TMW #110 | The day customers stop sharing data

Welcome to The Martech Weekly, where every week I review some of the most interesting ideas, research, and latest news. I look to where the industry is going and what you should be paying attention to.

👋 Get TMW every Sunday

TMW is the fastest and easiest way to stay ahead of the Martech industry. Sign up to get the full version delivered every Sunday for this and every TMW, along with an invite to the TMW community. Learn more here.

George Orwell’s greatest work, 1984, describes a dystopian hellscape where the citizens of London are subjugated to intense control by the government. One of the ways this is done is with the Telescreen, a kind of smart TV hung in every room of a person’s house that watches and listens to everything people do.

In the story, the protagonist, Winston, starts journaling in a notepad (a forbidden activity under the ruthless regime), but he does so in a corner of his living room where the all-seeing eye of the Telescreen can’t see him.

This is a good analogy for a few threads that are coming together in both the Martech and AdTech industries. With third-party cookies deprecating, there’s no singular response to what should come next. But one area that has momentum within the cookie chaos is the growing appetite the programmatic AdTech platforms have for first-party data.

Like the Telescreen of 1984, personal devices have become the all-seeing eye into our lives. But instead of government coercion, people have been happy to part ways with their data in exchange for free services. And the companies that leveraged third-party data have recognized this and are moving into data sources that are even more sensitive, private and personal – first-party data.

And while third-party cookies have to be deprecated, there is a real risk that first-party cookies could go the same way over time. The main reason cookies are going away is because of surveillance. People don’t want their information shared with other parties, and increasingly, the government doesn’t want it either. According to a new case released by the DOJ this week against Google’s monopolistic practices in advertising technology, there is no denying that the AdTech industry needs serious reform.

“As a result of its illegal monopoly, and by its own estimates, Google pockets on average more than 30% of the advertising dollars that flow through its digital advertising technology products; for some transactions and for certain publishers and advertisers, it takes far more. Google’s anticompetitive conduct has suppressed alternative technologies, hindering their adoption by publishers, advertisers, and rivals.”

What’s interesting is that this quote reflects the end outcome for third-party cookies, a technology that was not designed for programmatic advertising, audience sharing, ad personalization and attribution analytics, but was leveraged by companies like Google to build vast troves of customer data. The third-party cookie was the foundation of the modern AdTech ecosystem we have today.

In the past, the DOJ has punished financial monopolies and shady behavior in the broader markets. But data has been harder to pin down. An email address is not a dollar. But it could turn into many dollars if you use the data in the right way. But the framing by the case suggests that data collection will enter the domain of more serious resource management regulation like finance.

With indictments like this against Google, the GDPR’s ongoing fines, and privacy enforcement and big tech making significant adjustments to privacy, all of these changes impact the public’s perception of the data they collect, and people are starting to take notice. As the privacy vice tightens around the AdTech ecosystem, third-party cookies is the first real causality. First-party data is the next port of call. But should it be?

Will first-party data save us?

This leads us to first-party data as the next savior. What’s interesting about the push to move past third-party cookies is that most AdTech vendors are now building platforms to switch to first-party data, including data cleanrooms, CDP offerings and the all-to-familiar and concerning complexity surrounding the way first-party data can be shared and used for advertising.

Over the past two weeks both of the largest advertising technology firms in the world, The Trade Desk and Lotame have released their own version of a CDP geared specifically for the purpose of greater integration of first-party data into various ad networks. This is important because it is a major statement of support for first-party data as the next source of rich advertising fuel for digital marketing.

And there’s been plenty of activity the run-up to this point. For example, the Trade Desk’s UID 2.0, a first-party data solution for tracking is the most widespread and readily adopted option of its kind. According to Digiday, the technology is gaining further support from agencies, and with the backing of The Trade Desk, there’s a good chance that it might emerge as the main solution to replace third-party cookies.

UID2.0 works as an encrypted identity-sharing service across a variety of publishers, which is centrally controlled by The Trade Desk. By adding your email address to a website or app, this can be encrypted, assigned a unique identifier (a UID), and then publishers are able to use that to identify you and your browsing and purchasing history when you sign into other websites.

