TMW #128 | The grifterverse

Welcome to The Martech Weekly, where every week I review some of the most interesting ideas, research, and latest news. I look to where the industry is going and what you should be paying attention to.

👋 Get TMW every Sunday

TMW is the fastest and easiest way to stay ahead of the Martech industry. Sign up to get the full version delivered every Sunday for this and every TMW, along with an invite to the TMW community. Learn more here.

Some news: I’ll be speaking at Mops-Apalooza by Marketingops.com in Anaheim, California this November. It will be a little different from my usual talks - I’ll be unveiling the results of a new TMW product I’m working on that launches in a couple of weeks. Check out the event here.

The grifterverse

The idea of the grifter is more than 100 years old. The Columbia Journalism Review defines it as a person who relies on sophisticated skills to fool people out of their money as opposed to committing acts of violence. The grifterverse is a way to describe a commonality across Web3, crypto, metaverse, generative AI, and the influencers selling courses on how to use these technologies: the endless pushing of novelty for commercial gain through deception.

And it’s becoming a big problem. The FTC estimates that US consumers lost nearly $8.8 billion in scams in 2022, with an increase of 30% since 2021. About half of the money lost to scams was through deceptive investment schemes. What happens when internet grifters are left unchecked is the web becomes increasingly unusable as people trust what they are seeing online less and less to protect themselves.

A big part of the online grift is the highjacking of trends. I defined some of this in TMW #117 | A hypothesis for hype, that reframes how we should understand tech trends. In it, I argued that hype is speeding up, and instead of it petering out to an eventual adoption by consumers, the most recent trends actually go nowhere – just a junk pile of useless ideas, wasted effort, and tech that sits on the shelf. Instead of a cycle, it’s a downward spiral. Remember the Metaverse?

This essay is a sister piece to that essay, looking at the underbelly of hype – the fast-organizing community of trend pushers, thread writers, course sellers, build-in-public-ers, get-rich-quick schemers, and solopreneurs that manipulate social algorithms, promise us the world, position themselves as experts in brand new tech, and ultimately fail to deliver anything of real value and purpose.

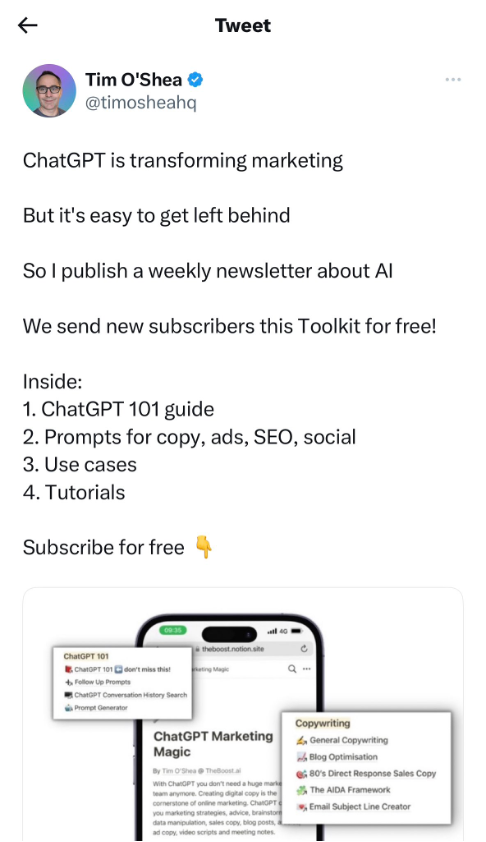

This week has seen the hilarious rollout of Adobe’s Photoshop generative AI fill which online personalities have wasted no time using it to turn famous artwork into gym selfies, and filling out the background of famous album covers. And right in the middle, there’s this subculture, particularly on Twitter, of people who endlessly push this kind of content as ways to get rich, become successful, and who are ready to sell you a course so you won’t be “left behind.”

Web3 had the same undercurrent of people promising a new decentralized future where people could unbank themselves, be paid for the content they create, and find meaning in the community, which ultimately became a giant scam.

