounts as possible that have come to dominate X/Twitter over the past months. My goal is to have better connections with people working in media, marketing and tech – and that’s valuable – but you have to work for a semblance of a connection in a social experience that wants to distract and entertain you more than anything else.

Adam Singer’s recent essay on the problem these social media networks pose for actual discourse and intellectual engagement summarizes the situation quite well:

“For a long time we were in a full on bear market here, wherein stream-based social platforms more interested in having users chase dopamine hits and slot-machine style attention payouts for sharing ever more-controversial and risqué takes were peaking. Many were rewarded with large audiences purely for being the most polarized and the least civil while sharing ideas, discussing news of the day and debating topics large and small, whether industry-specific or national/international. Most of the best people who started these platforms were well intentioned and at least present. Now it seems like few are left who actually care about content quality and what behavior is rewarded.”

You have to wonder about the product teams behind these social apps. Clearly, we have a problem with both algorithmic spam and the people who are finding ways to manipulate it for their own gain. It’s either that these massive companies have become too big, too siloed, and too slow to address the problems on these apps or that, as Singer suggests, product managers are just asleep at the wheel - too focused on quarterly engagement and growth OKRs to see what their choices are doing to the real communities that are being influenced by these social networks. Either way, the manner in which these social networks are designed for a certain kind of optimization is becoming increasingly adversarial for regular users.

The question you need to ask is whether or not giving your time and attention to these platforms is really worth it. I mean, do we really want to live in a world where we’re getting increasingly distracted, forced into filter bubbles, creating online cults, and where child exploitation and abuse run rampant? Where the people making the design choices don’t really care about degrading the experience of their users as long as it brings in greater engagement?

Surely there must be an offramp.

Rage against the algorithm

This essay works as a bookend for the past two essays about generative AI: TMW #139 | The long tail of generative AI and TMW #140 | AI and the channel (r)evolution. And there’s something I’ve been alluding to in those two essays that need further investigation: generative AI allows content creation to become cheaper, faster and more accessible, it could lead to an unintended consequence of people valuing traditional media, non-algorithmic online alternatives like forums and blogs, and the brands that have real humans creating content and providing information. In other words, perhaps it’s time to rage against the algorithm?

We’ve crossed the Rubicon of behavior-modifying algorithms that either turn you into a virality-optimized memelord, a banal LinkedIn “top voice,” or an attention-seeking Instagram micro-influencer. Downgrading posts because it has an external link, or arbitrarily policing speech, or just outright allowing misinformation to grow, is just the norm on most of these platforms.

This is the content cold war. Generative AI will turn our newsfeeds and inboxes into pure algorithmically-generated sewage, causing creators to revolt, and return to channels and outlets that can be trusted, with the internet’s user base becoming increasingly divided by the “premium” and the “freemium.” And if you can afford premium subscriptions, you’ll get to hear from a real human who will do primary research and offer genuine expressions of human creativity. For everyone else, they’ll get to live in a content slum filled with dopamine-hacking newsfeeds, misinformation, AI-generated gibberish, outrage porn, and the thoughts of vacuous celebrities like Jordan Peterson, Dylan Mulvaney, and Andrew Tate.