The problem is that the technology circumvents existing tracking prevention technologies in browsers. According to a 2021 Mozilla analysis of UID2.0, the technology doesn’t really address any of the privacy concerns of previous tracking tech. By sharing encrypted identifiers associated with an email address, users cannot control which websites track them because the data doesn’t live on the browser like a cookie does; it is shared between networks using your email address. Mozilla describes its conclusions like this:

“These proposals depend heavily on policy controls: asking the user for consent before tracking them and then restricting the use of tracking data. However, it is not possible for the user to verify that these policies are being followed and it is unclear whether it will be practical to effectively enforce them. Even if these policies were to be stronger and clearly enforceable, the end result would be a large number of entities possessing user browsing history, which is precisely the situation that browsers are currently trying to address"

The New York Times in a consumer-targeted article tracking the growing privacy risks around sharing an email address describes UID2.0 and its use of email addresses like this:

“First, it helps to know why companies want email addresses. To advertisers, web publishers and app makers, your email is important not just for contacting you. It acts as a digital breadcrumb for companies to link your activity across sites and apps to serve you relevant ads.”

Does this sound familiar? If you’ve worked with third-party cookies, it should.

Without reflecting on what got the advertising ecosystem into this mess in the first place, and doing the hard work of invention to build something else that could satisfy privacy regulators while allowing brands to do targeted ads, this rush by AdTech vendors towards first-party data is concerning.

The sad thing about the depreciation of third-party cookies is that almost every AdTech vendor appears to be shifting to first-party data instead of reflecting on why third-party cookies have to go away in the first place. In the same way that cookies were not fit for advertising purposes (it was a happy accident of invention and opportunity), first-party data seems less fit for the kind of scalability needed for advertising, but also it reveals far more sensitive information about people. A cookie stored on a browser is more about the device than the person, but an email address is a window into an identity.

No soup for you

Unfortunately, there’s no stopping this trend towards first-party data. As first-party data becomes a major force in advertising, and with regulators catching up and becoming more sophisticated in understanding the industry, there’s a big risk here that first-party data will become more than what it should be.

We collect email addresses for important security and legal reasons; we need to contact customers about the products, subscriptions, or services they purchase. We use first-party data with cookies to keep people logged into services or to detect a foreign login. We use it to calculate lifetime value, purchasing propensity, churn risk, and product usage. Without it, the marketing industry would be flying blind.

This is why we need to think about exactly how first-party data should be used in the context of advertising. It’s not like we haven’t been sending Facebook and Google our customer’s email addresses for years anyway. First-party data has a long and well-chronicled history in advertising, but the reality is that its growing role in the AdTech ecosystem will introduce a slew of new issues.

A few of these issues include the way audiences get matched and sent around to various networks. While data clean rooms play an important role to ensure privacy while sharing data, there’s still a mountain of risks. Who’s able to see customer data? How much do you expose to a user? What are the limits? How are users supposed to control this?

The industry barely has a concept for the various states of identity along the advertising supply chain; how can we ever expect consumers to learn what it means to use an encrypted version of your data to send to Amazon or Meta to target you with ads?

If we push our luck with what we can do with first-party data in advertising, we might just end up like George Costanza: denied the right to use first-party data for advertising by government regulators, Big Tech platforms, or by the customers themselves. No soup for you!

What do consumers want?