A recent article from Reddit’s head of global foresight comments on the lack of meaning in recent trends. Saying that most trends are often ignored – and increasingly so as they have a shorter lifespan – becoming more ephemeral and just plain weirder:

“About 64% of people feel the pace of culture accelerating. We’re seeing trends go meta with anti-trend trends and #corecore—a movement addressing context collapse and the absurdity of life online. It feels impossible to keep up. And the “trends” are inherently fleeting. Ephemerality has a notoriously low ROI, so why should we care about something that will fade?”

I think what’s happening here is that trends used to reflect what everyone was interested in during a span of time. But now there’s an entire economy built around the pushing and promoting of internet trends to make fast money online. That’s what we’re seeing currently with Generative AI, the sheer amount of people saying that you’ll be left behind if you don’t read their thread on 10 game-changing new innovations is mind-boggling.

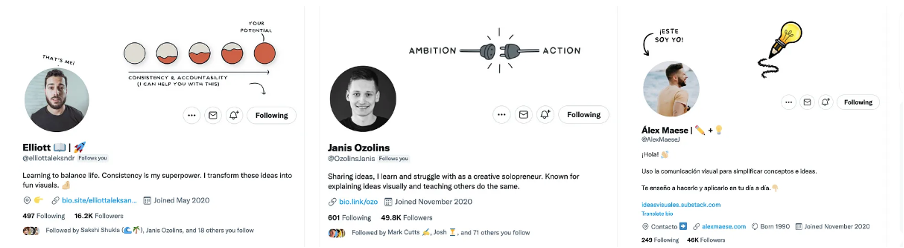

Here’s an example:

This essay is a coalface look at this shady underbelly of internet hype and the people that are building careers as online grifters. Let’s dive into the grifterverse and see what we can find.