Molded by the machine

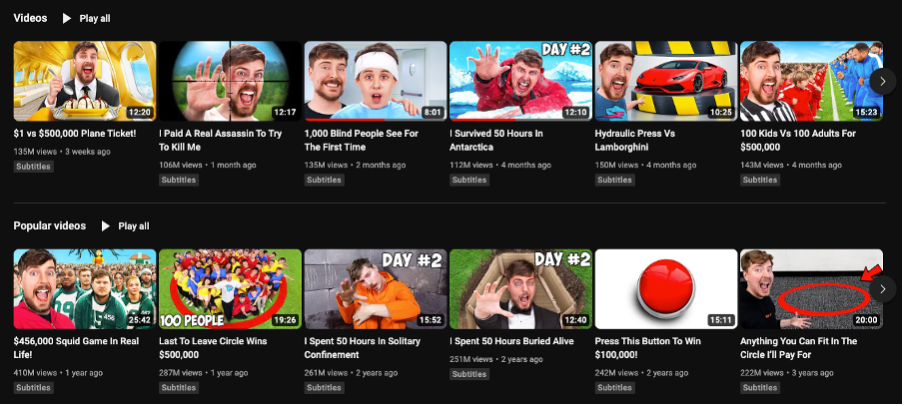

The free thinkers and creators will behave and monetize very differently from the content creators that are wanting to serve their algorithmic masters. And that’s what we’re starting to see. As I mentioned in TMW #123 | The contentification of everything, creators like Mr. Beast are hailed as modern media geniuses for their ability to get tens or hundreds of millions of views consistently on YouTube. But the guy is completely devoid of interests outside of studying and optimizing stuff for the YouTube algorithm. At an early age, he abandoned all other interests and pursuits in life to create on YouTube. And this is why his YouTube channel looks like this:

Despite his huge success in growing his YouTube and then expanding into CPG and food and beverage – and of course his charity project, a miserable content strategy that exploits poor people for views – there’s a certain type of person who likes to consume that content, and it’s not the Einstein’s of the world. Far from it.

MrBeast is the most obvious aspect of this, but there are millions of people who are following his advice on how to create the perfect YouTube Thumbnail, or how to get millions of views. And on other social networks, it seems that for a lot of people, the primary goal of creating content is to increase their follower count.

Viral sensation Andrew Tate learned this early on. He converted his social following into a course that teaches men how to exploit women, which now reaches millions of young people by preaching about the virtues of manhood. I don’t know how his court case, where he’s charged with rape and human trafficking will go, but if he's guilty of one thing, it’s hacking the algorithm for what people want – divisive, coarse, and harmful content.

A little bit closer to home, marketing professor Scott Galloway – known for his forecasts and insights in the marketing world – is increasingly publishing self-help and political commentary in his popular No Mercy No Malice newsletter. A media start-up called Every is doing a similar thing, pivoting from excellent tech analysis to self-help topics. Why? The algorithm loves self-help, advice-based, and emotional content.

And why is that? The easy answer is that most people in the world are struggling, and want answers. One in five people in the US live paycheck to paycheck, and it’s a well-known secret that the entertainment industry exists for the same reason drugs, drinking, and the sex work industry do – to give people an escape from reality. If you’re struggling and facing huge financial, career, or personal difficulties, it’s hard not to escape into the Andrew Tate controversies, or seek life advice from Scott Galloway, of all people.

In entertainment, we’ve seen this with the relentless optimization of cinema. Four of the top ten grossing films are from the Marvel Universe, and five of them are sequels from existing franchises. And then you have guys like Cody Schneider advising marketers to use generative AI to spin up thousands of articles to game SEO. Don’t worry about creating real content, just keep gaming the algorithms until the numbers go up.

What we get when news outlets, creators, movie makers, influencers, and business celebrities create for the algorithm is increasing homogeneity. Everything just becomes less interesting.

Marketers need to stop giving people what they want. It’s wrecking the viability of anything new to enter the mainstream consciousness, and it’s degrading our perception of life and what’s possible. People are turning against these platforms because they want something new, unexpected, and sometimes challenging. Why? Because that stuff is actually interesting.

Cold wars and hot topics

The Cold War between the United States and Russia from 1945 to 1991 was ironically named by George Orwell of all people. It was a “cold” war because it was somewhat of a Nuclear stalemate between two nations. The Cold War was a long period of tension, with some skirmishes here and there, but ultimately ended when Communism was dismantled in Russia.

Today, in a different, digital domain, we’re seeing two powers emerge as the changing landscape of content creation and consumption continues to evolve. And it’s causing all kinds of tensions and conflicts.

As these conflicts start to rise, I think we’ll start to see mainstream media completely exit any sort of dealings with the large tech platforms. The New York Times’ potential legal action against OpenAI is one example here. The Times is not happy for OpenAI to train on its content without renumeration. And for good reason: high-quality content isn’t free, so what gives OpenAI a justification to use that content to create a product people will eventually use for news? Google’s generative AI-powered news platform (currently in private Beta) has already been met with outright rejection from publishers.