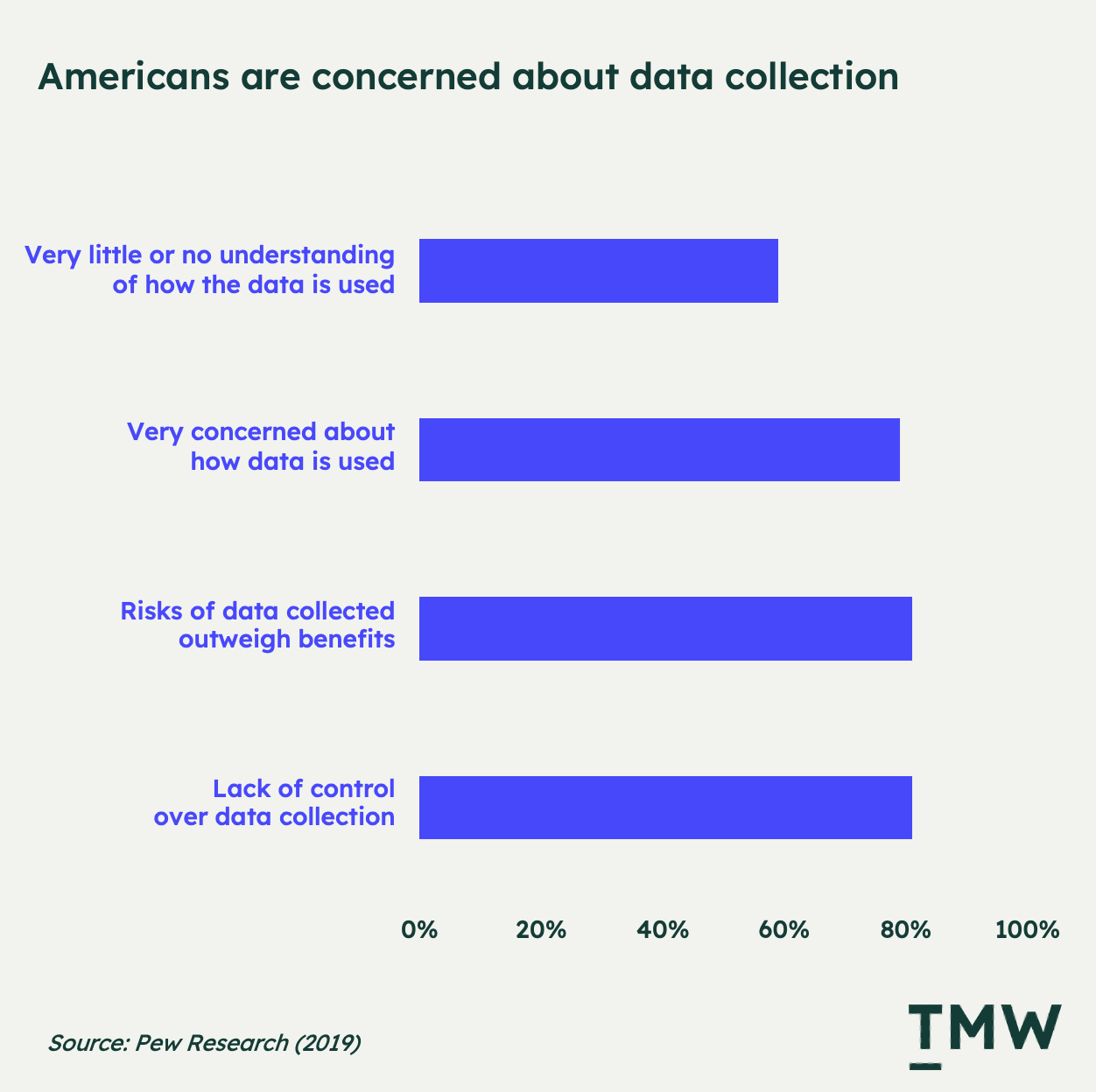

The real question here is whether the average person actually cares about data privacy in their own lives. Apple’s ATT prompt, which functions as a kind of survey-in-production for what people do when confronted with a decision to be tracked in-app, is overwhelmingly against it.

In the United States the concerns around data privacy is growing, but US consumers are signing up for apps like TikTok in droves, which has been flagged as a Chinese surveillance risk. Overall, the picture is mixed, but definitely trending toward greater regulation, and controls for consumers.

But in other parts of the world, consumers are willing to take on more responsibility for their data. A new research survey in Singapore suggests that the majority of citizens want full control over their data and how it’s used. Beyond sharing their preferences with a brand, they want to see and control everything’s that’s tracked about them.