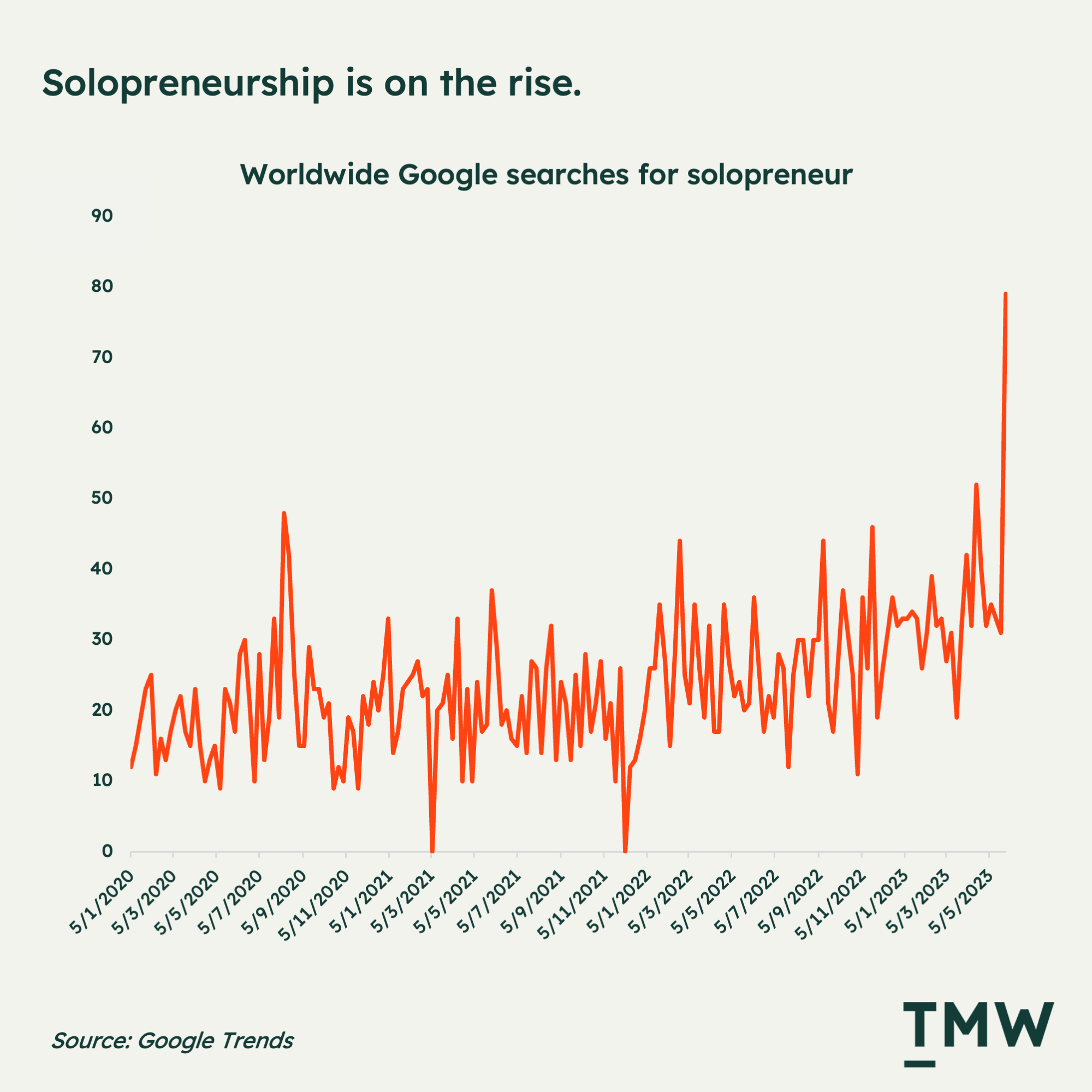

The rise of the solopreneur

Over time I’ve seen a growing cohort of people across social media engage with something called “solopreneurship”, led by internet influencers like Jack Butcher, David Perell, Justin Welsh and Daniel Vassallo, and many others. It’s a topic that seems to be on the rise as these people amass huge audiences of people, but it’s also a good starting point to understand the incentives for online grifters.

These influencers all sell courses with fanciful names like “the solopreneur’s operating system”; “the permissionless apprentice”; and the “write of passage.” All of these courses are digital products that promise to make you just as successful as these wealthy, influential, and in-demand internet celebrities.

I’ve been trying to figure out why these trends grate on me, and I think I found an answer with an interaction with marketing influencer Katelyn Bourgoin on internet grifters this week. In the thread, entrepreneur Zach Weismann posted an article analyzing some of these internet personalities and their selective approach to talking about their success online, where he concludes:

“The work of the influencer is narcissistic, rooted in self-promotion, addictive, dangerous, lacks in credibility or expertise, and further perpetuates a world of the haves and the have-nots — you either have a large following online or you don’t. You either do it this way and be successful like me, or you don’t.”

So here’s the problem with solopreneurship: All of this constant social media posting, audience-building rhetoric, and trend pushing is just a gigantic waste of human talent, capital and potential. Some of it is brilliant marketing, some of it is tapping into human psychological vulnerabilities, and some of it is just straight-up scams.

Somehow the grifterverse sucks people in on the promise that by creating content and following the right trends, you can divorce your time from money and become an accomplished founder, you just need the right framework and education, leverage generative AI, invest in the right useless crypto token or “productize yourself”.

Whatever works

The commonality across the grifterverse is that there’s always a trigger. Usually, it’s a tech trend like the price of Bitcoin growing, Wall Street Bets organizing around Gamestop or ChatGPT’s launch. But it can also be someone finding success in a specific tactic to make money online and telling everyone ad nauseam about their great new hack.

Both patterns have their own kinds of viral dynamics. The thing that makes these kinds of trends so popular is the proof (as far as it is actual proof) that hustling, posting content, and building an audience “works.”

The thing that influencers are usually citing as proof is revenue growth, followed closely by gaining followers, or newsletter subscribers. What litters the social media space of these influencers are screenshots of revenue dashboards, charts going up and to the right, and big recurring revenue numbers. It’s kind of like a never-ending parade of growth. Yet some of the smarter influencers in this space show their progress not with hard metrics, but with the lifestyle they can afford to create with their riches.