After all, if these platforms are increasingly filled with generated nonsense and growth hackers, people will start to make for the exits, and the audiences with the real purchasing power (the smart ones) will leave first. Social media, AI, and search platforms need trusted, reputable and recognized media institutions to stay in the game. But it’s too late; for media, the tech industry has been too extractive and too unforgiving for far too long.

And it’s intensifying in different parts of the world. California has a bill with the Assembly Judiciary Committee to force social media, search, and other internet platforms to pay newsrooms for displaying their content online, saying “newsrooms are coerced to share the content they produce, which tech companies sell advertising against for almost no compensation in return.”

I pointed out a couple of years ago that when this was tried in Australia, it didn’t work. The Australian government was coerced through Facebook’s shutdown of news on its platform and ended up brokering a deal with a small group of the country’s largest news media companies. The same kind of legislation in Canada is facing a huge backlash from big tech firms and the public.

Media, governments, and big tech are in open conflict now for who should own what, what’s considered valuable, and how content can be used for commercial purposes. But the kicker is that these “legacy” media companies have real technological sophistication now. The Times is AB testing everything online just as much as most other big tech platforms.

The ability to build online platforms now is a solved problem, unlike the situation in 2005 when news media was fooled into participating in what would become huge extractive social media and search platforms.

The balance could shift in traditional media’s favor, and we might see these companies exit social and search platforms altogether in favor of better opportunities in their own space and to meet consumer demand for handmade content. The gap is widening between the algorithmic and the genuine. The artificial and the human. The time-worthy and the distracting. And the paywall and the newsfeed.

Out in the cold

Like it or not, media and tech are at odds with each other, but their relationship is symbiotic. They both need each other, but generative AI could become the straw that will break the camel’s back. The advantage in the next decade will be authenticity because misinformation and attention-hacking virality do not lead to long-term growth, learning, or even satisfaction with how we use our time.

Government intervention is also a very real possibility as the problems of algorithmic social are creating for democratic elections and the mental health of our young people are unavoidable. The DOJ lawsuit against Google’s monopolistic advertising ecosystem will be a watershed moment for the industry. Big tech is increasingly constrained in how they can grow, who they can acquire, and how they report data back. The gears are slowly coming to a stop.

Generative AI supercharges this problem as misinformation gets smarter, more targeted, and easier to make. As Toby Walsh, who runs the AI lab at UNSW, explains: the algorithmic content that is cheap and easy to make can fracture our view of the world, screwing up societal cohesion and what we consider to be cultural norms.

With generative AI, this shift may happen faster than we think. The infrastructure of the internet is already built, so there’s little waiting needed here for a new tech paradigm. The cultural change is more important than the technological one because it’s about what people actually value. And the value of algorithmic social is diminishing.

Marketers and people who are invested in building their own audiences should take note. Now is not the time to go all into any social media platform. As Singer helpfully suggests, the ability to export and activate your audience elsewhere will become a big part of who joins which social networks. Owning a first-party data audience is akin to having health insurance; you’ll be screwed one day without it.

“You should be building an audience in a place agnostic of the whims of any one company or entity and using the macro platforms as channels of distribution. And one that lets you export your list (note: the next big social platform, if there ever is another, probably has to let you do this if it wants to get any traction). That is, if you are serious about sharing thoughts online over the long term and not being at the whim of algos, lawyers, big media or committees.”

Going viral on these platforms will become a position of derision instead of virtue, and the value of discovery found in hand-crafted content will become an in-demand rarity.

These are all opportunities for media companies to regain their advantage. We might see the day when Big Tech will be out in the cold huddling over whatever engagement they can farm with the growth hackers, the spammers, and Andrew Tate’s of the world. The content cold war is coming… are you ready for it?

Stay Curious,

Make sense of marketing technology.

Sign up now to get TMW delivered to your inbox every Sunday evening plus an invite to the slack community.

Want to share something interesting or be featured in The Martech Weekly? Drop me a line at juan@themartechweekly.com.