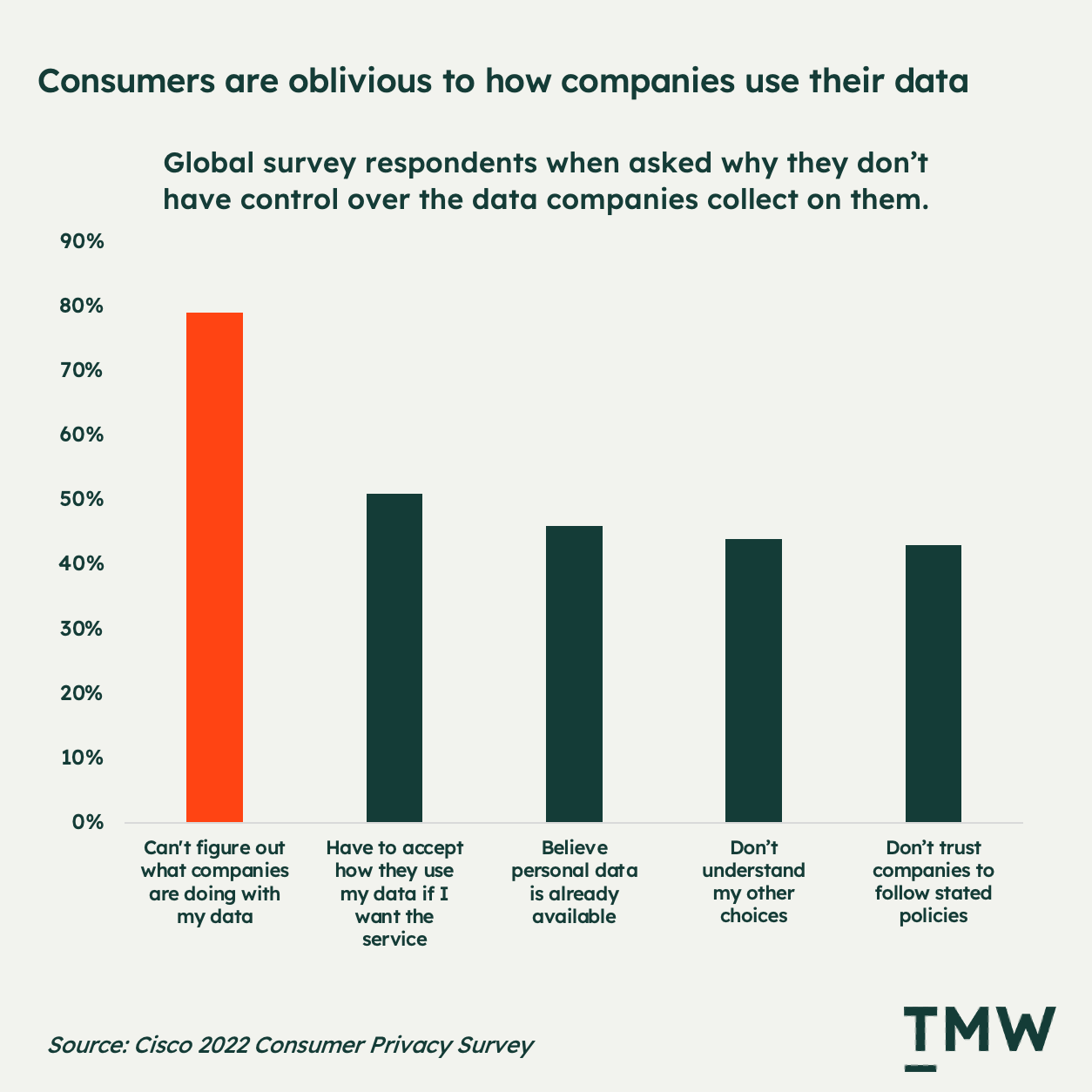

From a global perspective, only 23% of consumers feel like they have control over their personal information online. And according to a 2022 Cisco report, for those who don’t have control over their data, a staggering 80% of them said the reason why was due to not being able to figure out what companies are doing with their data. I think we have a communication problem here.