Let’s examine Justin Welsh’s constant tweeting about how great solopreneur life is. His message is that he can make $2 million a year as a single-person business through automating tools, writing Twitter and LinkedIn posts, optimizing his “operating system” course for posting content online, and coaching people. When asked what his life’s philosophy is, Welsh replies: “To do what I want, when I want, with whomever I want.” Which is about as deep as a 13-year-old arguing with their parents.

I don’t usually like to signal out specific people on TMW. But this person’s approach is the most illustrative of a particular worldview and value proposition to describe the grifterverse. You could also say that crypto millionaires with their sports cars or shady Twitter scammers with NFT profile pics would be better suited, but those are easy-to-identify scams, and there’s already plenty of analysis about how these get-rich-quick schemes work.

What Welsh and similar influencers represent is a more sophisticated kind of grift. His ideas are popular, have spread, and on paper he is successful in building a large audience of people who want that same thing, because according to him, his content operating system actually “works.” But does it really?

‘Whatever works’ is a shallow way of thinking about creative output online and the kinds of companies that you might want to build. But for those who are seeking fast results and optimizing for a specific revenue goal in isolation, if a certain kind of social post works, it works – keep doing it. If a kind of specific message works, then keep doing it. And this is part of what I call the “contentification of everything”, which turns human creative output into a never-ending quest to please social algorithms:

“This is the cultural shift that is transforming how brands and marketers think about creativity in the constant effort for human attention and relevance. What MrBeast, Mulvaney, and others are teaching us is that genuine creativity doesn’t matter. Just feed the algorithm and appeal to our lizard brains – the seat of our emotions and impulses. The flattening of a wide variety of creative expressions into content on the internet also flattened our ability to appreciate it. Everything looks the same in the scroll.”

The answer to “whatever works” is based on your goals. One easy tell with people selling audience building, coaching, or generative AI courses is that they will point to their follower count, their impressions, and revenue as proof that what they are doing is driving growth and progress – but those things can be easily spoofed. The question we must ask to these kinds of influencers is why they feel the need to work so hard to sell online courses if they are already so successful. The answer is that they aren’t.

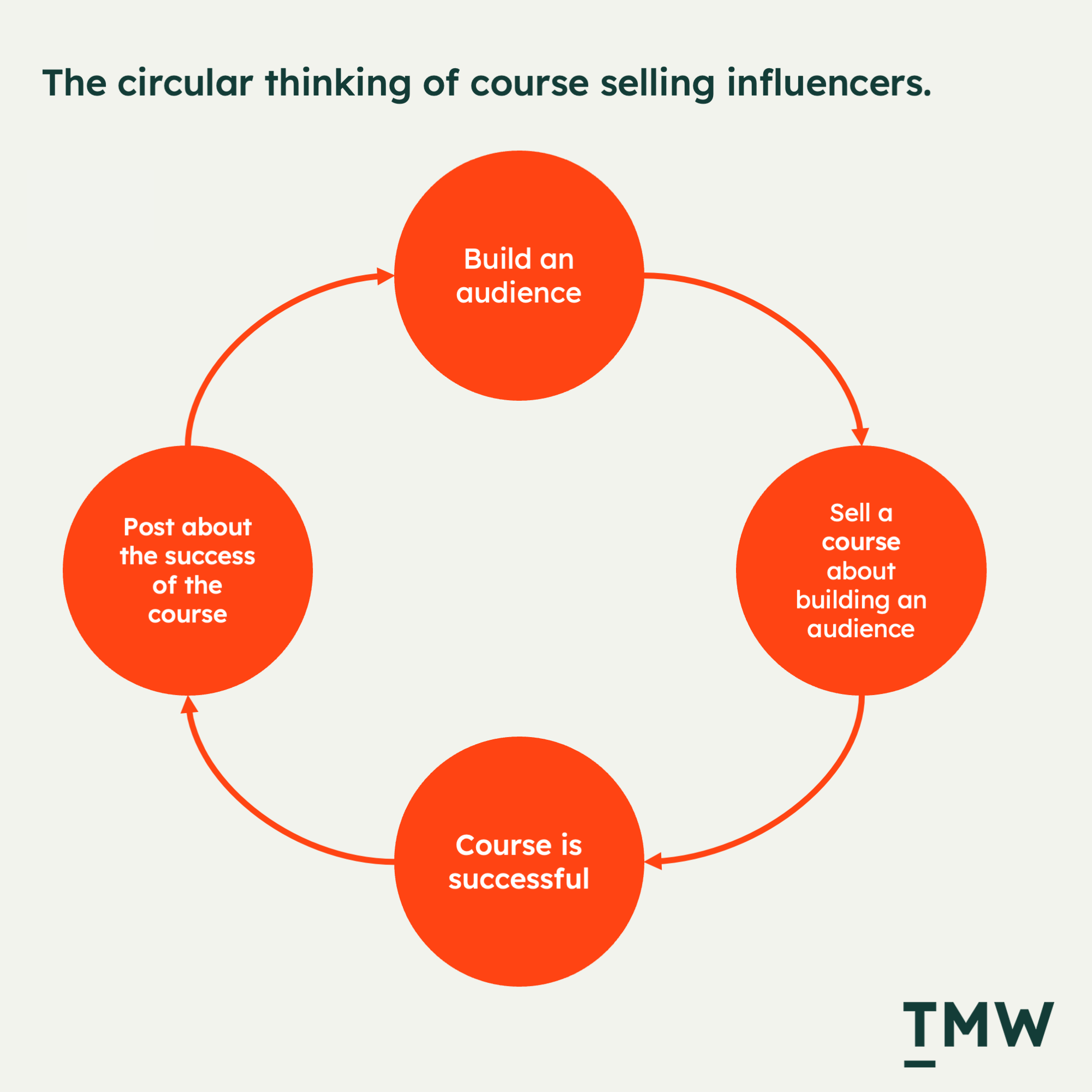

The grift is intentional; the only way to sell a course about building an audience is to prove that you can do it yourself, which then becomes a vicious cycle of selling the promise of audience building by building an audience around your content about building an audience. It’s almost as empty as investing in crypto – there’s no real asset underlying a token, just empty speculation and the greater fool that will buy it for more.

The guy in the hole

The grifterverse is gaining traction because some audiences are easier to build than others. What I mean by this is that there are disproportionally more poor people than wealthy and successful people in the world. There are far more employees stuck in dead-end jobs than company founders with capital, time and resources. When we think about what attracts people to the grifterverse, it’s usually in response to seeking solutions to alleviate financial, time, or relationship poverty.

Building an audience with an attractive promise to escape any one of these states of poverty leads to a specific group of people gravitating to influential people who can teach them how to escape. This is what I call the “guy in the hole” theory.

The idea is a worldview that says that each person is stuck in a hole. It might be a family hole, or a disability hole, or financial hole, or a dead-end career hole. And the theory goes that getting out of this hole is what most people are working towards. In the United States alone, 11.6% of the population — 37.9 million people — were in poverty as of 2021. And so there are a lot of people that are desperate for solutions to escape that poverty, and these people are plentiful across free social media networks.

Like the infomercials and multi-level marketing schemes of old, there’s really nothing new here when looking at the grifterverse. It’s just the same underlying principle – build an audience of people by promising that by following their advice they can escape a specific hole. Bonus points if you’ve climbed out yourself. All you need is a framework, maybe some coaching and a $199 course, and you too can escape suffering.

What ends up happening is that these audiences degrade quickly over time, either through disillusionment with products and promises that don’t work or by finding other ways of escaping their predicament. Either way, there’s no staying power in building an audience around a promise of escaping poverty or suffering. At worst, presenting information products to desperate audiences just takes more money from people who need it.

Change your words, change your world

In this exceptionally good video series, there’s something incredibly powerful about the flip side of the grifterverse. Larry McEnerney shows us that instead of seeing content as a means by which influencers can advertise products, sell courses or convince people to buy worthless crypto, content can hold value in intrinsic ways.

In fact, I can’t think of a better piece of content that encapsulates my thesis for TMW – that the content itself has intrinsic value – because content information can help people see the world differently. And that change of worldview can unlock growth, opportunity, and yes, the power to “get out of the hole” too. But the value is intrinsic – genuine online writing is about trying to understand the world yourself, and that writing creates thinking and you get to share that with others.