Even Google cites the growing demand from users for a more private web when they announced the first step to remove third-party cookies from Chrome:

“Users are demanding greater privacy – including transparency, choice and control over how their data is used – and it’s clear the web ecosystem needs to evolve to meet these increasing demands. Some browsers have reacted to these concerns by blocking third-party cookies, but we believe this has unintended consequences that can negatively impact both users and the web ecosystem.”

Right now, people exchange their information for free things on the internet. That exchange has worked quite well, so well that it has brought a significant amount of innovation into the industry. The consumer doesn’t see what happens with their raw information – how it’s pushed and pulled around the web to deliver a personalized ad to you. And in a lot of ways that doesn’t really matter. Living online is living with ads. That’s not going away.

Yet, we don’t ask people for their email address or phone number to access a store (unless you're Costco), get a haircut, or visit a restaurant. Because the online domain skews behavior in significant ways, it makes asking for personally identifiable information commonplace.

If the trend continues and first-party data like email addresses become the core tracking identity, the rate of marketers asking for email addresses goes up, along with an increased demand for personally revealing data. Increasing your information ask is going to be more detrimental to the customer experience. Do we really want this for the web?

Nowhere else to go

The rush of advertising behemoths, data infrastructure companies and marketing suits “solving” the third-party cookie problem by just using first-party data is only going to create more problems. The data is nowhere near fit for purpose, and despite the needs of marketers to do targeted advertising, the real question is how much you’re willing to risk: one bad actor, one glitched encryption protocol, or one nosey journalist could tear the promise of first-party powered advertising to the ground.

And if that happens, then what?

We are custodians of customer data, and so knowing the limits for your brand goes beyond what we just do operationally. Marketers need to decide where they stand, but I’m sure the tide of competitors leveraging first-party data for advertising to grow their companies will make the decision for them.

First-party data is already the defacto solution to a third-party cookieless internet. But all I’m asking for us to do is use our imaginations a little more.

If first-party cookies, email addresses, unique identifiers, and other subtypes of first-party data become the bedrock for another kind of internet monopoly like Google, then we literally have nothing left to lean on to make data-driven marketing work. Customers may pull back or only trust a small number of giant companies like Apple or Amazon with their data, leaving everyone else out in the cold.

Marketers should be working on their brands. Have the best website on the internet, ads that blow people’s minds, recruiting advocates that instill trust and products that people love. That’s the best cure for a cookieless web, not maligning first-party data into something it was never designed to support. Jackie Yeaney, the Chief Marketing Officer at Tableau, said it well:

“When I started my career in marketing, I believed that data and logic would provide the answers. After all, I was an engineer. Then I built teams full of creative souls and leaned into ideas that I never in a million years would have come up with myself. It turns out that the best marketing happens at the intersections of data analytics and creativity. And neither of those things require third-party tracking.“

Of course, if we can’t find a suitable replacement for third-party cookies, this leads to an internet with generic billboards, where nothing is personalized and only the privileged few get to send you something relevant. This is the Orwellian option, but a very real one.

No data means no personalization for both advertising and owned channels. I think one thing that consumers and marketers can agree on is that we both want that – relevancy is a real thing that people rely on all the time. That’s one of the reasons why we can’t stop scrolling social media; it saves us time and offers us things that we’re really interested in.

But the reality is that customers will trust brands less if there is a public perception that sharing your information could be a risk to safety or an easy road to online surveillance. When Winston from 1984 is writing in the corner of his flat, out of the ire of the Telescreen, what he’s expressing is a desire for privacy. It’s a desire we all share.

As the AdTech giants continue making progress with first-party data solutions, this might be the thing that tips the scales toward a skeptical and reserved public that no longer wants brands to know anything about them.

The risk is that as we continue down the path of maligning first-party data for the purposes of targeted advertising, we may soon see the day when customers stop sharing data with brands altogether. If we can no longer be trusted as custodians of the cookie, what makes us think that we’ll do any better with an email address?

Stay Curious,

Make sense of marketing technology.

Sign up now to get TMW delivered to your inbox every Sunday evening plus an invite to the slack community.

Want to share something interesting or be featured in The Martech Weekly? Drop me a line at juan@themartechweekly.com.