Even David Perell gets this idea half right when asking people to take his course on writing online, but focuses far too much on encouraging people to become what he calls a “personal monopoly”. His idea is that you should use writing to build a differentiated product online that uniquely reflects your style, tastes and interests, not exactly the most virtuous of incentives to share your writing with people online:

Your Personal Monopoly should reflect your innate interests, not what you think the world wants. There are two reasons why: (1) the Internet creates power law outcomes so if you’re not fascinated by what you’re writing about, you won’t be world-class at it, and (2) due to the immense scale of the Internet, the audience for almost every topic numbers in the thousands. If you’re chasing a trend, you’ve already lost.

His overarching point is that there’s something thrilling when someone’s understanding of a tech category completely changes, or their career aspirations take a new path after consuming your content. It’s because you’re thinking influences their thinking. And writing is thinking.

This is what the grifterverse community is entirely missing in producing online content: it’s about helping people at scale by understanding the world in new ways. Reducing content creation into a circular process to sell courses, coaching or ads ends up with a lot of repetition, low creativity, and increasingly deceptive and manipulative tactics to motivate more people to join the grift.

Twitter is the problem

I think Twitter is the main driver of a lot of this kind of discourse around getting rich quickly. The fast feedback loop, the professional community around it, and the tech culture all lean into the grifterverse heavily. It’s also one of the platforms that rely heavily on outrage, ingroup thinking, and polarization. A perfect environment for those trying to build an audience of desperate people with wild promises of freedom and wealth.

What this does is create is a subculture of copycats: people following the advice, using the influencer’s templates, and remaking their personality so that they too can become solopreneurs, as Zach Weismann hilariously points out with a few illuminating examples of people who blindly follow these entrepreneurs:

It’s interesting that while Facebook is optimized for friendship circles and friends, Instagram and TikTok on a specific style of visually immersive expression, and LinkedIn is straight-up self-promotion, Twitter is really the only mainstream social network optimizing on social discourse. In other words, Twitter is the closest thing we have to the streets.

And the streets are a good metaphor for Twitter. The social network amplifies the grifters and the professionals, the political and the violent, the endearing with the obnoxious. All of it is forced into a uniform experience, and personally, I think it’s driving us all a little mad. Like the street performers of Barcelona’s La Rambla, it’s the domain of the general public, and there’s no shortage of people seeking a quick buck in exchange for a magic trick, a selfie, or a handmade trinket.

This is why I think this phenomenon is symptomatic of a larger shift to late-stage social media, where the incentives of posting content online become degraded slowly over time, which tends to bring in more scammers and unethical influencers. As social networks juice our attention for advertising dollars, the way we use social platforms becomes more desperate, this creates optimal conditions for people who can hijack algorithms to keep the grifts going.

It's grifters all the way down

The problem of the grifterverse is impossible to avoid. There are always going to be people selling courses on how to sell courses. There are always going to be people portraying a lifestyle and a framework so you too can escape suffering. My goal with this essay is to educate on a trend that’s pulling people in on false promises with the ultimate outcome of wasted time, energy, and money on something that doesn’t matter. It warrants a cultural analysis.

The ultimate irony of the grifterverse is that a lot of these influencers once did something valuable for society. Justin Welsh worked at a health tech company, and Jack Butcher was a designer at a great marketing agency. For the life of me, I can’t figure out why they’d want to swap careers that create real value for selling courses on how to sell courses.

And this is the sad thing: in the grifterverse, cash is king and personal autonomy is the highest virtue. It’s a small, selfish, and ultimately greedy way to think about the purpose and value of the Internet.

This is the trap that so many people fall into – thinking that careers are about our own personal accumulation of prestige, money and “freedom” – when in reality, our careers should be about serving other people. If anything, I hope my exploration into the grifterverse here inspires you to do more than sell online courses about building an audience on Twitter.

Stay Curious,

Make sense of marketing technology.

Sign up now to get TMW delivered to your inbox every Sunday evening plus an invite to the slack community.

Want to share something interesting or be featured in The Martech Weekly? Drop me a line at juan@themartechweekly.com.